Tomokazu Matsuyama was born in Takayama, Gifu Prefecture, a large but sparsely populated city in the midst of the Japanese Alps with a rich history of kimono-dyeing, ceramics, and lacquerware. But the artist's earliest creative memories are set further afield, in Orange County, California. After moving there with his parents and older brother when he was eight years old, Matsuyama was enchanted by the city's emerging skate scene and graffiti, as well as the DIY esthetic that surrounded them both.

"Those skaters-slash-artists influenced me a lot," he recalls. "Coming from the middle of nowhere in Japan, being exposed to that culture was quite a shock, which wasn't bad at all, actually. One of my mom's friends was dating John Grigley, one of those early pro skaters who did their own skateboard deck design. I would go visit them with my mom, and they would give me random sketches.

"I was always trying to copy those skate decks and those influences that I had-not that I think that was any type of artwork or anything. It just very naturally grew, and I kept drawing and drawing."

Matsuyama only lived in California for three and a half years before returning to Japan, but when he did, he had "pretty much become an American kid," bringing with him a stash of Bones Brigade T-shirts, heavy metal cassettes, and an interest in drawing and skateboarding. But transitioning back to life in Japan wasn't always easy.

"Japan is so isolated. There are really no neighboring cultures, it's surrounded by the sea," Matsuyama says." It was hard going back and readjusting myself after being in LA and becoming a different kid, because we were living in a very conservative part of Japan. They don't have this rule at schools anymore, but at the time you had to have one of those buzz cuts, and all the uniforms looked like military uniforms. You needed to wear a helmet to get on a bicycle. It was full of restrictions. On top of that, there was no one else who had returned from another country. So I did get picked on pretty hard for just being a little different."

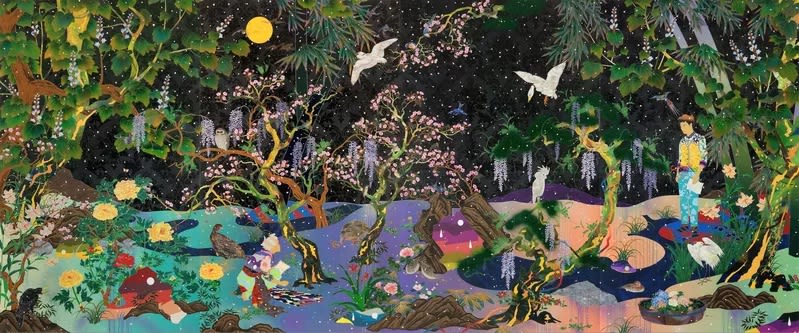

Tomokazu Matsuyama, Beautiful Stranger Beyond the Sunshine / Nothing's Burning Underground, 2018. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 67 x 105 x 1 1/2 in. / 68 x 105 x 1 1/2 in.

Making the most of Japan's mountain ranges, Matsuyama shifted his interest in skateboarding to snowboarding while in high school. But academics became a primary focus. His parents enrolled him in a Tokyo boarding school where he had a "classic 'study-for-ten-hours a-day' Asian education," he explains.

After graduating, Matsuyama enrolled as a business management major at Sophia University in Tokyo, which his older brother, who also attended, told him was the easiest course of action. The program was flexible enough that he was able to take a year off to pursue a career as a snowboarder between his junior and senior years, after finding a brand sponsor. ("When it comes to college in Japan, you just have to study until you get in. Once you get in, you have four full years of freedom," he explains.)

"I wanted to see how much further I could take snowboarding, and I came to the US to attend snowboarding camps and do some shoots. By then, I was becoming somewhat of a semi-professional snowboarder," he explains.

When he was 21, Matsuyama broke his ankle while training. The injury required surgery and stopped him from walking-let alone snowboarding-for 11 months, at which point he decided to recalibrate again.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, We Met Thru Match.com, 2016. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 100 x 240 in.

"I realized I would probably be able to do this for several more years, if I was lucky, but not longer than that. I was still going through this business management degree, but I thought that creating something visually, which I've always enjoyed doing, was something I could do my entire life. So then, still being a little bit realistic, I decided to pursue graphic design. While I was in my last year of college, I didn't do any corporate job interviews. I decided to go to this night school program to see how graphic design is, and I got really attached to it."

