Frieze, the high-ticket international art fair that had its successful Los Angeles debut last year, is having its second outing through Sunday. Seventy-seven contemporary art galleries at or around the blue-chip end of the spectrum, vetted for inclusion by a knowledgeable crew of art-world insiders, are showing their wares in a mega-tent erected for the occasion at Paramount Pictures Studios in Hollywood.

Out on the studio’s backlot, 16 artists were invited to participate in Frieze Projects. Amid the false-fronts of Paramount’s New York street movie-set, they’ve installed works loosely connected to themes of illusionism, myth-making and representation in mass entertainment. Among them are painter and sculptor Sayre Gomez, conceptual artist Tavares Strachan and photographer and video artist Barbara Kasten, selected for the exhibition organized by Rita Gonzalez, curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas, director of the Vincent Price Art Museum.

Gonzalez also has organized “Focus L.A.” inside the tent. That section features several of the city’s galleries.

Once upon a time, it would have been unthinkable for talented curators from the nonprofit art-museum world to participate in a project whose purpose is to supplement and promote a for-profit sales event. Today, almost no one bats an eyelash at the conflict of interest, so common has it become — another indication, as if one were needed, of the degree to which the marketplace now rules our artistic life.

Two decades ago, in an interview with journalist Barbara Isenberg, the late, great artist John Baldessari succinctly observed: “A shark is the last one to criticize saltwater. If you’re immersed in something, you can’t see it.”

As I write, tickets for the Frieze gallery tent and Frieze Projects back-lot installations teeter on the brink of being sold out. (You can check their status at frieze.com.) I can’t say much more about either one. This year, I opted instead to spend the preview day at Felix, a simultaneous upstart fair being held for the second time at the Hollywood Roosevelt hotel.

One of the most productive features of the big fair at Paramount is the extent of the independent programming that immediately grew up around it. If Frieze is the shark, they’re the pilot fish.

On streets surrounding the fair, Santa Ana’s Grand Central Art Center is hosting Yumi Janairo Roth’s performance “Spin (after Sol Lewitt),” in which energetic commercial sign spinners do their whirling thing. (“The artist may not necessarily understand his own art” says one advertised sign.) At the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Little Tokyo outpost, artists and choreographers Gerard & Kelly present performances of “State of,” an athletic pole-dancing display whose strip-tease associations mean to bare charged political points.

Alternate art fairs are numerous.

At the Kinney Venice Beach Hotel is Startup L.A., billed as an “immersive” gathering of work by 60 area artists. The peripatetic Art Los Angeles Contemporary — ALAC by acronym — has relocated from previous outings in Santa Monica and West Hollywood to now occupy the Hollywood Athletic Club, a beautiful 1924 landmark that’s a quick eight-minute drive from Frieze. (Thirty-eight international exhibitors are on view for ALAC’s 11th annual fair.) Downtown, repurposed warehouse space at Row DTLA hosts the second outing of “Spring/Break,” a free-form array presenting individual artists and small galleries.

Felix is perhaps the most ambitious of the alternatives. The somewhat tatty glamour of the Hollywood Roosevelt, across the street from the TCL Chinese Theatre, is the setting where 63 galleries (up from 41 last year) have turned hotel rooms on the 11th and 12th floors, plus poolside cabanas downstairs, into a motley mix of showplaces.

The lighting is bad, many rooms are cramped, elevators are slow (advice: go to the top floor immediately upon arrival, then work your way down), the hallways get crowded, an imperious woman with a small dog in a baby-carriage kept blocking entry through doorways — but none of that really matters. Felix is sociable fun.

There is something about meeting strangers in anonymous hotel rooms.

Familiar midlevel galleries are here, including L.A.’s Praz-Delavallade and Parrasch Heijnen, New York’s PPOW and Anton Kern, and Barbara Weiss from Berlin and Alison Jacques from London. Independent and artist-run spaces such as Mexico City’s cheeky Lulu, New York’s venerable White Columns and Inglewood’s community-minded Residency are also present.

Fine examples by equally familiar artists turn up. Cheerful screenprints by Sister Mary Corita, the 1960s Pop art nun, plus a refined union picket-protest drawing by Andrea Bowers span a range of women’s political art at Andrew Kreps (New York). Groundbreaking Verifax collages from the ‘60s by Wallace Berman — maybe the only artist to have made truly genius work using a photocopier — are at Galerie Frank Elbaz (Dallas and Paris).

You can find surprises too.

James T. Hong, an Asian American documentary filmmaker based in Taiwan, also makes sculpture and video projections. At Hong Kong’s Empty Gallery, Hong shows boxes made from frosted glass, illuminated from within and ostentatiously padlocked.

Shifting shadow-play hints at creepy, undiscernible contents of a vaguely taxidermal sort secreted inside the boxes. A luminous video projection on a side wall is little more than a glowing blur.

Hong cleverly upends the phantoms of Plato’s cave: Break the glass and you’re sure to be disappointed by the obscured, surely conventional source of the captivating apparition, the ghost in art’s machine. Art’s mysterious inner resources might be inaccessible, but they remain magnetic.

