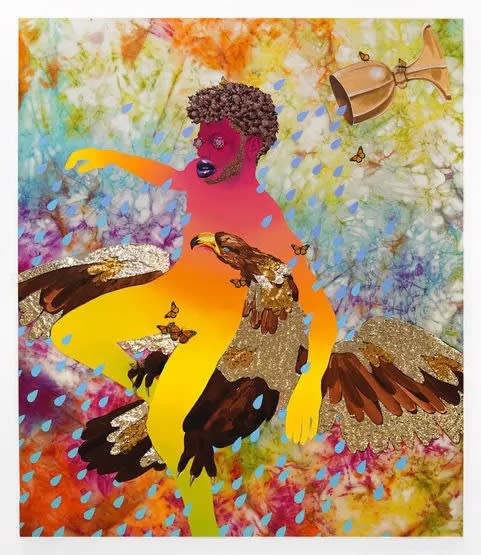

Devan Shimoyama's mixed-media work is an explosion of glamor, fantasy, and all things sparkly. From life-sized paintings awash with sequins and rhinestones to installations and sculptures filled with silk flowers and glitter, each piece accosts the viewer with bright colors and a total sense of extra-ness. In doing so he makes the Black queer body a site of beauty and desirability, while addressing the contemporary politics of both LGBTQ + communities and Black America.

Shimoyama was born in 1989 in Philadelphia and grew up with a love of drawing. He initially chose to study life sciences at Penn State University but after two and a half years he swapped his major to art and began exploring multi-dimensional painting. “I was pouring a bunch of different paints and seeing what was happening. I was playing with materials and figuring out how to prime surfaces for different types of marks. All of that was how I learnt how to technically make what I'm making now," Shimoyama recalls.

He went on to complete an MFA in painting and printmaking at the Yale School of Art, where he was awarded the Al Held Fellowship and felt ready to dive into the conceptual side of his work. The artist has always been attracted to studious environments because this is how he feels he can propel his work forward." I have always chosen places with an academic component because it helps me think in a more informed way," he explains.

"A lot of my work is fueled by reading-fiction, fantasy, prose, poetry. I wouldn't have known about that stuff unless I had a good education, "he adds." I remember a class in queer cinema that spanned from the 1920s to the 1990s, which was incredible. It meant reading Marlon Riggs and looking at how queerness can be buzzing un derneath the narrative structure that's on display. And then conversations with my peers, professors, and critics shed light on how these ideas would bleed into my mind and manifest themselves in my work."

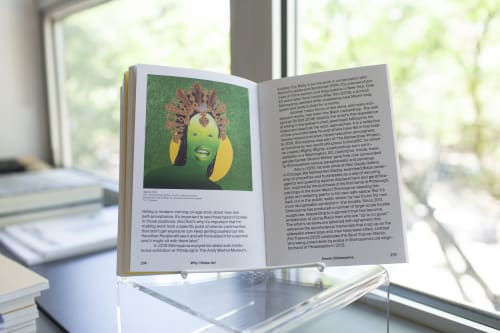

Devan Shimoyama, The Abduction of Ganymede, 2019. Oil, colored pencil, dye, sequins, collage, glitter, and jewelry on canvas, 84 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist and DeBuck Gallery.

This scholarly interest continued: straight out of graduate school in 2014, Shimoyama took a one-year visiting professor position at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, where he's since become Assistant Professor of Art. This position has afforded him the opportunity to develop his experimental practice in tandem with teaching." Moving to Pittsburgh meant I could make all the work I needed to make with ample space and time. I can clear my head and don't have to feel panicked or rushed. People might think you have to be in New York or Los Angeles, but many of my show opportunities have been through the generosity of the community here. When it comes to making connections, a lot of it has to do with being kind and receptive to people. Being genuine goes a long way.”

Shimoyama has exhibited extensively across the US including De Buck Gallery, Lesley Heller Workspace and Kravets Wehby Gallery in New York, Kavi Gupta in Chicago, Samuel Freeman Gallery and Zevitas Marcus Gallery in Los Angeles, Alter Space in San Francisco, and Emmanuel Gallery in Denver. Internationally he's shown at Kunstpalais Erlangen in Germany, Frieze London, and the Fondation des États-Unis in Paris, among others.

The artist has become renowned for his portraiture, whether of himself, his friends and acquaintances or what comes out of his imagination. He cites the rigorous conventions of old masters such as Goya and Caravaggio as influences, as well as Wangechi Mutu's fantastical collages and Kehinde Wiley's bright paintings. On his canvases , smooth expanses of color are formed from oils, acrylic, and pencil, while photographs may be used for eyes or mouths, accentuating these facial features. Then come the textural materials such as Swarovski crystals, fur, glitter, fabrics, and gemstones-demonstrating a magpie eye that was originally fostered by his grandmother's taste in costume jewelery, ritzy tablecloths, and best china.

