-

-

-

“I think a lot of these paintings reflect how I see myself as a female artist. There is a feminist voice behind all of these works. I want to highlight female power, and female power in art and culture."

–Su Su

-

Kavi Gupta presents From Your Special Friend, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Beijing-born, Pittsburgh-based artist Su Su. This exhibition coincides with the inclusion of Su Su’s work in the groundbreaking exhibition Wonder Women, inspired by Genny Lim’s eponymous poem and featuring thirty Asian American and diasporic women and non-binary artists responding to themes of wonder, self, and identity through figuration, curated by Kathy Huang for Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles, CA; and State of the Art 2020 at the Sarasota Art Museum, Sarasota, FL; and follows her recent participation in There Is Always One Direction, the widely applauded exhibition during Art Basel Miami Beach 2021 at the Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz Private Museum, Miami, FL; and acclaimed group exhibitions at The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA; The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; and The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA.

Su Su’s paintings express the complicated interplay of aesthetic and societal influences that inform her daily experiences as a Chinese-born, female artist living and working in the United States. Her early painting education in China was, ironically, rooted in the history and techniques of classical Western figurative painting. Similarly, her most influential childhood cultural interactions were dominated by imported American entertainment products, like Walt Disney movies.

-

-

Su Su considers the work in From Your Special Friend an empathy offering—a gift to replace a lie of diminishment with a multitudinous truth.

The exhibition brings together works from two distinct bodies of work: Su Su’s masterful, traditional oil paintings on canvas; and her more experimental Bombyx paintings, made by injecting streams of oil paint through silk, using a sui generis technique of Susu’s invention.

The Bombyx paintings are so-called for their relationship to the silk moth. The name refers simultaneously to the silk substrate Su Su utilizes for the paintings, and to the enchanting, cilia-like appearance of the paint strands Su Su injects through the silk, which recall the hirsute mane of the Bombyx moth.

-

-

Su Su’s more traditional oil paintings convey the weight and seriousness with which she approaches her craft, while also embodying the lightness and humor with which she confronts the big questions she faces as a bi-cultural female artist. The delicate and intricately composed compositions demand the attention of the viewer, while the glint in Su Su’s eye, the informality of her pose, and the whimsy of the melting Bambis, impish dragons, and voluptuous peaches belie a childlike sense of wonder at a world still full of odd mystery.

In most of the works in the exhibition, Su Su utilizes her own body and face as a narrative point of contact between artist and viewer.

“I think a lot of these paintings reflect how I see myself as a female artist,” she says. “There is a feminist voice behind all of these works. I want to highlight female power, and female power in art and culture. There is also something about me sexualizing myself as an Asian woman, in my way, rather than letting others sexualize me as an Asian woman. I think all of the paintings in this show tell some story of that.”

-

-

It wasn’t until Su Su came to America on a Masters scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University in 2010, and began visiting museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that she gained an appreciation for how Westerners perceive Chinese art history—mostly through the lens of ancient ceramics bearing painted scenes of peach trees, deer hunts, and verdant gardens. Su Su recalls her family deriving utilitarian pleasures from ceramic plates and cups decorated with the same iconography, which she was taught reference the realm of the female goddess Xi Wangmu, or Queen Mother of the West. Prized by Western institutions as idealized emblems of Chinese culture, these objects and images are routinely misrepresented and misconstrued, attributing the iconography and its surrounding narratives not to the proper source of a female deity, but instead to the foibles and desires of male emperors.

Inherent in the work is Su Su’s sense of being caught between two sets of cultural assumptions.

-

-

Su Su’s paintings visually embody the internal and external strangeness of negotiating this type of intercultural confusion, both as a woman and an artist. Her multi-layered compositions depict a hyper-chromatic universe in which one woman’s body and soul are in a constant state of metamorphosis amidst a swirling pantheon of Chinese myths and Western pop culture icons.

“I’ve had plenty of bad experiences. I get checked for stereotypes, as a female, or as an Asian female,” she says. “Once you don’t see me as an individual, that creates distance and barriers. I’m fighting that all the time.”

-

-

“Instead of being angry and frustrated, I would rather provide more, and be more open,” Su Su says. “The best I can do is make myself available—let people have access to me, talk to me, get to know me. That’s the attitude. When you’re open and not afraid and ready to share yourself, you’re more empowered.”

As for the identity of the special friend referenced in the title, it might be the artist; or perhaps the art is a special friend to both artist and viewer.

-

-

“I want to make the work and also myself, as the creator, available to everybody. I made these works and I’m here, and I wish you could join me and look at the work and be involved together. I don’t want to just tell you what the paintings are about, but I would love to be there for the conversation. So it’s all like a gift from a friend, given to friends.”

-

INDIVIDUAL WORKS

-

Moon Face belongs to Su Su’s series of Bombyx paintings, socalled for their relationship to the Bombyx moth, which makes silk. The paintings in this series are made by injecting streams of oil paint through the back of a silk substrate and allowing gravity to pull the streams of paint downward. The image is painted upside down and in reverse with the aid of a mirror. The cilia-like streams of hardened oil paint resemble the fine hairs on a Bombyx moth. The face in this painting is that of the artist. Su Su paints her own image into her paintings as a gesture of feminine power and generosity to the viewer, expressing how much more an artist has to give than just technique, materials, and subject matter. The title contains multiple layers of meaning. The three faces are shown in full, in half, and in quarter profile, illustrating the different phases of the moon. Moon face is also a common slur used to describe people with a rounded face. There is also a Moon Face emoji, which, when the eyes are directed to one side as in this painting can be used to signify secrecy, something shadowy, or even to communicate derision. The moon, of course, is not a source of illumination but is a reflector, something that is like a mirror giving back whatever light or shade is thrown at it. The deep texture of the oil paint on this Bombyx painting reacts the same way, absorbing and reflecting light to various degrees depending on the depth of the paint follicles. Su Su’s practice is guided by the complicated and confusing experiences she has had as an immigrant to the United States. The multilayered subtext of her paintings suggests that nothing about her experience is what it appears to be on the surface.

