Chicago, a skyscraper city with an adventurous musical ear and love affair with South African jazz, has in recent years become an important staging post for new art being incubated in Cape Town.

Much of the activity has been concentrated in the rectilinear exhibition halls of the Renzo Piano-designed Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago, which is currently hosting a solo exhibition by Igshaan Adams.

Desire Lines is Adams’ first major solo presentation in the United States, and gathers 20 textile pieces, most of them weavings composed of various beads, shells, baubles and rope, created between 2014 and 2022. It is a poised debut, one that also cuts across a dominant art world trend to offer figure paintings as wound dressing in the wake of Black Lives Matter.

His exhibition also follows institutional firsts at the same venue by two of Adams’ contemporaries from Cape Town. In 2016, Kemang Wa Lehulere presented All My Wildest Dreams, a magical assembly of chalk and paper drawings, sculpture, video and various tchotchkes (including ceramic dogs and a stuffed parrot). The fussy New York Times travelled west and hailed Lehulere “a rising art star”.

Two years later, in 2018, James Webb made his US debut with a sonic portrait of Chicago’s various religious communities. Webb’s multichannel sound installation Prayer (Chicago) combines 240 recordings of prayer and vocal worship by Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Judaic and Muslim congregants from the Chicago area.

Although part of a larger project started in 2000, Webb’s Chicago work remains the most ambitious example of his fieldwork to date.

Space and a network of patrons help explain this legacy museum’s ambitious programme. Located opposite Millennium Park, a green lung near Lake Michigan crowded with ritzy architecture and public art, the institute is the second-largest art museum in the US.

Its collection of 300 000 works spans various epochs and media. Contemporary South African artists represented in the collection include Marlene Dumas, William Kentridge, Sabelo Mlangeni and Zanele Muholi.

