When Inka Essenhigh was a child, she didn't have pop stars on her walls. Instead, she had posters of paintings: Van Gogh's Almond Blossom (1890), Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), and Picasso's Bouquet of Peace (1958) among them-what the artist fondly calls "the greatest hits."

Essenhigh's own greatest hits could perhaps be more readily compared to other canon-forming artists' painter's dreamlike works draw as much on science fiction such as Dalí and Magritte. The renowned New York-based tion, myths, and fables as they do from the formal tenets of Surrealism, to imagine epic scenes of both bucolic plenitude and the urban sprawl. At once otherworldly and close to home, idyllic yet disturbing, Essenhigh's atmospheric spaces don't so much provide an escape from reality as bring forth the unseen within it. "I respond to things that are a fantasy, but I don't see it as an escape-I see it as part of how we inform how we're going to move forward," the artist says.

"I can't remember a time when I didn't want to be an artist. There was never a plan B," she recalls of her early years, first in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania (where she was born in 1969), and then in Columbus, Ohio." My mom got me extra art tutors and bought me art books-Mary Cassatt, Georgia O'Keeffe. We'd go to a lot of museums and I liked the old masters."

She puts this level of encouragement for an uncertain and hard-to-follow career path down to her maternal family's difficult history." My grandmother painted, she was from Ukraine and came to the US as a refugee from World War II. Sometimes it's been said that when you're a child of immigrants, you're trying to take back status, and my mom was very snotty like that. On some level, she wanted me to have a status that couldn't be taken away."

Soon enough, an interest in music began to influence Essenhigh's tastes. She was drawn to alternative rock and goth, the visual culture surrounding subcultural bands such as 'Til Tuesday, The Pixies, and Love & Rockets, which speak to her appreciation for the intense and hyperbolic. "I really loved old-fashioned painters, so maybe goth appealed to me because it has something to do with a history, a romanticism. I can't say I looked at album covers and thought,' I want to be like that,' but it informed how I went through life in that you were supposed to be questioning of The Man. You were supposed to be impassioned, go all out, be completely sincere and unashamed. Also, with punk and goth there's a show and there's costumes that can go into fantasy, which I obviously respond to."

She received an undergraduate scholarship to study at Columbus College of Art & Design, where she enjoyed a relatively traditional education, taking in everything from printmaking to ceramics." I knew you were supposed to be an Abstract Expressionist, but I was scared of that. I didn't really get it. The local art school had a program that was Bauhaus related. It gave a foundation in figure drawing and color theory. I felt much happier going down that road. And it's still with me today. I think of it as wearing a badge of honor, but also of provincialism. It's my Midwestern-ness that makes me want what I make to be good.’"

Essenhigh earned an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York, graduating in 1994 and going on to form part of the generation of young artists in the city that led the contemporary return to figuration, alongside the likes of Rachel Feinstein, Will Cotton, Lisa Yuskavage, and Cecily Brown. Her early work was dubbed Pop Surrealism, and she was part of the influential 1998 show of the same name at Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Connecticut. At that time she was leaning into cartoon-like forms and simple colors realized in enamel on canvas to create slick, bright, and flat surfaces that had an insatiable viscosity. She also established a forceful breakdown of perspective, putting the viewer up into the air as if floating above the scene at hand, adding another element of intentional oddness.

