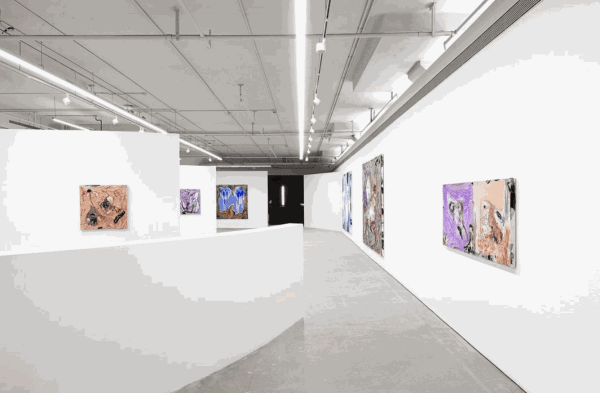

Manuel Mathieu, Silk Road Traveler, Lethe's Wanderer: Longlati Foundation, Shanghai, China

Longlati Foundation is honored to present “Silk Road Traveler, Lethe’s Wanderer”, the solo exhibition of Manuel Mathieu (b.1986, Port-Au-Prince, Haiti) curated by Chinese artist Pu Yingwei, which marks the launch of Longlati Curatorial Exchange Program, a pioneering gesture of the foundation to demonstrate “exhibition as form” when artists are playing the role of curator. The body of work on show this time includes Mathieu’s earlier paintings acquired by Longlati Foundation and new pieces devised around the concepts of traveling, of sea and sky, of navigating on a boat, which are influenced by his discussions with Pu Yingwei. In return, Mathieu will also curate Pu Yingwei’s solo exhibition next year at Longlati Foundation.

The following is the exhibition text written by Pu Yingwei:

Silk Road Traveler, Lethe’s Wanderer

—Manuel Mathieu’s World-Building Painting Comes to China

The greatest power and wealth in the world are nothing but passing clouds.

There is truth to the notion that everything arises from nothing, and to nothing it must return.

Life itself is a great joy. Why remain tied to mortal thoughts and bound by the ages?

Why consume oneself with concern when you can realize dreams and roam free against all convention?

—Journey to the East, Wu Yuantai (Ming dynasty)

The roots of Manuel Mathieu’s current journey to the East can be traced back far into the past, and their echoes remain clearly visible today. Much like now, the world then was mired in a dark night, blindly persisting in all manner of treachery. The streets and alleys were filled with fools, fanning wave upon wave of idiocy, its counterpart a feast of extremes and the expansion of empire. In the chaotic hundred years between the 15th and 16th centuries, the century of maritime navigation, three fleets began their journeys in the real world. The first was that of Chinese navigator Zheng He. On July 11, 1405, he led a massive flotilla of 317 ships, each nearly a hundred meters long, and together carrying nearly seven thousand people, to sail south from the mouth of the Yangtze River. In a total of seven maritime journeys, the fleet made it as far as the entrance to the Red Sea and the East Coast of Africa. Then it was a Spanish fleet led by Columbus, which reached land in the Caribbean Sea on December 6, 1492. He named the land under his feet “Hispaniola.” The Europeans brought smallpox and slaughter to the island, with the local inhabitants, the Arawak, wiped out in the destruction. The third, most notorious fleet set off later to ship Black people to the island from Africa. A century later, this place gained a name of its own: Haiti. One could say that today’s concept of “the world” began with these two maritime expeditions led by Zheng He and Columbus from the Eurasian continent, which also laid the anchor for the diversity framework of identity fluidity for the whole future world. Today, Manuel Mathieu, who was born in Port-au-Prince, raised in Montreal, studied in London, and now comes to Shanghai, joyfully accepts his inherent “worldliness.” The global pandemic has not stopped him from journeying across multiple continents. To the contrary, Mathieu’s creations have rapidly grown in this period, and have enjoyed unprecedented cultural fluidity and fusion.

Manuel Mathieu, Apparition 4, 2022, mixed media on canvas, 227 x 278cm. Collection of Longlati Foundation. Image courtesy of the artist and HdM Gallery.

