To ask Jeffrey Gibson about how he came to art-making is to hear a story about connection. Raised abroad, away from his Mississippi Choctaw and Cherokee relatives, Gibson regularly made drawings to send to family members as a child. Upon returning to the States, he found companionship and mentorship among his high school and junior college art teachers. And as he attended the Art Institute of Chicago, the city’s house clubs that drew in other queer people of color allowed him to lose himself to the music on a caring dance floor.

This history cannot be divorced from Gibson’s work. It is perhaps due to these early experiences of the arts as a mode of community building that Gibson’s most recent works stage important conversations about queer and Indigenous collectivity, belonging, and futurity.

Since 2004, Gibson has gained tremendous acclaim for his bold multimedia and multidisciplinary pieces that have found homes in the most prestigious of private and public collections, from the Whitney Museum to the Smithsonian. As I sat with Gibson in the office of his schoolhouse-turned-studio in Hudson, New York, he explained that with “Infinite Indigenous Queer Love,” his fall 2021 solo exhibition at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, he is invested in revisiting, refining, and remixing the signature styles for which he is best known. Moreover, he explains that the fringe installations, paper works, and videos that comprise this recent body of work seek to push against the clean lines of a modernist impulse by forcing his viewer to be fully immersed in the sensorial.

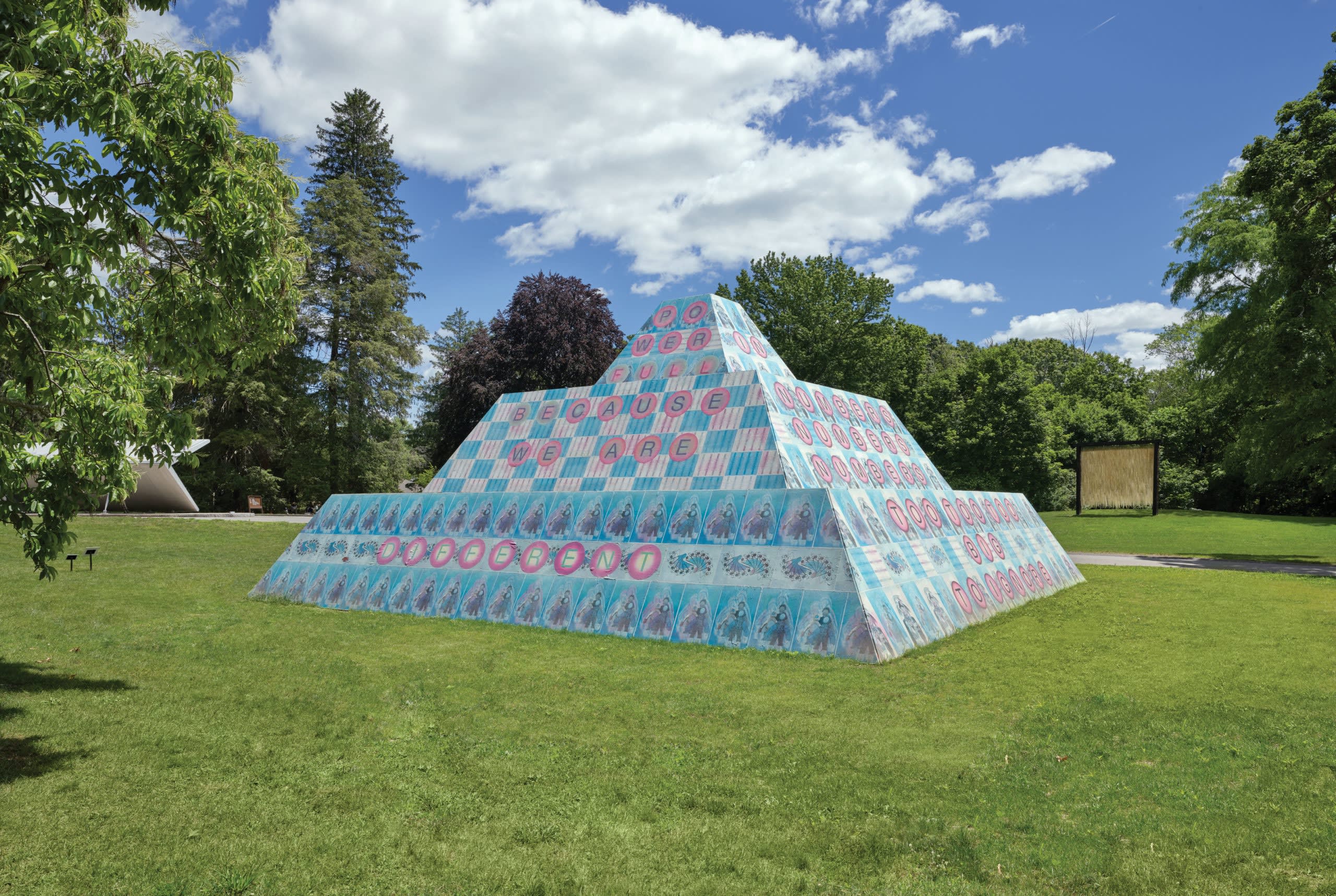

This summer, Gibson’s Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House made its way from Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City to the deCordova’s front lawn. The gargantuan sculpture, whose aesthetics pull from the earthen mounds of the pre-colonial Mississippian city of Cahokia, is presented as a deeply layered site that eschews notions of property. By inviting other artists to activate the sculpture through performance, Gibson also rejects the notion of singular artistic brilliance, foregrounding collaborative processes of creation and meaning-making.

Paper, paint, and beads. Plywood, wheatpaste, and video. There is a lot politically at stake in the amalgamation of these mediums, which I discussed with Gibson two months prior to the opening of his solo exhibition. With this work, he invites viewers to consider better ways of being in relation with our world and one another.

The following is an excerpt from our longer conversation which was held in August of 2021 prior to the installation of Gibson’s installation at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