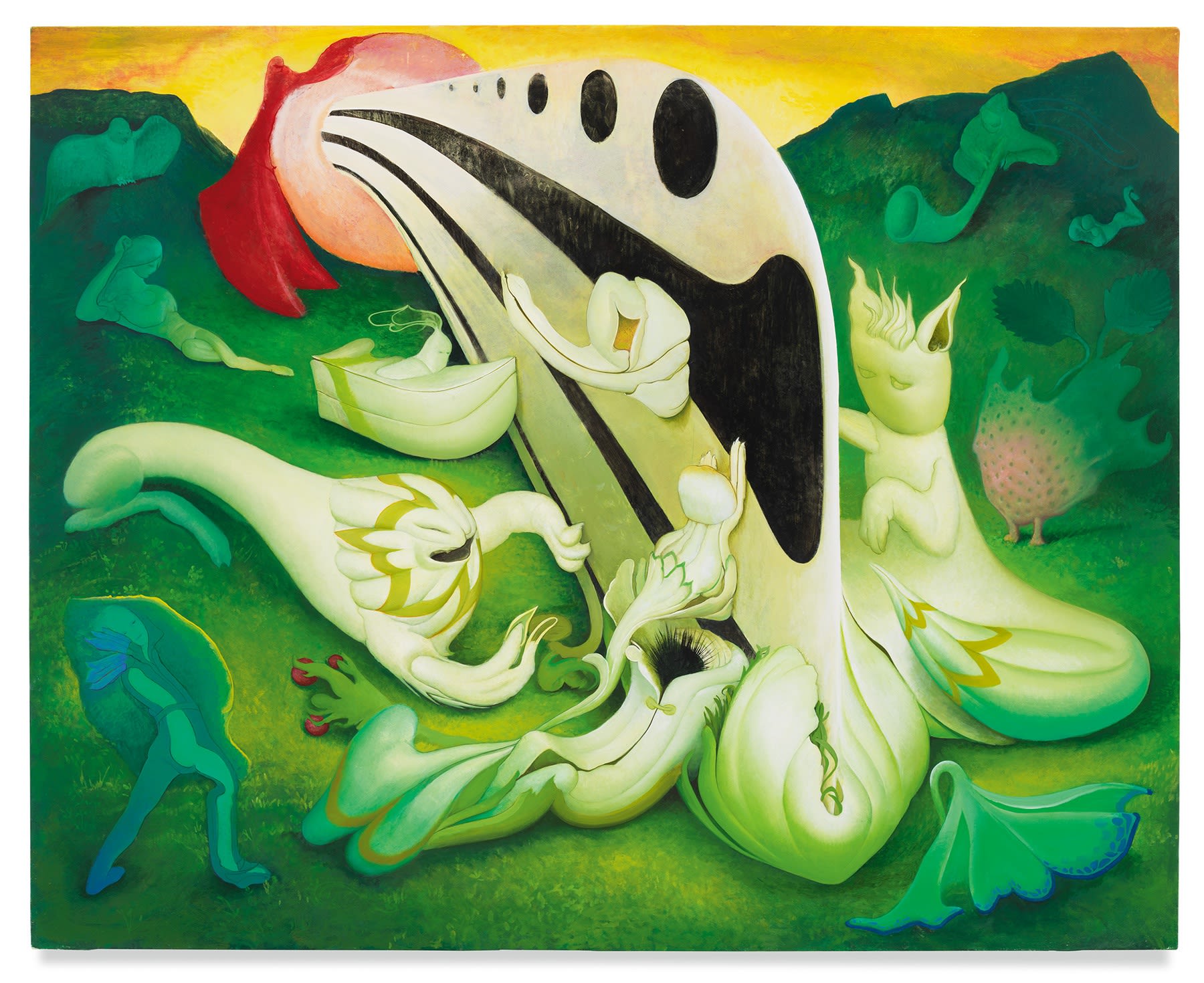

Inka Essenhigh, Dawn's Early Light, 2019. Enamel on canvas, 40 x 50 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Over the next decade, Essenhigh continued to rise in prominence and in 2007 was included in another landmark show, Comic Abstraction: Image-Making, Image-Breaking, at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC. More recently, her solo exhibitions include Miles McEnery Gallery in New York; Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago; and MOCA Virginia, Virginia Beach.

She's now represented by Victoria Miro in London, and her work is also in the collections of major museums including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, Denver Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami, MoMA PS1 in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Seattle Art Museum, the Tate Modern in London, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

