SIX INTERNATIONAL WOMEN ARTISTS CONGREGATE IN THE HAMPTONS' PARRISH ART MUSEUM

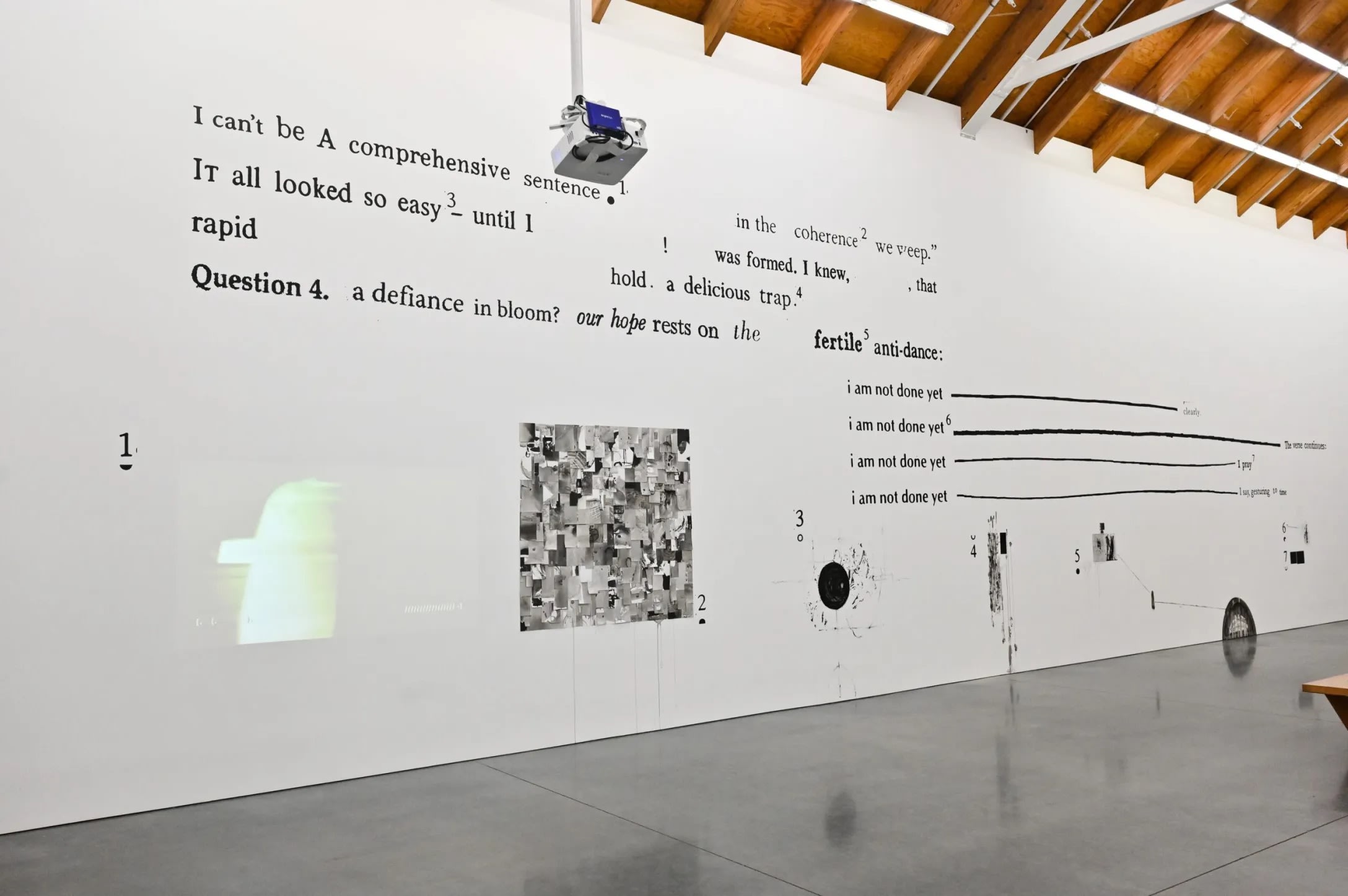

The phrase “set it off” has two interpretations: to do something intensely in a major way or to interrupt and alter the status quo. In the Hamptons, the Parrish Art Museum‘s group exhibit of the same name realizes this idiom’s definition to its fullest extent. Put together by curator Racquel Chevremont and beloved artist Mickalene Thomas, collectively known as Deux Femmes Noires, Set It Off features over 50 artworks from six artists: Leilah Babirye, Torkwase Dyson, February James, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Karyn Olivier and Kennedy Yanko. By boldly engaging history, identity and different artistic mediums, these artists create a varied, bold show (open now until 24 July) that is profound in its concept as well as its execution.

