-

Kavi Gupta presents Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground, a solo exhibition of new work by Michi Meko, Joan Mitchell Foundation Grantee and Artadia Award winner. Featuring works created entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic, the exhibition reflects on Meko’s ideas and experiences during isolation. A forthcoming monograph published by Kavi Gupta Editions will examine all levels of Meko's work, studio methods, and conceptual processes.

Solitude is a strange currency—enriching to those who can mobilize its potential; a liability to those who cannot. For many of us, the forced isolation imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing feelings of loneliness. When Meko saw the world going into quarantine back in 2020, he decided to embrace the inevitable. Packing a go bag and heading by himself deep into the north Georgia woods, he instigated an isolation within an isolation, and found visibility within invisibility.

-

-

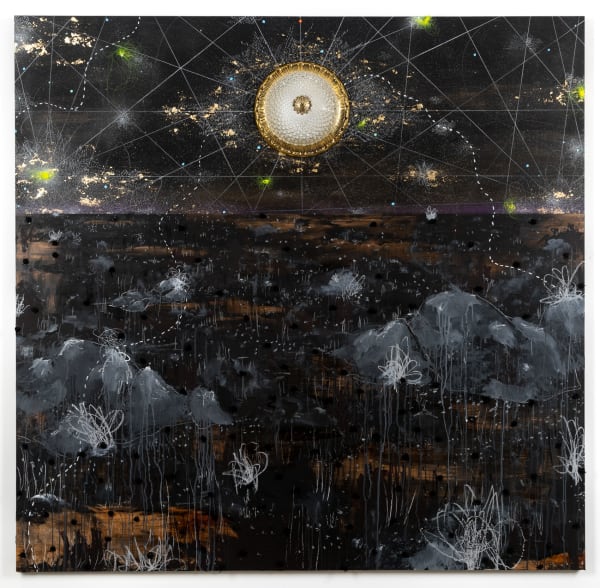

Exhibited within a sound and lighting world evocative of a lonesome campfire in the mountains, Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground symbolically and abstractly depicts both the geographical and psychological wildernesses through which Meko has traveled. Some works are painted from the perspective of being inside the thicket. Some are exhibited high up, so the viewer must crane their head. Several are painted from an elevated, expansive vantage point, what Meko describes as a fugitive view, echoing poet Fred Moten’s description of fugitivity as an aspirational striving for a transformative escape from the bondage of the commonplace.

Some of Meko’s works are pure abstractions. Others resemble childlike hump hills, obliterated by mark making. Where the work is less concerned with representation, it engages more with the inward landscape. “That’s what this work is about,” Meko says.

-

-

Meko’s rigorous studio practice has always been grounded in a material, metaphorical, and philosophical examination of what he calls “the African American experience of navigating public spaces, particularly in the American South, while remaining buoyant within them.” Incorporating romanticized found objects as well as the visual language of mapping, flags, and wayfinding into his work, he constructs transcendent aesthetic spaces into which the viewer’s psyche is free to wander.

Continuing his longstanding practice of activating the allegorical content of his materials, Meko introduces two new mediums in Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground: fish scales and yellow corn grits. An avid fisherman who makes his own lures, Meko blended the fish scales into his paints, endowing the surfaces of his abstracted landscapes with an otherworldly glint and glitter, like silver moonlight reflecting on an effervescent pond. The yellow corn grits, sourced from a local miller near Rabun Gap, an area where Meko likes to camp, add a coarse and weighty earthiness to the work.

“These gestures are Southern gestures,” Meko says. “What we see now in the art market, where there’s portrait painters, I decided to make my portraits of what Black life looks like and take that into the abstract, and paint what that energy of a Black soul looks like. This is a way to get me where a lot of artists aren’t thinking, and to further isolate myself, to push my aesthetics, my philosophy, or pedagogy further beyond the norm.”