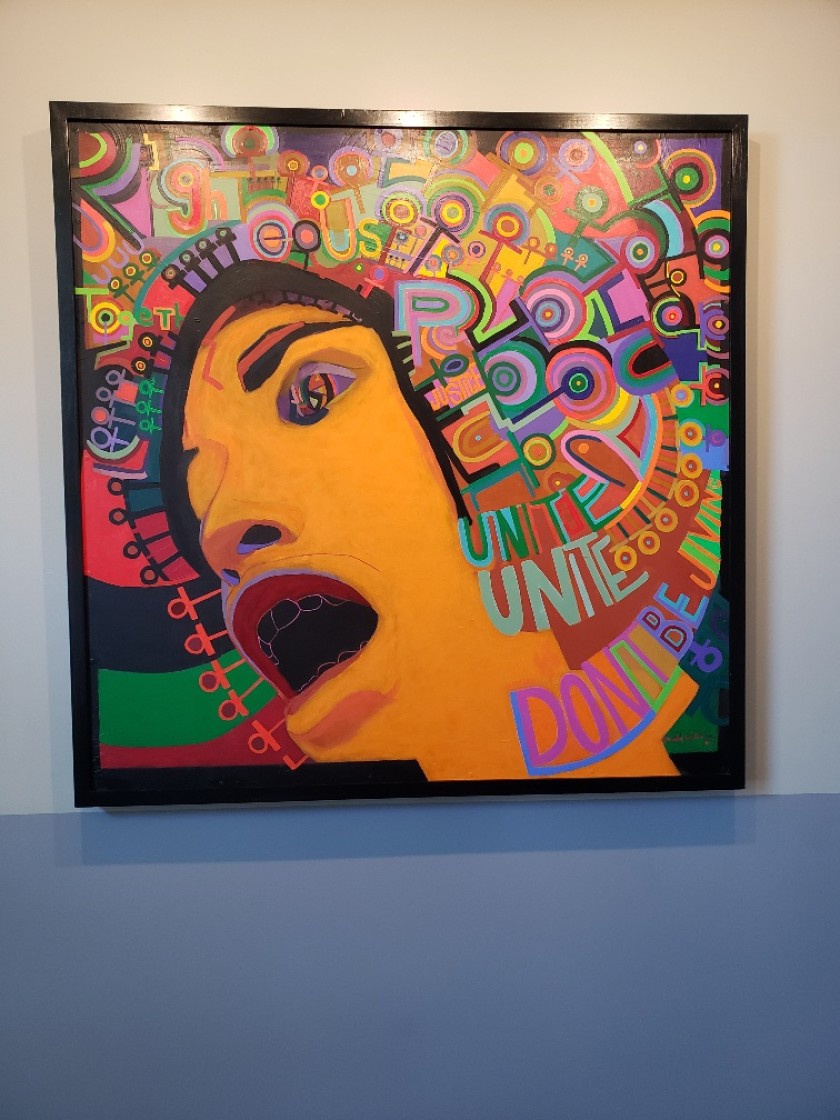

Kavi Gupta (Chicago) has a marvelously loud 1971 portrait of political activist Angela Davis by Gerald Williams, a co-founder of AfriCOBRA, the influential black artist collective. Davis famously refused to be silent in the face of intense FBI harassment, which Williams deftly represents as an open black mouth framed by a fantastic multi-colored Afro on a looming head.

Nearby, “57th St. (after Sunset Blvd.),” a witty 1988 painting by Roger Brown, recasts the classic Billy Wilder movie in the format of a tawdry comic strip. Panels feature thinly veiled pastiches of rising young artist Jeff Koons seducing and abandoning fading sculptor Louise Nevelson. (She died that year.) It doesn’t end well: A limp basketball lies at the bottom of a fish tank, like William Holden dead in Gloria Swanson’s swimming pool.

A number of galleries have attempted to capitalize on the art fair’s location with their selection of work. (Why would anyone bring goofy paintings of E.T., coals-to-Newcastle style, as one did?) Brown’s is among the few that don’t make a visitor groan.

Nor does Jake Longstreth’s large, flat, suitably unadorned “Ontario International Airport,” a visually vacant landscape painting of a bland Radisson Hotel. If you want meta, stop to view the work from L.A.’s Nino Mier Gallery: Longstreth’s picture — reminiscent of Ed Ruscha, although suitably further afield in exurbia — seems especially forlorn within the historic labyrinth of the Hollywood Roosevelt.

If there’s a prize for Best Gallery Name, it goes to Mother’s Tankstation (Dublin and London). A remarkably poignant quilt by Tokyo-born artist Atsushi Kaga is laid out in the sunshine on a patio daybed, its pieced imagery pulling the Japanese comic-book culture of manga and anime into homey British handicraft traditions.

A ghostly spirit-form rises up from a disabled teddy bear resting beneath a tree. An old-fashioned Japanese kaidan — a ghost-story folktale — has been reconsidered for a new Beatrix Potter context. Below the smart, cross-cultural mashup is some stitched text: “Leave me alone ‘cos I’m a nerd.”

Felix isn’t the first boutique art fair in an L.A. hotel. In 1994, an excellent one launched at the Chateau Marmont on the Sunset Strip. The art market had collapsed a few years earlier and was just struggling back to life. Setting up temporary shop in hotel rooms rather than a convention hall was a budget fix, especially as a dealer could also spend the night.

Showing mostly art that could fit in a suitcase, the aura of traveling salesmen lent added charm. That still holds now, even though today’s market context couldn’t be more different.

How different? Last year admission to Felix was free. This year, the four-day ticket is 25 bucks.