-

-

-

Titled and composed in the fashion of a traditional still-life, Pears, Moth, and Brushes includes one element not mentioned in the name: a self-portrait of the artist. Su Su includes herself in the painting as a gesture of empowerment, feminine power, and as a gift of generosity to the viewer that states how much more an artist has to offer than simple subject matter. In this painting, Su Su includes pears as a reference to a common element in classical Western still life paintings, and because the pears echo feminine bodily forms. Su Su’s practice is guided by the complicated and confusing experiences she has had as an immigrant to the United States. Her paintings bring together symbolic references, historical cues, and tidbits borrowed from mass media and pop culture to create a jittery, beautiful hybrid image with the capacity to re-shape our understanding of our interconnected world.

-

-

-

This masterful oil painting by Chinese-born, Pittsburgh based artist Su Su portrays the naked figure of the artist surrounded by a swirling, melting universe of Eastern and Western iconographies. References to the Walt Disney film Bambi are intermingling with imagery from the traditional 100 Deer motif found on Chinese flower vases. Su Su’s right hand in the painting is holding a brush; her left hand is mimicking the shape of a deer. Su Su assembles her paintings from an array of iconographies as an expression of her own intercultural experience immigrating to the United States from China. This painting demonstrates how Eastern and Western cultures misunderstand and misrepresent each other’s references. Western readings of the Bambi story focus on the tragic loss of Bambi’s mother, while Su Su sees something different in the story: a narrative of a young deer trying to find its way through life through other animals who are its teachers and mentors. Meanwhile, the 100 Deer vases, such as those found in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are typically described by Western curators as referencing the political desires of male emperors to attain power and long life. The story is one of men overcoming and dominating the natural world. This is, however, a misreading of the iconography, which in reality references the deer who live in the garden of a female deity, the goddess Xi Wangmu, or Queen Mother of the West. Su Su’s presentation of this amalgam of iconographies offers a new and unique understanding of intercultural exchange—a jittery, beautiful hybrid of mass media, pop culture, history, and memory with the capacity to shape our understanding of our interconnected world.

-

-

-

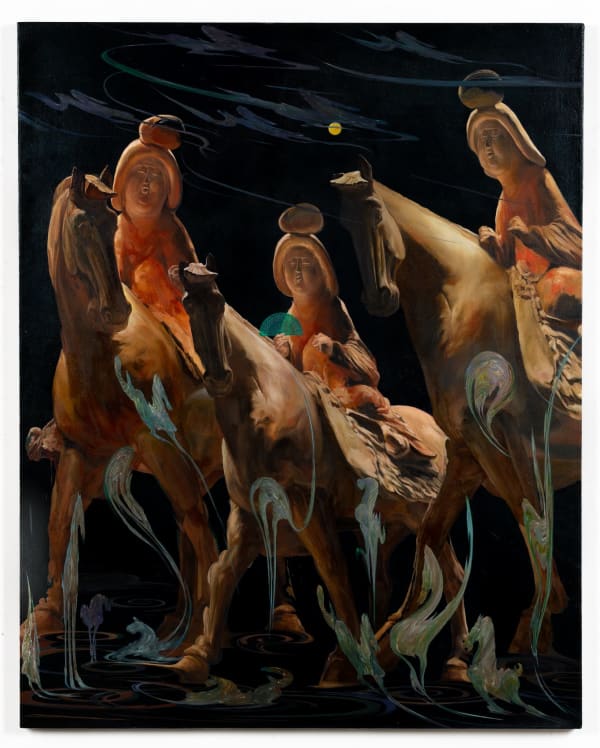

The Anxious Journey and Voyager are part of a series of oil paintings depicting women on horseback. These paintings reference Equestrienne, a sculpture in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, which dates to the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907). The sculpture shows a female horse rider with a relaxed posture, her hands in front of her as if holding the reins. Su Su perceives this woman as calm, confident, and unpolished in her appearance, a starkly different iconography from many contemporary portrayals of femininity.rance, a starkly different iconography from many contemporary portrayals of femininity. “There is nothing saying this is an Instagram-ready picture,” Su Su says. “She’s in a dream life by herself. It touches me a lot when I look at it. There was a time period in history when women lived a life holding their own space, and artists admired that. Instead of making sculptures with fit, perfect ladies holding yoga mats, they made sculptures of ladies on horseback having their moments.” Su Su painted these three women looking down from the viewpoint of someone small looking up. “The sculptures are small,” Su Su says, "but the idea is big, so I made the women big in the paintings.” As a female artist raised in one country and relocated to another, Su Su makes paintings that reflect how she sees herself. “There is a feminist voice behind all of these works,” she says. “I want to highlight female power, and female power in art and culture. I think all of the paintings tell some story of that.”

-