Born in Alabama, Roger Brown first came to prominence as an artist when his work was included in the 1969 exhibition, “Don Baum Says: Chicago Needs Famous Artists,” at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Subsequently Brown became known as one of the “Chicago Imagists.” Although best known as a painter, Brown’s work includes significant sculpture, as well as stage design and public art. He recently sold his North Halsted studio in Chicago, his last link to the city with which his work has been so identified, and now lives in California.

Mark Price: Roger, your reputation over the last 25 years or so has been primarily that of a painter, and yet you’ve made some very interesting and striking sculptural pieces. I am curious about what motivates you to make three-dimensional forms or objects.

Roger Brown: The first group of sculptures was inspired by the feeling that the paintings themselves had a three-dimensional quality, so they very easily could be taken as models for three-dimensional works. That’s basically what I did with the early pieces. I got more interested later in transforming furniture, with the chairs and stools that were half building and half landscape.

Price: Some of your sculptural work is geometric or boxlike-forms that often take on architectural features, like Twin Towers (1977). Other works are painted, usually with figures. In others, you take recognizable artifacts or objects like irons or waffle irons, and paint images on them. And occasionally, there are tree stumps in front of or projecting out of a painting, as in the Lewis and Clark Trail (1979). Everything seems to be referential-there’s nothing that one would regard as pure form. Twin Towers, for example, is basically two six-foot-tall skyscrapers painted with windows, people, and clouds.

Brown: That was in ’77. The way I treated the top of the buildings was to avoid simple, straightforward modeling and create the illusion of the atmospheric-it gives the feeling of going up into the clouds. For Snake Building (1977) I did the same things with the building that I do with changing perspectives within the landscape paintings.

Price: I know that you’re interested in architecture of many kinds, and that when you travel you pick out places that seem to have interesting architecture. Why is architecture important?

Brown: When I first started painting in Chicago, the neighborhood buildings were always very symmetrical and often had a human quality to them. They almost looked like faces and maybe that’s part of it. Schizophrenics see things in objects, and as an artist you’re always kind of borderline. In Chicago, a very interesting city architecturally, you can hardly escape architecture’s influence. As a young artist, I was also influenced by Robert Venturi, who came and lectured at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I read Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) -Venturi’s first book. It was very difficult reading, but there were things in it that inspired me. It was about ambiguities, and something that fascinated me in painting was the quality of illusion. M.C. Escher made it into a game, and ultimately his works are more of a game than they are works of art.

Josef Albers could make it into a work of art, still using the same illusionary tricks. I got interested in those kinds of spatial illusions in paintings, and I tried to do more complex things like Snake Building, where I work up the building into planes. My buildings also lean, like the tower of Pisa. That was inspired by seeing Mexico City, where a lot of the taller buildings are built on a lake bed and do not have good foundations and are leaning. It was funny to walk around the city and to see buildings tilting in different directions. I did a lot of paintings based on that.

Price: Illusion is easier to manipulate in painting.

Brown: It is. In sculpture the illusionary quality is harder, but in a piece like Twin Towers, the painting adds to the illusion.

Price: Twin Towers is on a human scale. You’ve made the viewer a giant and his head is in the clouds next to the skyscraper. I think Twin Towers probably would not have worked as a painting.

Brown: I did paintings like that too.

Price: But putting the viewer in the same space is different.

Brown: Yeah, it’s a different experience, but I have done that same atmospheric thing within paintings. The experience is different, totally different.

Price: What about the irons?

Brown: The first iron I did was for a combination of a chair with an ironing board called A View From Marblehead(1975). I liked making the iron for that piece, and so I made a whole bunch of irons. I started seeing different irons for sale, buying them up, and painting them with car-body paint.

Price: What provoked you to actually paint on the object itself rather than doing a painting of an iron and then painting windows and people on the painting of the iron?