Mary McNeil: Is your work shaped at all by relationships to particular places of meaning?

Jeffrey Gibson: Like locations?

MM: Yeah. I’m especially thinking of that because Chicago—where you attended art school—is a huge house music city, right? And the title of your sculpture that’s now at the deCordova derives from a house song.

JG: I guess music has always been important to me. I remember my mother listening to Motown and my dad playing Prince. And when I moved back to the United States in the late ’80s, the cliques in high school seemed to be connected by music. And all my friends were definitely sort of like punks and mods, which eventually evolved into the arty kids. We would go into Washington, DC, and we discovered this club called Tracks. Tracks was the way that lots of people describe their destination nightclub: “30,000 square feet of freedom.” And that’s where there was some house music going on. There was industrial music. There was pop music. But I guess just the fact that it was created by queer men in their 50s and 60s—that was sort of their place. I really didn’t realize at the time what they were experiencing in terms of the AIDS crisis. They were always so kind to us. The importance of that community and that music to me at the time was kind of organic.

Then, when I moved to Chicago, there was definitely a racial split between the clubs, especially gay clubs. There was Halsted Street, where everybody was white and muscled and “gym bunny.” And I was like, “This is not my scene.” And then there was a club called the Boom Boom Room and a spot called Red Dog. And it was just purely house music. I’m not someone who was like, “Oh, I’m into Chicago house.” It’s just sort of what I gravitated towards. [With Chicago house legends like] Frankie Knuckles and Derrick Carter, I remember their sets being joyful. I remember them being soulful. And I remember you could just kind of lose yourself. You could just put everything down and just go in and dance. And I always loved the kind of care that you had for strangers on a dance floor. You didn’t have to actually even know each other.

MM: Very ethical.

JG: Yeah. It was very respectful. In this kind of potentially chaotic crowd, everyone’s actually making room for each other and it was great. And that really had the biggest impact.

MM: I would love to talk more about Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House. Why that particular lyric? How does it relate to your vision for the sculpture?

JG: Well, the song that samples this lyric, “Can You Feel It” by Mr. Fingers, has kind of become one of the anthems for house and the kind of inclusivity that I think the origins of house were meant to encompass. It was really for

everyone. It was like, you come in here, you respect yourself, you respect the other people, you are house.