After finishing his business management degree in Japan, inspired by the artist-skaters he encountered in LA as a child, he reached out to his contacts for work." I took all of the artworks I created to the sponsor that I used to ride for and all these magazines that I used to be featured in. They would give me these projects...A year or two later, I actually became a creative director for one snowboard company, and was in charge of doing all the decks, ads, apparel lines, and stickers. Everything. So that really became an outlet."

In the early 2000s, Matsuyama relocated to Brooklyn, where he's still based today, to pursue an MFA in communications design at the Pratt Institute, living off his income from the

snowboarding industry.

"I still remember meeting some fellow artist friends of my generation, maybe a little older, who were quite active, like KAWS and José Parlá. This group of artists really influenced me. I was like, 'Wow, becoming an artist is an option in life.' So I finished my studies at the Pratt Institute in two years. I remember that by the time I had finished my first semester, I kind of knew that I wanted to become more of a fine artist," he says.

"That was when a lot of galleries were starting to pop up in Chelsea," he continues." I really wanted to see how the contemporary art world functions, and I was very lucky to become an assistant for this one painter who then I think showed at Paula Cooper. His name's John Tremblay. He was a minimalist-well a lot of artists at Paula Cooper are minimalists-which is kind of rich because it's pretty much the opposite to what I do now. But he had a couple of assistants and I saw the work and that was a big influence. I was there for maybe four months-I helped him for a big show that he was prepping. That made me want to step into where I am now."

Today, Matsuyama is known for colorful, often collage-like paintings that respond to his experiences navigating between Japanese and American culture. He has drawn inspiration from both sides-from Jackson Pollock, Pop Art, and graffiti to manga, the Meiji era, and woodblock printing-often merging Japan's historic focus on decorative art with Western conceptualism.

Rather than playing up the geographic and esthetic differences between his two homes, Matsuyama emphasizes cultural hybridity in the age of globalization: "I don't like the term' East meets West.' It's more 'East is West.' I mean, come on: If you circulate through, they go the same direction" he explains. "It's so naturally, kind of organically, blended together that the boundaries are really not there.

"It comes down to patchworking different esthetics," says the artist, who has referenced works from the likes of Picasso and Hokusai, as well as abstractionists Sarah Morris and Sam Francis. "If I incorporate several different masters within one work, it looks like it's none of them, you know?"

Music has inspired his sense of hybridity as much as his own bicultural upbringing: "I got the idea from sound producers sampling a lot of different notes. I could use the term 'readymade' or 'appropriation', but it simply came from the type of music that I listened to," he says.

If Beastie Boys and early hip hop sparked his appreciation for sampling, living in New York accelerated it." Being in New York, you just meet everybody really. You meet DJs, musicians, rappers, composers. That's when it really came down to mish-mashing everything. Everything has its own beauty, and it just naturally led to this kind of a mess."

Like skate culture, with its emphasis on DIY, music has provided Matsuyama with a model for what can be achieved when an artist looks at boundaries as fluid rather than fixed. "Musicians are so translucent in the way that they shift from one genre to another. It's just so free. When I first stepped into the contemporary art world, there was a lot of 'You can't do,' 'You shouldn't do.' There were so many rules," he says. "But I think those rules are becoming looser and looser. People are getting bored of being told what you can and can't do."

This is especially exciting for an artist like Matsuyama, who has not only blurred the limits of genre but also the definition of what constitutes art-something he first observed from the skaters who could turn stickers, T-shirts, and pins into bold artistic statements, but also in his own Japanese culture, where folding panels and teacups could be considered masterpieces. Though fine art remains his focus, Matsuyama has also done collaborations making artwork for snowboards, skateboards, clothing, and toys.

"When I see art in the West, it's really about authorization, right? It can only be 'art.' Whereas in Japan, the most valuable, the most highly thought of art was always utilitarian art," he said.

"I can still create a T-shirt, but I can also make these massive paintings that go on to a museum. And I think that is what makes our generation interesting and unique: pretty much anything could be artistic these days."