Brown: I’m not interested in just copying something that exists. It wouldn’t be a challenge to draw something the way it is. To me it would get into a kind of Surrealism within painting that I’m not interested in. When the object is in real life and you do that to it, it’s a different thing. One to me is illustration and the other isn’t.

Price: You bring up Surrealism. Would you agree that it has something to do with not only your sculptural work but also your painted work? That there are certain elements of it that are surreal, or maybe visionary is a better word, and that you create visions, sometimes apocalyptic ones?

Brown: I was inspired by Surrealism. But I never considered what I was doing surrealist. It all, in a sense, could be real; it’s only stylized or transformed by my own way of seeing things. It’s not transformed into the fantastic. There are exceptions, I guess, like some of my “Disaster Series” (1972) paintings, buildings falling apart in ways that wouldn’t happen, but even that isn’t quite surrealistic.

Price: In the sculpture, have you been influenced at all by Dada?

Brown: Oh, yeah, sure. When I saw these irons I got to thinking about the things in the Dada movement that were like that. I’m sure that on a subconscious level, a lot of that knowledge is down there working, whatever you’re doing. It’s not a conscious thing, but it plays on your knowledge and awareness of things. Naturally it’s what goes into your ultimately seeing things differently.

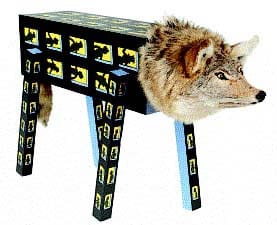

Price: The Wolf Building (1986) could be called a Dada object-a building turned on its side, painted on a small scale, with somewhat comical silhouetted figures in the windows, all of which are held up by legs that are actually like miniature buildings themselves. A real wolf’s head and tail are attached. It’s plausibly an animal, but the elements don’t belong together. The scale is wrong. The wolf’s head is actual size and the building is not actual size.

Brown: That particular piece is more like Dada or Surrealism, and maybe so is the building I did with the lady with a pheasant hat and high-heeled shoes-a little old lady. It’s titled All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go (1990).

Price: Are there any people today whose sculptural work interests you? Are there any sort of impulses out there in sculpture that have some resonance with you?

Brown: Cliff Westermann always did, and so did Luis Barragan, the Mexican architect who died about four years ago. His work was so sculptural. I like Edward Kienholz’s three-dimensional structures a lot. And if you go back, I like Brancusi and, of course, African masks and sculptures. I also like Martin Puryear’s stuff a lot. He used to live in Chicago too, before he moved to New York.

Price: You’ve acknowledged influences like Aldo Piacenza’s cathedral birdhouses. What is it about that sort of thing that appeals to you? Are you willing to call him a folk artist?

Brown: I’ve always sort of chalked that up to being a Southerner, and having grown up partly at my granddad’s cotton farm. People built things for themselves then, and my dad made a lot of furniture for us. So we had a lot of handmade things around the house. That kind of thing inspired me. We had in our family this beautiful, old spinning wheel that was actually made by my fourth great-grandfather for his daughter when she got married. It’s this huge wheel. It’s not manufactured. The handmade qualities are very elegant and simple and, in a way, like Shaker stuff. In school I was also interested in primitive painters. It all kept me stimulated.

Price: William Christenberry is another Alabama native who has moved away from the South. Do you have any feeling or affinity for what he does?

Brown: To some extent. I like his pieces. They’re very model-like in form, and I think they’re beautiful. I guess there’s an affinity. I mean, he has an interest in the same kinds of old nostalgic things. It’s not completely nostalgia, it’s just an interest in really beautiful old things.

Price: The specificity of what he does and what you do-the literal quality-is common to both of you, each in a different form. I wonder if that is something uniquely Southern.

Brown: I think literalness is. Definitely. But I think you can generalize too much. Abstract artists do come out of the South too, like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

Price: But they didn’t come from Alabama.

Brown: No, Rauschenberg came from Louisiana. But he grew up in the Church of Christ, just like I did.

Price: What is the particular appeal of naive or folk or visionary artists for you? Do they hold more appeal for you than the trained artists, the ones in the history books?