I think “Can You Feel It” is also very much a song about abundance. It’s about collectivity. It’s also about you being an individual, but always being a part of a larger body. And with Indigenous structures…especially the larger structures, they’re built for communities.

With someplace like Cahokia and the Mississippian mounds—first, it is architecture, right? Despite the fact that many never think about these pre-colonial histories as architecture, we do have an architectural style. We do have a use of materials and the design is really there to support function and to support the way that society is structured. [The mounds had] events and ceremonies held within them. There were burials within them, and then the mounds would accumulate as they were built up. To me, it is a form that is somewhat controversial in the sense that if we acknowledge that Mississippian culture was a fully realized civilization, that is completely counter to the way that we think about civilization, that pre-colonization, “there were no fully realized civilizations,” which is simply not true. So, this sculpture is just sort of like, “We don’t have to make it up. Here it is. They exist. Here they are.”

MM: To me, this appears to very much be a sculpture that is contending with questions of land, space, and belonging. What is the relationship between the sculpture and the larger environment it inhabits?

JG: When I was thinking about a structure, and when Socrates Sculpture Park, where it originated, asked me, I knew that the sculpture needed to be big. [Socrates is] a hard space. It’s easy for something to get lost in there. It really started off as an experiment. I think the idea of collaborating with people came about after years of working with a team here [at the studio] where we make things. But also, I really feel that ethically, I don’t need to go and learn somebody else’s knowledge necessarily if I can invite them to come in and contribute it.

MM: Right, it’s not extractive. And with that space, you invited several other Indigenous artists to activate the structure both at Socrates and deCordova. Can you talk a little bit about the importance of collaboration with this piece?

JG: It was really just an invitation. It’s like, “Of course the structure is yours to do whatever you want with—if you want to nail into it, if you want to climb all over it, if you want to paint it.” I remained very open to everything… The first three collaborative artists, Laura Ortman, Raven Chacon, and Emily Johnson, are people who I’ve known for some time and have wanted to collaborate with.

Eric-Paul Riege and Luzene Hill both performed at deCordova. Eric-Paul is this young performance artist who I’ve watched for probably the past five years and is someone who grew up within a weaving family. He has conceptualized weaving. It’s the foundation of his visual language. Luzene Hill is somebody who was always a practicing artist, but in her sixties, decided to really commit and go full-time into art-making. I saw one performance of hers about five years ago, and I was like, “Wow, this is really evocative. And why have I never heard of this person?”

We wanted to present something that is a platform for people to come and do what they already do. And so the title, Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House, becomes somewhat explanatory. It’s just sort of the notion that it’s not really anybody’s house. Anybody can be the “my,” and anybody can be the “you,” and then inevitably there’s an “our.”

MM: Yeah. I love what you’re saying about the piece as eschewing notions of property or ownership and emphasizing collaboration. I’m also interested in hearing about the sculpture’s move to Massachusetts. Did this new location change the way that you think about the sculpture?

JG: I mean, it has definitely been a learning process. When I initially proposed it, I kind of half expected Jess Wilcox at Socrates to say like, “Oh no. We can’t do that.” And when she didn’t, I was like, “Oh cool.” And then she positioned it in the context of monuments, which is something that’s always made me feel uncomfortable—monuments in general. And so I said to her, “Well, I don’t know if I would actually create a monument, but I suppose if I was to think about a monument, I would certainly want to spotlight histories that haven’t been celebrated.” In my dream world and an endless budget world, we would be able to offer that and support anything anyone wanted to do on [the sculpture].

At Socrates, I felt like we were just kind of rolling along. We got a big boost of financial support from VIA Art Fund. And that allowed us to actually go from it being more of a visual structure to giving it the engineering support so that we could put hundreds of pounds on any square inch. So, because that thing was actually built as a structure, there was so much more that we could do with it. Then COVID happened and we couldn’t have audiences, we couldn’t gather, and we couldn’t go inside.

MM: On the inside of the structure?

JG: Yeah. The inside is so cool. We’ve been working on these films to document the performances that couldn’t be experienced in person. For the last video that we shot in Long Island, we shot a lot of it inside because the idea was that with any of these Indigenous structures, there’s always the difference between how we might see these images in books or archeological renderings, but the material culture happens on the inside. The ceremony happens on the inside. The feast happens on the inside. The storytelling happens on the inside. Usually, the fire happens on the inside. So for me, that idea of the interior has always been important and maybe is less about public and more about intimacy and privacy.

