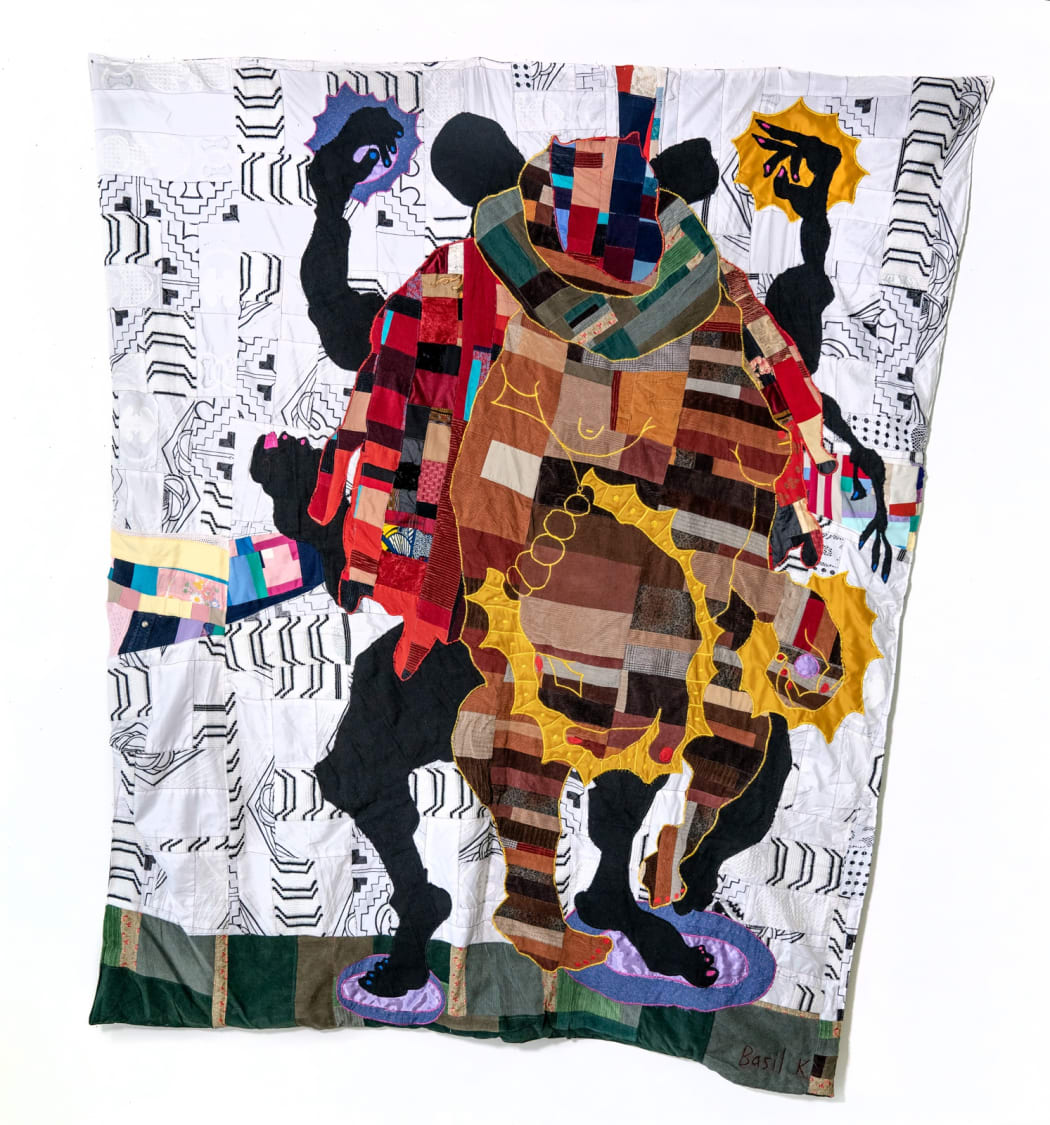

Featured Image: Basil Kincaid, Order My Steps, 2020, Quilt vintage corduroy, donated clothes, clothes from the artist, Ghanaian embroidered fabrics, hand-woven Ghanaian kente, wax block print cotton fabric, and wool, 96 x 85 x 1 in. (Image courtesy the artist and Kavi Gupta.)