Recent exhibitions of Meko's work include Realms of Refuge, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL; Michi Meko: Black and Blur, Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, Atlanta GA; Michi Meko: It Doesn’t Prepare You for Arrival, Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA GA), Atlanta, GA; Michi Meko: Before We Blast off: The Journey of Divine Forces, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA; and Abstraction Today, MOCA GA, Atlanta, GA. His work is held in the collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; King & Spalding, Atlanta, GA; Scion (Toyota Motor Corporation), Los Angeles, CA; MetroPark USA Inc., Atlanta, GA; and CW Network, Atlanta, GA, among others. Meko is the recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant and the Atlanta Artadia Award, and was a finalist for the 2019 Hudgens Prize.

-

-

-

This view from up high through rhododendron leaves evokes a beautiful, free, but uneasy feeling. A fire is burning in the distance below. Something is lingering there. As in many of Meko’s paintings, this piece includes fishing line. “Whenever fishing lines are present they represent pressures that pull on us, or some sort of mistake or failure that has to be corrected,” Meko says. “That’s the evidence of someone’s frustration.” Within the picture plane, such feelings have the chance to be perceived also as things of beauty, suggesting that the materials and echoes of frustrations can be transformed.

-

-

-

The title of this painting references a book by James Baldwin, which itself references the Biblical quote, “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time.” The view in the painting is from the midst of charred woods. Everything is vacant; fire has gone through. The image references a moment of epiphany Meko had while camping during the social justice protests in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. “While I was sitting by my own fire, the rest of the world was on fire,” Meko says. “There was a real moment of guilt that I have absolutely checked out or taken some kind of privilege to put myself in this space and enjoy this leisurely moment of what I call caveman HD, which is a campfire. It’s not having a care in the world but then being aware of what’s going on within the distance.”

-

-

Michi Meko, A Beautiful Free Uneasy: The Rhododendron Cave hide out, 2022

Michi Meko, A Beautiful Free Uneasy: The Rhododendron Cave hide out, 2022 -

Michi Meko, A Fugitive GPS, 2022

Michi Meko, A Fugitive GPS, 2022 -

Michi Meko, By the Fire Next Time, 2022

Michi Meko, By the Fire Next Time, 2022 -

Michi MekoCrappie Painting: Render An Apocalypse. A Life for a Life. How To Kill a Fish., 2022Acrylic, Acrylic 60 Gloss, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil. India ink, Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Mono lament, Gouache, Fish Scales, Fish Glyco Protein Yellow GA Corn Grits, Pur Glass

Michi MekoCrappie Painting: Render An Apocalypse. A Life for a Life. How To Kill a Fish., 2022Acrylic, Acrylic 60 Gloss, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil. India ink, Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Mono lament, Gouache, Fish Scales, Fish Glyco Protein Yellow GA Corn Grits, Pur Glass

Preserve Jars, Wooden Crates on Canvas91 x 66 in

231.1 x 167.6 cm -

Michi MekoCucka Bugs: Cold was the Ground. Barren Trails, 2022Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil. India ink Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Mono lament, Gouache, Wood Satin on Panel75 x 73 in

Michi MekoCucka Bugs: Cold was the Ground. Barren Trails, 2022Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil. India ink Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Mono lament, Gouache, Wood Satin on Panel75 x 73 in

190.5 x 185.4 cm -

Michi Meko, Inna Silk Suit Trying Not To Sweat., 2021

Michi Meko, Inna Silk Suit Trying Not To Sweat., 2021 -

Michi Meko, Oak Catskins: Damn Annoying Squigs. Swollen Eyes By Moonlight, An unseen Painting, 2022

Michi Meko, Oak Catskins: Damn Annoying Squigs. Swollen Eyes By Moonlight, An unseen Painting, 2022 -

Michi Meko, Something like Ezekiel: Waiting for the Transformative Moment, 2022

Michi Meko, Something like Ezekiel: Waiting for the Transformative Moment, 2022 -

Michi Meko, The Ants Can Have My Body: Too Far out to turn back, 2022

Michi Meko, The Ants Can Have My Body: Too Far out to turn back, 2022 -

Michi Meko, The Long View, 2021

Michi Meko, The Long View, 2021

-