Long Island City is a very multi-ethnic area. At Socrates, we were hoping to engage the different communities there. There’s a Middle Eastern community that we didn’t get to engage with. There’s a subsidized housing community. There’s a voguing house close to the park that we didn’t get to engage with. Socrates [basically said], “You can be as loud as you want.” So then when the piece moved to Lincoln, Massachusetts, we were in a predominantly white area… It’s somewhat of a monitored neighborhood community where we have regulations about sound and time. Boston has always been so good to me, like so supportive. I know that there has [historically] been some tension between the city’s museums specifically with Indigenous people. And I’ve come to realize over the past ten years, “Oh, when you’re an artist and you’re traveling, of course you get treated really well. You’re not living there.”

MM: You have me thinking here a lot about the politics of space, particularly for Black and Indigenous communities. In my dissertation, I’m writing a lot about Black and Indigenous relationships to space and place, and particularly how communities push back against settler-colonial and anti-Black ways of trying to evacuate or reject us out of space.

JG: Absolutely. And I think maybe also living up here [in Hudson] and thinking about the history of Indigenous people here and seeing people wanting to do better, there’s so much at stake in actually doing it. And so I guess it’s a combination of the sculpture moving to Massachusetts, but also just me shifting as a person. I’m thinking that there’s more that this project could be, for sure. The collaborative list is kind of endless.

MM: Previously, you mentioned that you weren’t a fan of the idea of a “monument.” Could you talk about that as it relates to this work?

JG: To me, monuments are very outdated, and I don’t know if they need to be reinvented to be honest. They celebrate or comfort or preserve the memory of a small group of people. The problem with that is that it encourages the dismissal of other narratives. When monuments present that singular image of the subject, it disengages with time. It disengages with contemporary history [and] environment. It’s a weird way of choosing to frame things. Even the ones that have been pulled down, I just feel they’re still there… I really believe that any material transfers energy, and I’m like, “That is a material that is still holding this particular power.”

MM: Yeah, they just go into hiding. And like you said, that energy is very much still there. As you’re talking about Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House, I’m hearing that it is a sculpture that suggests we destroy the language of monumentality. Or maybe it’s a monument to what can be: Indigenous futures, queer futures, Black futures, or concepts like abundance, safety, and joy. Are these themes being carried into the forthcoming exhibit at the deCordova?

JG: Yes, but I’ll backtrack a little bit. I created a body of work that was shown in early 2020 at the ADAA fair, and it used a lot of texts from religious references. A lot of people don’t know, but both of my grandfathers were Southern Baptist ministers and founded their churches in Mississippi and Oklahoma. My one grandfather would preach in Cherokee. My other grandfather would preach in Choctaw. The hymns and the Bibles were all printed in these languages. And I remember going to church and always being like, “I know we’re saying this is Christianity, but…”

MM: It’s different.

JG: Right. Something else is going on here. And the church was really taught to me as a structuring element of any community. And I was raised to kind of believe that you should go [to church] and you should learn, but you don’t have to pick this up, you don’t have to become a Bible banger. So that 2019 through 2020 body of work includes religious phrases and lyrics. And then some of the other phrases are like, “BRAND NEW DAY.” They’re very sort of aspirational. One of the phrases is “INFINITE INDIGENOUS QUEER LOVE.” I remember, when I chose those words, thinking about how love is oftentimes a theme in my work. And I wanted to use the word Indigenous, and I decided to throw queer in there

because that brought in a lot of the language that I was using and people were using to talk about my work. The funny thing is that my gallery told me that collectors would come in and they would say, “That’s the best piece, but I’m going to go with this other one.”

MM: Really? Why?

JG: I’m always interested in how indigeneity is something that people feel that they have—I’m sure they would say out of respect—to leave it alone… I think people feel like there’s a specific way they have to approach it… So out of the whole series, that’s the only one that’s left. It’s been shown numerous times and it’s still there. But I know that it is an important painting. And it was only shown at a fair. That painting needs to find its way back into the world at some point. So when Sarah Montross asked if I had a title for the deCordova exhibition, I said, “Yeah, I want to actually pull out this one piece and use it as the core…” So we’ll be showing Infinite Indigenous Queer Love.