When conceptualizing the exhibit, Chevremont and Thomas sought an international selection of women artists, whose works avoids and disrupts convention. “For Set It Off we wanted to bring together a group of women who work in a range of media and styles and whose subject matter spans the personal, historical and cultural,” the duo explains. “Each was chosen for their unique artistic language, for forging their own path and creating work that transcends traditional, formal and art historical structures. These artists have distinct styles that completely set them apart within the art world.”

February James is one such artist. Known for her ethereal watercolor portraits of Black people, James presents “These Are My Ghosts To Sit With,” a multi-part installation that combines a portraiture series with a cardboard installation of a living room. Her hazy, smudged paintings capture subjects as if through a memory or dream, casting each subject in a complex range of expressions. When hung around the cardboard installation, the portraits seem to haunt the unoccupied room, meditating on the relationship between people and objects; Black identity and community. “The use of cardboard reinforces the need to ‘make do’ with what we have and embodies the fragility and temporality of individual reality,” the artist explains. “Within a blink of an eye the entire thing can be damaged, destroyed or no longer here.”

While James reframes objects to interrogate the collective’s relation to the personal, Karyn Olivier situates objects in their political and environmental context. For the exhibit, she presents a series of photographic prints encased in asphalt or roofing tar, as well as the large-scale sculpture “How Many Ways You Can Disappear” (2021). The foreboding title gives way to 13 feet of salt-casted pot warp (lobster fishing rope) recovered from Matinicus Isle in Maine. The rope is tangled underneath fluorescent green, blue and pink marbled buoys that hang from a clean white rope. Here, the limp, functionless rope bring its salt remnants to the forefront. “I was thinking of salt’s history in relation to trade/currency, particularly the practice of trading slaves for salt in Ancient Greece,” says Olivier. In depicting everyday objects as what is left of them, the artists analyzes how history is distorted, forgotten and retold to fit personal narratives.

Leilah Babirye’s sculptures, composed of trash collected from the streets of New York, address issues of sexuality, identity and human rights. The artist, who was born and raised in Kampala, Uganda, tells COOL HUNTING, “I was finding beauty in found materials. The use of trash is intentional—the pejorative for a gay person in Luganda is ‘ebisiyaga’ which means sugarcane husk. It’s rubbish, the part of the sugarcane you throw out. The bicycle chains and aluminum cans refer to my first years in New York as an asylum-seeker collecting cans and working as a bike messenger. I use them to embellish my sculptures.” Reclaiming the slur, Babirye transforms trash into majestic, regal figures.

One sculpture in particular, “Tuli Mukwano (We Are in Love)” (2018), imagines an alternative reality where queer love is celebrated. The sculpture depicts two abstract figures (made from carved wood reminiscent of traditional African masks) caught in a lover’s embrace and adorned with headdresses. One crown-like piece is made from woven Sprite, Pepsi and Schweppes package wrappers and the other is crafted from soda and food can tops, chicken wire and found metal.

The artwork evokes “kuchu,” which, the artist continues, is “a ‘secret word’ of Swahili origin that those in the queer and trans community use to address each other.” Through carving, painting and ceramic making, Babirye crafts her own kuchu community. She tells us, “I also choose to affix the names in the titles of my works with the feminizing prefix ‘Na,’ queering the culture in which I was raised; questioning gender and power. The sculptures become stand-ins for the many transgender women, whom we refer to as queens in the ‘kuchu’ community who often name themselves after their favorite aunts, sisters or women role models.”

Across expansive work of surprising and unexpected materials, the six artists in Set If Off innovate various mediums to fortify and relay their poignant messages. Ruminating on the narratives that are personal, shared or contested between them, the artworks come together for a powerful examination of art and the world at large.