By Phillip Barcio

St. Louis-based artist Basil Kincaid is known for creating dramatic, colorful quilts, using a mixture of found and donated fabrics. Yet, the methods and techniques of quilting are relatively new additions to his studio practice—a practice originally grounded in drawing and collage. In 2016, after he returned from a residency in Ghana, a vivid dream in which he was visited by a deceased ancestor put him on a new aesthetic path.

“I dreamt that my grandmother was standing in front of this house—it was one of the St. Louis row houses—and the house was wrapped in a quilt,” says Kincaid. “She was standing on the porch and her aura, her golden light, was pouring out over me. A wave of the energy hit me so hard that I woke up, and knew I had to be making quilts.”

Despite having no experience with the medium, Kincaid nonetheless began accumulating secondhand and donated fabrics, and taught himself the essentials of the craft. His earliest fabric works were abstract, loosely hanging, organic configurations, embedded with the material histories of the fabrics. Creating the abstract quilts brought Kincaid some measure of inner harmony, but then a chance suggestion from his mother led him to embrace yet another evolution.

“My mom has been suggesting ideas for art to me since I was a kid,” says Kincaid. “Most of the time I haven’t taken them, but this time she asked why I wasn't integrating drawing and collage into my quilting, and I could see it in my mind. It just made sense. So I decided to test it out and see where the experiment leads.”

Kincaid started collaging elements of his past quilts together to create new compositions, then taught himself embroidery, which he uses to introduce figurative elements into the work. The first new figurative quilt he made was a tribute to his mother.

“It’s called My Mom’s Prayers Worked,” says Kincaid. “She likes to dance and she likes to pray, and those things have cloaked me. When you look at the piece, one figure has their hands outstretched glowing energy over the other figure.”

Kincaid also finds inspiration in the space where his personal history intersects with the broader history of his various communities, including the larger African American community, the community he has become part of on his trips to live and work in Ghana, and especially the church.

Raised in the Christian tradition with a father who was a preacher, Kincaid has thought a lot about how slaves from Africa were forced to adopt Christian practices and beliefs, but then how they integrated aspects of this new faith with their existing belief systems to create a living, and completely unique spiritual tradition.

“In these new works I introduce religious iconography," says Kincaid, "and the titles reference different negro spirituals. I’m looking at how Christianity services and disservices Black people, and relates to both liberation and shame.”

One piece called Riverside Revival, Lift Every Voice and Sing is made from old choir robes from a church in St. Louis.

“The materials, if you can decode them, will tell you a story," says Kincaid. "Like messages hidden in the quilts in underground railroad times, depending on how close you are, you may have different levels of access to the work.”

Other topics Kincaid is addressing in the work include rest and dream life. A quilt titled Lullaby shows one figure resting, while a second, mysterious black figure takes a protective stance over them.

“This image is connected to the concept of rest as a revolutionary activity,” says Kincaid. “One of the most consistent practices of slavery, which we now self-inflict, is sleep deprivation. They’d work you all day and terrorize you through the night. Taking the liberty to rest is deeply connected to happiness, and essential to personal freedom.”

Another key work, Order My Steps, references memories Kincaid has of his mother singing hymns while his father, a preacher, got ready to preach. Around the hands and the feet of the figures in the image are circular forms, reminiscent of paths the figures are walking on, and the energy of the actions they are taking.

“Order My Steps was one of the songs she would most commonly sing,” says Kincaid. “The song is about trusting the calling of your life. I knew art was choosing me even back then, but it wasn’t easy to choose back. Something inside of me said keep going even though it may not make sense right now. This piece is about trusting your intuition.”

Throughout time, tapestries have been used to tell stories of what was happening. Kincaid's quilts map the very personal journey Kincaid is on. They also tell a story of the expanding liberation of all the people who share his various communities. Kincaid’s repeated trips to Ghana in recent years have especcially brought him new insights into what he calls “a gradient sensation of belonging.”

“When I go back to Africa, I’m supposed to automatically belong. Yes there’s a connection, but the place my ancestors left and the people they left and were taken from no longer exist,” says Kincaid. “What you notice about Black people in the United States is that we really are indigenous to ourselves. We’re apart form both places but somehow still entirely our own.”

Kincaid paraphrases a James Baldwin quote: “A place where you will belong won’t exist until you create it.” His new body of quilts is about creating that place.

Phillip Barcio is the Communications Manager and Associate Director for Kavi Gupta.