MM: It’s so interesting to hear how your past work and its reception is influencing this new show at the deCordova. Were there other sites of inspiration for you?

JG: Actually, the sculptures that are going to be inside the gallery also came kind of intuitively. I’m going to jump all over the place here, but I had never watched 2001: A Space Odyssey until this past summer. But it’s not that complicated. So basically, the monolith—

MM: The thing that emerges.

JG: Yeah. The thing that emerges, it’s representative of what at that time was seen as a future. It was also a representation of modernism. And the problem with modernism is that—much like the monument—it puts forward a kind of vision that disregards all of the messiness of life. They were like, “We’re going to be all angles and clean and surfaces and reflective and white. Pattern has gone. Color is gone.” And somehow this is what evolution looked like? And so I was thinking, “How could I indigenize and queer a monolithic, huge sculpture?” And then I was like, “Fringe.”

MM: I love that!

JG: So the sculptures, as we know them now, are going to be nearly twelve-foot-tall blocks of fringe that hang from the ceiling and you can walk around them. When it’s that much fringe, all you want to do is touch it. All you want to do is walk through it. And it’s amazing. Sarah Montross and I have been discussing how to talk about these sculptures. [We’re asking] “How does this reflect queerness? How does it reflect indigeneity?” I was thinking, when I say “infinite Indigenous queer love,” am I speaking about something that I’m looking at and describing? And I’ve realized, “No, not at all. It’s my love.” I am queer and I am Indigenous, so it’s my infinite Indigenous queer love. That opens up [the exhibit] to really anything. As a visitor, you don’t have to be queer. You don’t have to be Indigenous. I am bringing that to the table.

MM: What other pieces will be shown at “Infinite Indigenous Queer Love”?

JG: The works on paper are like this extended mashup. We had a bazillion stills we could pull from, so I was just like, “You know what? Like house music, I’m just going to start sampling my own history and kind of letting it tell a story.” I don’t need to make a new image. The goal of the paper works is to go back to what’s been made over the last ten years and expand on some of it, re-articulate it, re-introduce it. And then we’ll show a program of videos. One gallery will show the videos of the performances, and another gallery will show, I think, about four standalone videos that I’ve made over the last ten years.

MM: And the performances will be the ones from Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House?

JG: Exactly. So you’ll get to see the land acknowledgement by Indigenous Kinship Collective. You’ll get to see Laura Ortman’s performance. You’ll get to see Emily Johnson’s performance, and then the collaborative performance that Raven Chacon and I made, and then Eric-Paul’s and Luzene’s will come in rotation midway through the run of the show.

MM: I’m interested in the sensorial quality of your work, especially how the fringe pieces evoke movement. Could you talk a little bit about how an appeal to touch and movement comes through in your work?

JG: Well, I’ll throw something out there. In the public world, as Brown people, we’ve been told how to move. We’ve been told what is acceptable performance. We’ve been told when something is too “rez,” too ghetto, and I’ve been raised in that world. You have manners, you speak well, you get your education, you basically perform being white, but you’re always going to be Brown, so you’ll never forget it. And I think performance, for me, is just sort of like, “Oh my gosh, give your body a chance to talk. Let your body say what it wants and needs to say. Stop listening to whatever this performance is that you feel called upon to do and give other people the opportunity to do that.” And so that’s really, I guess, where movement comes from for me and the sensorial part of [my work]…

I feel modernism has tried to eradicate a sensorial experience of the world, and there’s been so many artists—creative people, thinkers, poets—who know that you have to experience the crappy things. You have to. You have to experience the salty and the sweet and the sour and the bitter. And this is the beauty of the world.

Mary McNeil is an Afro-Wampanoag Ph.D. candidate at Harvard University whose work considers space, place, and Black and Indigenous social movements.

Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House is on view at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum through June 1, 2022. “Infinite Indigenous Queer Love” is on view through March 13, 2022.