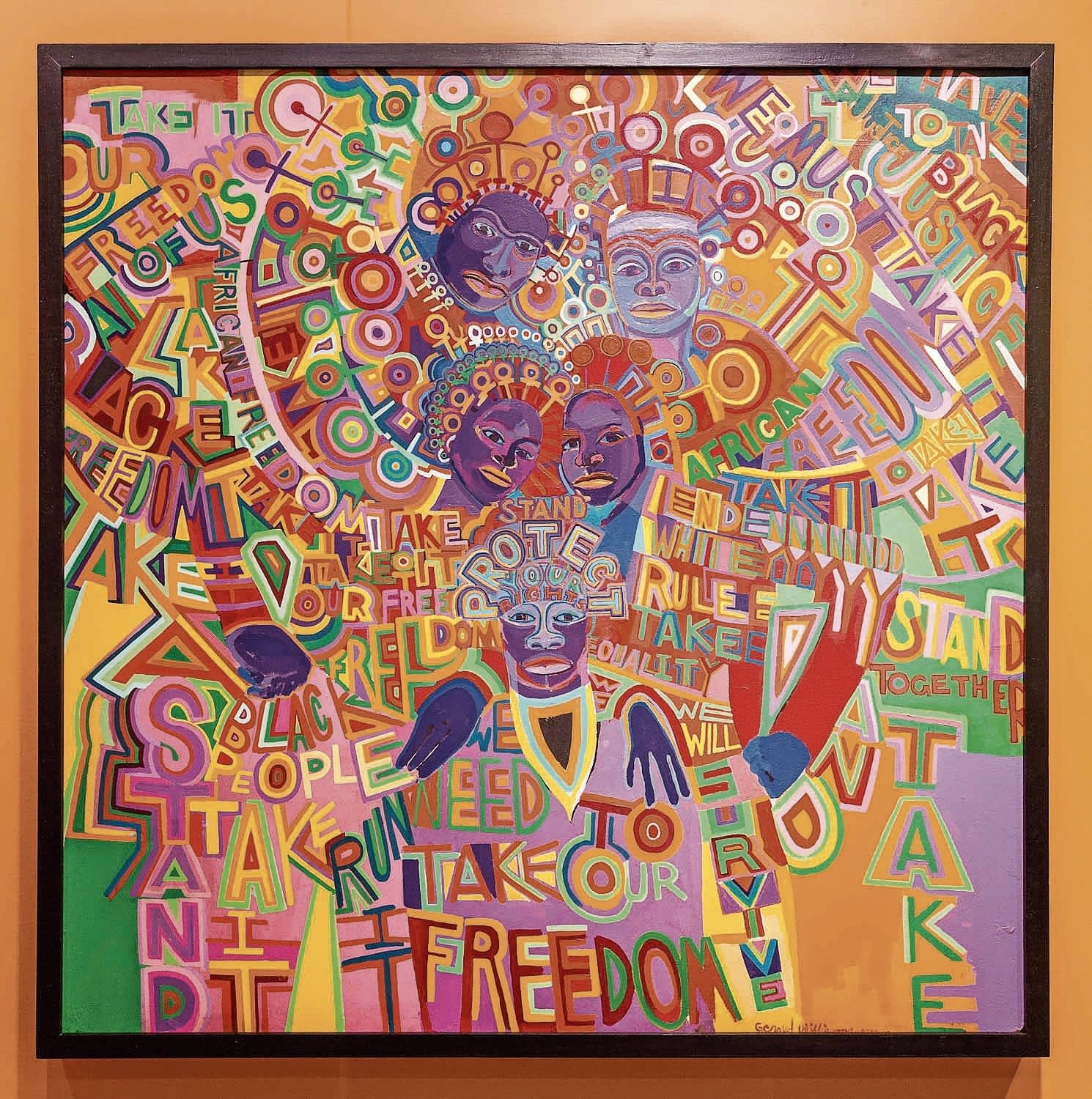

Gerald Williams, Take It, 1971. Acrylic on masonite. Image Courtesy of Sean O'Toole.

The museum’s current focus on new South African art owes a great deal to its current director, James Rondeau, as well as influential collectors such as Chicago-born Pamela J Joyner and Mark McCain, a Canadian living in Cape Town.

In 2019, McCain underwrote the first US exhibition (in Chicago) of the Medu Art Ensemble, an antiapartheid collective of artists, musicians, and writers active in 1970s and 1980s in Botswana.

Joyner and McCain have both contributed to supporting Adams’ exhibition. Occupying two large galleries, Desire Lines is a celebration of Adams’ materialist and collaborative method. Bookended by two atypical figurative wall pieces depicting roses, the exhibition shows the close relationship between the artist’s biography and his work — Adams is a queer Muslim man who worked as a gardener and party decorator before settling into his art career.

The exhibition includes a new large-scale commission titled Epping II. The permeable installation includes both irregular floor pieces and hovering “cloud sculptures” made of wire. The installation enacts Adams’ interest in self-defined walking paths, or desire lines. Principally, though, it is a celebration of growing up on the Cape Flats.

“Bonteheuwel is my home,” writes Adams in one of the autobiographical text panels accompanying his exhibition. “When I was growing up, all I wanted was to get out. It was a depressing place, I felt choked by it. Now I love being there, despite having police vans and convoys constantly driving down the street.”

Much like Chicago’s South Side, a sprawl of majority-black residential neighbourhoods with a violent crime rate 400% higher than the national average, Bonteheuwel for Adams is not reducible to criminal data. It is home, a place where he can be himself.

Connecting the title of his show to his installation Epping II, Adams writes, “For me, a desire line is evidence that people are willing to go against what’s been laid out for them, or what the expectation is for their life. Epping II enacts Bonteheuwel through its landscape, as a fork in the road, created by desire lines, subversive pathways on the ground.”

Igsaan Martin, an art dealer from Cape Town, visited Adams’ exhibition shortly after it opened in April. He was struck by the rich materiality of the works on display.

“My mother and sister are both seamstresses,” explained Martin, who was in Chicago presenting work at Expo Chicago, an annual art fair.

“My mother makes wedding dresses. Everything is hand-beaded. When I see the intricate beading and stitching in Igshaan’s work, it completely takes it back home for me. I don’t only see Cape Town in his work, but my family.”

Raised in Grassy Park, part of a constellation of so-called coloured settlements created by apartheid planners on the Cape Flats, Martin asked organisers at Expo Chicago if he could identify his business, Martin Projects, as hailing from this windswept terrain. Custom, they responded, dictates that galleries are identified by city, not suburb.

An understudy to dealers Monna Mokoena and Elana Brundyn, Martin founded his eponymous project-driven platform in 2020. He risked his own money showing figure paintings by Cairo-based Sudanese painter Salah Elmur in Chicago after attending the fair on four previous occasions as an employee.

Martin met Elmur online in 2019 and in person in Cape Town a year later. He says the fact that they are both observant Muslims had nothing to do with his decision to work with Elmur.

“When I saw his work for the first time I just really loved the faces,” said Martin, whose own collector passions are around vintage comics.

The subjects of Elmur’s full-body and facial portraits draw some inspiration from the poses and styling of prints made in his father’s defunct photo studio in Khartoum. An illustrator too, Elmur renders his figures in reduced, almost cubistic terms. Often they hold leafy props.