Echoing these three maritime voyages that took place in the real world in the 15th century are two expeditions that took place in the literary world. In 1494, German poet Sebastian Brant completed his literary masterwork Das Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) along the banks of the Rhine. In this sweeping poem, Brant imagined all of society as a roiling sea, for which he would build a giant ship to conquer the waves. The ship was populated with all kinds of “fools.” They come one after another, each outstanding in their own way, cutting a vivid image through their entanglements of sensitivity and kindness, and various personality quirks. In Manuel Mathieu’s new “Portrait on the Surface” series, the artist has also brought together a band of world-weary travelers to gather on a “ship of fools”: each conceals their own past as they cross the ocean together, but they do nothing to hide their inner turmoil (see The Swells Within). Another literary expedition was launched by a contemporary of Sebastian Brant’s, the Ming dynasty writer Wu Yuantai. His Journey to the East cuts a penetrating portrait of the “Eight Immortals.” The Eight Immortals are not like the multitudes of other immortals in Chinese mythology. All of them come from the world of mortal man, and so all of them have colorful stories from their lives as people. They include a relative of an emperor, a beggar, and a Daoist priest. They were not born immortals, and so they are often a bit “rough around the edges.” For instance, Han Zhongli walks around with his chest constantly exposed, Lü Dongbin has a capricious personality, and Iron Crutch Li is given to bouts of drunken lust… echoing the “fools” of Brant’s ship. In these two literary masterpieces, “passage” clearly has strong symbolic import, but the sages and saints are not the primary concern for either author. Both extradite the divine to the human. Their chants and verses are full of yearning for the crude and bustling mortal world.

Manuel Mathieu’s journey also brings together extraordinary symbolic leanings. In works such as Multiple Sight and Speaking in Tongues, we can almost see people from different regions pressing together, their eyes locking for the first time, yet full of enthusiasm. This joyful reception of “others” likewise represents the multiculturalism that flows in Manuel Mathieu’s blood. In a time rife with identity politics and isolationism, the artist still strives to resist within the framework of reality, and to find reconciliation within himself. In Purple Gaze, Milles Horizon, La Source, The Clouds in the Mountain, and The Witness, we seem to see a journal of a maritime journey unfold, the crossing of majestic mountains and rivers, encounters with wondrous sights, all of it carefully recorded, each ray of sunlight cherished. The final, sublime scene is depicted in the palm-sized sketch Ekur. “Ekur” is a sacred mountain in Sumerian mythology, and also denotes a “foreign land.” Once again, Manuel Mathieu has humbly revealed his reverence for the “other.” To be alone in a foreign land is his lot in life, but just like Ekur, it is also his talisman, a monument standing in his heart.

Manuel Mathieu, The Portrait on the Surface 3, 2022, mixed media on canvas,

227 x 278 cm. Collection of Longlati Foundation. Image courtesy of the artist and HdM Gallery.

The journey, however, was inevitably not a smooth one. In the “Apparition” painting series, the expedition is trapped in an enchanted whirlpool, like the chaotic scene in Rimbaud’s Drunken Boat: “Glaciers, suns of silver, waves of pearl, skies of red-hot coals! Hideous wrecks at the bottom of brown gulfs / Where the giant snakes devoured by vermin / Fall from the twisted trees with black odors!” As the expedition moves deeper, this ferocious sea battle breaks out in a single moment. This sonata of life or death reaches its climax in Les Immortels. These sweeping dimensions, this scale beyond the body, are they not an arduous battle for the painter? In this battle, Manuel Mathieu draws on the story of the “Eight Immortals”: “The Eight Immortals with their magic powers, the poem chanter Lü Dongbin, Zhang Guolao the backwards rider of donkeys, the reclusive practitioner Cao Guojiu, the wandering busker Lan Caihe, the nature-rivaling craftsman Han Xiangzi, and the body-snatching Iron Crutch Li, began throwing their treasures into the sea. Suddenly, they all began to move with great speed, revealing their magical powers, and subduing the ocean.” Sobs, murmurs, howls, and laughter… A collective portrait of life bursts forth from the imagery of Les Immortels, a final settling of accounts for weary, besieged travelers adrift at sea. Should we imagine Manuel Mathieu’s life journey of wandering the globe as an exile with no return? Or is it a journey roaming free against all convention? Wandering constantly, the open road his home, catching glimpses of life’s infinite tension through the cracks in civilization. Perhaps “Silk Road Traveler, Lethe’s Wanderer” is the artist’s vicarious journey toward us.

All of the turmoil temporarily fades from the scene at the end of the journey in A Dance in the Clouds. “Like a dog’s bark at the heavens, or the calls of cranes carried off in the wind, the Eight Immortals left no trace.” The giant vessel on the water suddenly turns into a small canoe, free to wander the azure waters. Adrift with no anchor, carried off by the breeze, it departs from the concerns of the mortal world, to drift like a recluse.

Text courtesy of Pu Yingwei.