Brown: Well, it depends which ones you’re talking about. If you go back to early Renaissance, like Giotto and Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico-those people who are often referred to as the Italian primitives, because the educated way of painting hadn’t come into existence yet-the scientific method of creating real space was not something they were after. And to me the quality of mystery and believability is more beautiful than the illusionary paintings of the late Renaissance. I think, interestingly enough, if you look at modern primitive painters, it’s almost as if they paint and draw the same way as the Italian primitives. Their way of showing perspective-flattened space-is a natural way to draw if you don’t know the Western Renaissance tradition. They continue a tradition that was wiped out by the Italian Renaissance. I try to do what I recognize as what I like in that art. Obviously, I know about things that the primitives didn’t know about. But I choose not to use this knowledge because I don’t like it. It doesn’t inspire me as much as the earlier tradition.

Price: Also I was curious because some of the objects that you work with, the artifacts that already exist, are toys or toylike. Is there some- thing about the scale, or for example, playing with toy trucks as a child, that might have had some influence on how your sense of scale works today as an artist?

Brown: Sure, that goes hand-in-hand with my paintings that grew out of folk styles, and going to the movies. These objects relate to playing with model trains and other toys.

Price: The scale of your figures in your paintings and on some of the painted objects is small. I get a sense that the artist is God, physically-a larger being in a small universe, where the people are minuscule. And because there are so many of those little creatures, there is a sense of community, though maybe the people themselves aren’t aware of it. Scale is a really important part of what you do. It’s almost a part of your signature, I would say, stylistically. That refers to your paintings, sculptures, and painted sculptures. Are any of those interpretations close at all to how you feel about making tiny figures?

Brown: No. The scale is whatever it’s going to be. It’s very similar to what’s printed on a toy streetcar and things like that.

Price: What kind of workshop do you have? How reliant are you on shop tools?

Brown: I had a great saw I bought for myself early on when I first bought my building in Chicago-a Rockwell Unisaw-which is the best carpenter’s woodworking saw you can have. It’s the one Cliff Westermann had. At the Art Institute, the saws were like that too. I learned early on that having the right tools makes all the difference in the world. Otherwise, you’re making a lot of work for yourself. And so I have pretty good woodworking tools. I didn’t take classes in sculpture, but I’ve always been interested in objects. Most of my collections have been objects. It came pretty naturally for me, though my sculptures are no Westermanns in terms of handicraft. Mine depend on building something underneath that generally is painted over. Consequently you don’t become aware of the imperfections as you would with a Westermann where the natural beauty of the wood shows through and craftsmanship is important.

Price: Did you make things when you were little?

Brown: I think I was a little kid like most kids-boys-who get together and build little cardboard things. But, no, I didn’t really. I was too impatient as a kid to do much of anything like that.

Price: Do you have any sense of why you did not take sculpture courses at the Art Institute?

Brown: I was interested in painting. I really didn’t think about one versus the other.

Price: Can you talk about what led to Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama (1974), the back of which is referred to as Mammy’s Door, and what materials are in it?

Brown: That was the first one that I did where the painting has a little stage at the bottom, a little Mobile Bay portion with a boat on it. That was the beginning of my doing three-dimensional things along with painting. In those I would call upon my knowledge of the Cyclorama in Atlanta, which I saw as a kid. To me that was art. I was impressed, and it’s still impressive to me to go there and see it. The illusionary quality is not as effective for an adult as a child, but it’s still pretty effective. That piece started as a painting and grew into an object. I wanted to make it a painting shaped like Alabama and then as I began to finish it, I began adding parts on it, like on the front, filling in this part with the siding of an old Southern house, and then making the back of it like the door that was in my great-grandmother’s house, just an old primitive door with a “Z” frame.

Price: The door has pegs for hanging coats, and it has writing on it, and it projects on a perpendicular from the wall?