Drawing from astrology, folklore, and traditional belief systems, orisha spirits and Apollo's Daphne come into view too, as do serpents-which for Shimoyama are not the cause of the fall but guardians of sacred realms. These figures often hang out in the background of his works, as in Dizzy Spell (2021), or coil around heads and shoulders, as in Sedusa (2021). "I'm creating my own queer Black male origin mythology," he explains." A lot of the materials I use are being imbued with meaning and specificity when they appear in the paintings. For example, black glitter represents the night sky, which for me is ripe for storytelling. The night is a time when there's a higher possibility for true magic moments to occur."

Another favorite motif is the teardrop, variously appearing as both physical tears and emoted rain. "I started the teardrops because growing up I never really saw Black men cry in a public way, or being allowed to feel in pop culture," he says. "A lot is being said creatively right now, but at the same time we're being oppressed from the top so there's this friction. It's intense. People are not very open to saying how they feel."

An early series of paintings was inspired by those of Shimoyama's musical heroes who use the language and cultural codes of queerness without explicitly presenting as gay. "Johnny Mathis came out and was then threatened back into the closet to continue his career. Frank Ocean made an open statement about having an intimate relation ship with another man but doesn't identify as gay. Prince was super glam and benefited from all of that. I'm interested in those who are othered in that way but don't fully engage with it in order to have success. And I'm waiting for that moment when it can be from the beginning, when we don't have to hide."

For the artist, the 2017 film Moonlight was a watershed moment. It was the first time he'd seen a Hollywood movie that represented his lived experience in so many ways. "It's an all-Black cast. It's not about slavery or servitude. It's a LGBTQ film that's not about AIDS. And it's not just scary dudes standing on corners with guns. They're telling a modern coming-of-age story about love and self-acceptance. It's important to see those types of bodies in those positions. And that's why it's important that I'm making work from a specific point of view so communities that don't get exposure can keep getting pushed out into the ether. People will see it and will think about it for a second and it might sit with them later."

Devan Shimoyama, Akasha, 2021. Oil, colored pencil, glitter, acrylic, costume jewelry, rhinestones, and collage on canvas stretched over panel, 72 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2018 Shimoyama enjoyed his debut solo institutional exhibition at Pittsburgh's The Andy Warhol Museum Entitled Cry, Baby, it put his work in conversation with Warhol's Ladies and Gentlemen (1974-75), a series of portraits of trans women and drag queens in New York. Over 40 years later, here comes Miss Toto (2018), a portrait Shimoyama painted while shadowing said Miami drag queen and body builder for a month.

Another major focus of this show, and many subsequent works, has been the Black barbershop. The self portrait Sit Still (2018) depicts the artist's first experience of sitting in the barber's chair, jewel tears falling into his iridescent beard as the razor approaches. It is a reflection of how uncomfortable he and others have felt in this tradi tionally heteronormative, hypermasculine atmosphere. In 2019, Shimoyama was part of The Barbershop Project, an initiative by non-profit arts group CulturalDC, for which he created Mighty Mighty, a barbershop-cum-art installation in a Washington, DC, parking lot. Inside, transgender barber Brixton Millner gave free cuts surrounded by Shimoyama's riotous paraphernalia and paintings.

Also in 2019, his solo show at Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago, We Named Her Gladys, examined Black ownership of properties and businesses as a way of securing agency and guarding against displacement and gentrification. Inspired by the purchase of his first home in Pittsburgh, paintings in the show depict Shimoyama weeding the grass and watering plants in his own safe space. But it's back out in the public realm where he has found his now most recognizable symbolism-the hoodie. Since 2017, Shimoyama has produced a number of large-scale hoodie sculptures, responding to a garment that has become emblematic of young Black men who are "up to no good." The artist's versions are adorned with ephemera that reference the spontaneous memorials that crop up on the sidewalks where boys and men have been killed. Untitled (For Trayvon) (2021) celebrates the life of Trayvon Martin, who was gunned down by police in Shimoyama's old neighborhood of Philadelphia in 2012.

Taking this thinking further, his site-specific installation for FUTURES, the 2021 exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, imagined a monument to the tumult brought about by racial violence and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The Grove, with its crystal-covered pillars surrounded by glistening sneakers and flowers, offered up an exuberant forest within which visitors could pause, forgive, and heal. As with all of his work, Shimoyama is bringing his audience to the intersection of Blackness and queerness to bear witness and to see the light. It's not difficult to see how the rage, alienation, and grief could be all consuming, but for this tender artist the end goal is always joy and always love: "I've no interest in making a bunch of sob story paintings. Or showing Black men in pain or grief as a singular emotion. It's not all they are. My paintings are super glamorous and celebratory-they're directly confronting the viewer and engaging with them, posing and gesturing to them, inviting them. It's important to make it an open story."