The artist’s humanist portrayals of common people share striking affinities with Latin American painters such as Frida Kahlo and Alfredo Ramos Martínez — fertile references in a city (Chicago) with a large Hispanic population. Although a gamble, Martin’s presentation was well received. Many works sold, a fillip to future projects.

Among the 140 or so galleries that participated in Expo Chicago, only a handful represented African artists. Athi-Patra Ruga showed new tapestries and three portrait paintings with Cape Town’s Whatiftheworld Gallery.

Mary Sibande, Right Now!, 2015. Archival digital print, mounted on Dibond, and floated in black frame. Image courtesy of Sean O'Toole.

Mary Sibande had a large colour photograph titled Right Now! (2015) in the booth of Kavi Gupta. This powerhouse Chicago gallery, which has represented Sibande in the US since 2018, also staged a fine survey of works by the black artists’ collective Africobra (aka the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) in collaboration with the Peninsula Hotel.

Founded in 1968 by a group of luminaries from the Black Arts Movement, Africobra participated in Festac ’77, a storied festival of black arts and culture held in Lagos, Nigeria. The American contingent, which included Stevie Wonder and Sun Ra, flew on a charter flight.

“It was a party in the sky,” recalled Jae Jarrell, who with her husband, Wadsworth, cofounded Africobra with three other Chicago artists.

The art market presents an established route to visibility for artists, but it is not the only option. This was the key message delivered by Koyo Kouoh, the executive director and chief curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Mocaa) in Cape Town, in a keynote presentation to industry professionals at Expo Chicago.

Speaking in a conference room filled with mostly North American and European museum curators, Kouoh revisited her curatorial work in Dakar and Cape Town.

In 1995, fed up with her life in Zurich, Kouoh moved to Dakar. She opted for the Senegalese capital over Douala, the Cameroonian coastal city where she was born in 1967, because of its tolerance and care for arts and culture.

In Dakar she met Issa Samb, a founding member of the pioneering arts collective Laboratoire Agit’Art. He exerted a decisive influence on her self-initiated projects. Parlaying local deficiency into opportunity, Kouoh in 2008 founded Raw Material Company, an independent art space in Dakar staffed by women. Today it is a potent symbol of can-do feminist enterprise and bold critical thought in Africa.

“I don’t like the term curator,” Kouoh told her Chicago audience. “I think of myself as a mere exhibition maker and producer, most of the time as a midwife.”

She bemoaned the sprawling meaning of the words “curator” and “to curate” in English, as well as the practice’s associations with gatekeeping in French. “Curatorial practice is a way of caring for society and its citizens, for caring for their vitality.”

This thinking extends to her reinvention of Zeitz Mocaa, which she was chosen to lead in 2018. Early in her regime, Kouoh instituted a programme of solo shows devoted to women.

She refers to the Thomas Heatherwick-designed showpiece in Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront as a container. “A container is only as important as what it contains. No museum has survived purely based on its architecture.”

Kouoh’s bold, provocative and at times unashamedly political keynote emphasised the need for collective action by curators, and the need to formulate projects that are neither beholden to the art market nor mired by strictures of the academy. Chicago’s turbulent South Side is currently host to one such project.

In 2015, local artist Theaster Gates bought the Stony Island Trust and Savings Bank Building from the City of Chicago for $1. Gates, who spent a “formative” year pursuing religious studies and fine art at the University of Cape Town in 1996, has since transformed this neoclassical structure into a hybrid arts centre, gallery and library.

A sign at the entrance to the rechristened Stony Island Arts Bank reads, “Black people matter, Black spaces matter, and Black objects matter.” It is no empty claim. The arts bank is a secure store for the personal vinyl collection of house music legend Frankie Knuckles. Its library is composed of books and magazines donated by the Johnson Publishing Company, producer of Ebony and Jet magazines.

In April 1960, Jet reported that Miriam Makeba “electrified” patrons during her 10-night residency at Chicago’s Blue Note, a reminder of the longer historical relationship connecting Chicago and South Africa. Thirty-four years later, during a performance with Hugh Masekela at Chicago’s New Regal Theatre, a Jet reporter quoted Makeba, “I am so happy now at age 62, I am finally going to vote.”

The consequences and opportunities set in place by that vote are now visible in the vibrant South African art enjoying premier billing in a segregated US city undergoing a renaissance in thinking and doing, not in the canyons of old Chicago, but its urban fringes.