Brown: Yeah, it has hinges, so it swings out, back and forth, and has a mirror underneath, so underneath this portion, if you see it, the whole thing in a mirror is shaped like half of a guitar. And I use it to symbolize my great-grandmother having sung the old Appalachian folk song, Barbara Allen, to us as children. I think the back of it-I think I began to think of Westermann, too, as I was working on it-I think it has more of a Westermann-like feeling to it, painting the back, just using the wood, the natural wood. There’s nothing complicated about the way it’s put together. It’s very simple.

Price: Did you do all the construction yourself?

Brown: Yeah.

Price: The Fishing Expedition Chair (1975) is a chair with a landscape on the seat. It’s still a chair and in a way it invites you to sit on it, and it has a very strong identity as a fisherman’s chair. But it’s also a work of art, so it says “just look.” It has a kind of playful quality inviting you to sit on the image. Do you fish?

Brown: I did in high school, quite a bit, but I got away from it. My dad will go with me sometimes when I’m at home. He’s a big fisherman.

Price: What do your parents make of your work?

Brown: I think they understand it because they know me. Obviously, the women that are in my paintings are my mother, and the men are my father. They are all silhouettes of the early memories I have of both of them. My mother just told me today that about a year ago she threw out all of her high-heeled shoes. She must have had 30 pairs. I said “Oh, no! You mean things that went back into the ’50s?” I wish I’d known, they’d probably make a great collection. Her silhouetted figure throughout my paintings shows her with strict, high-heeled shoes from the ’50s.

Price: The piece that you did in ’85, Galvanized Temple, has no figures in it. There doesn’t appear to be any painting on it. It seems to be a construction of galvanized metal roof and garbage cans lined up. It seems to be closer to what I would call mainstream sculpture, particularly with the interest in architecture that you see today in a lot of sculptural work.

Brown: I did that as a part of another group of three-dimensional paintings using neon. I did two paintings. One is a very large one that I own myself. Right after I moved into a house in New Buffalo, Michigan, I had neon tubing put down along the boardwalk from the road up to my house-about 700 feet. The neon was blue changing to dark blue changing to blue-green, all about 10 inches off the ground. It was a lot of fun. It was something my friend, George, wanted to do. He was my partner and he designed the house before he died. So I did it, making it up as I went along, hoping it would be more or less how he would have done it. But I got so fascinated with it, I put it in a couple of paintings later on. In working out the later paintings, I also went back to an old drawing that I had done when I was working on some of those earlier groups of paintings. I thought I would do the front of a bank, using two galvanized garbage cans, turned upside-down because they looked like fluted Greek columns. I thought I would do that with a pediment-I had a drawing for it-and so I started working on that again as a drawing. And then I just extended it and decided to make it into a full “Parthenon.” I used six garbage cans that a sheet metal guy in LaPorte made for me, and a galvanized gutter shaped like a Greek cornice. I wanted to keep it pure, and I wondered whether I should paint it white and then decided to leave it just like it was because it was all this beautiful galvanized metal. You can’t improve on the basic structure.

Price: What about the mosaic project on the building in Chicago? What did that involve?

Brown: That’s at 120 North LaSalle, a building by Ahmanson Company for Home Savings of America. They’ve always done their buildings with art as a part of the architecture. They designed the building with a space for mosaic at the entry to the building. It begins above the door and curves out like a barrel vault, 54 feet long and 26 feet high. I’d always wanted to do something large like that-a public project. I didn’t think a horizontal view of a city or a landscape in an overhead space was the right thing, so I proposed doing Daedalus and Icarus. I realized it needed to be done as if you were walking under the sky, with things floating above you, like a Baroque ceiling painting or a Byzantine mosaic-with Daedalus and Icarus flying overhead. I’ve done another mosaic since then, for the General Services Administration in New York, and it’s 10 by 14 feet. It’s a new courthouse building. It’s inside, but you see it from the outside. I’m doing another one for the Howard Brown Medical Center in Chicago, which serves people who can’t afford medical care.