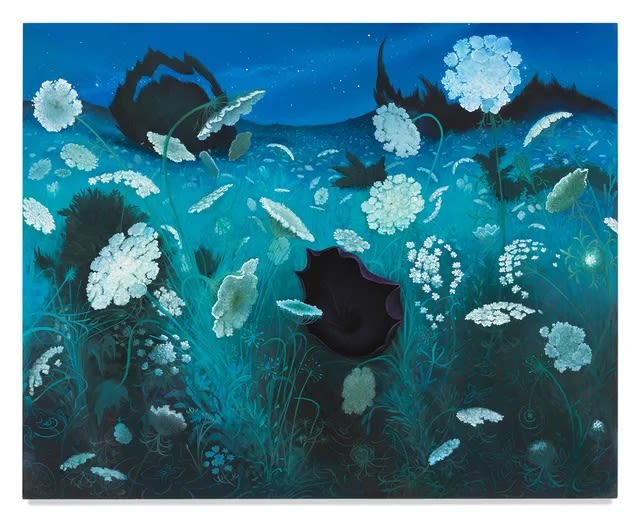

Inka Essenhigh, Queen Anne's Lace, 2020. Enamel on canvas, 40 x 50 in. Courtesy of the artist.

"There's something about the city, it's a stage," she reflects of New York and of her success there." You can walk down the street and run into the person you need to run into. And when the time is right, it feels like your work can go down to the center of Manhattan like a chiropractic adjustment and, after that, it can go everywhere all over the world, all at once. And it still has that ability today. I mean, New York sucks to live in, but it still can do that. Not a lot of places can. Somehow, it's too diffuse elsewhere. But here there's an alignment to the whole thing."

Essenhigh still occupies the same Lower East Side studio space she shared with two artist friends and her then boyfriend, now husband, realist painter Steve Mumford, straight out of grad school." Back then we all made a pact that whoever we managed to drag back here to the studio, we'd show them all of our work. That was the goal," she remembers fondly." The idea was that, even if they didn't like your work, we'd all be better off if they liked your friend's work. And it paid off because I think the way people come to your work as a young artist is through your friends. What's the vibe, what's the scene, what are you talking about?" She misses the frisson of those early years but does not underestimate the value of being more assured in her own skin, especially in an industry driven by trends and market forces." One of the problems of aging as an artist is that you lose your context, and then people don't know how to place you. But going forth, the story changes. It doesn't have so much to do with anyone else out there. You become more you. And it becomes about whatever the truth is for you. Whether you want to be ironic or sincere, you have to find the path. Now when I see a work that's great, I won't want to crib a mood or jump on board. I just enjoy the fact that that artist figured it out and I will figure it out differently.”

Throughout her career, Essenhigh has displayed a healthy disregard for consistency by changing up her materials (from enamel to oil and back again) and esthetics to best suit her ceaseless quest for originality. While her work is clearly steeped in an in-depth knowledge and care for both art history and pop culture, she is not interested in using exact source materials. Hers is a fusion of figuration and abstraction, landscape and narrative, all drawn entirely from her imagination." There are no sources. It's totally invented. I have a good visual memory and feel like I can sense when things are cribbed. And there's nothing wrong with that but what I'm interested in is looking for the new. I have tons of art books and get them out at different times, but more just to prop me up and tell me, It's OK! I need voices to say, 'You can do that, it's legal.'"

In keeping with Surrealism's championing of the unconscious and rebellious mind, for a long time Essenhigh relied on automatic drawing, applying initial brushstrokes intuitively that imbued her work with a liberated fluidity.

Then, through a process of free association, a story would unfold to her, steeped in symbolism and observation. Myriad interests are apparent, ranging from Greek and Roman mythology, such as her paintings Daphne and Apollo (2013) and Diana (2010), to fairy tales, anime, and graphic novels, as can be seen in Stubborn Tree Spirit (2012) and Green Goddess II (2010). She has long embraced disquieting fairy and god-like beings, but they are as likely to pop up floating in a moody, blackened sky or riding a green ocean wave as they are to be downing drinks in a Midtown bar at happy hour or spicing up the subway at rush hour.

Indeed, her adopted home has proved a strong and recurring playground in her work. The way a golden sunset hits Seventh Avenue just so can, for Essenhigh, turn the West Side into an anthropomorphic, moving being, as depicted in Manhattanhenge (2018). Her site-specific work at NYC's The Drawing Center presented a posturing stand off between the city's classic cast-iron façades and the shiny, glassy newcomers on the block.

"One thing that is a constant is that it's got to be new. I'm looking for a way forward," she explains of her shape-shifting sensibilities." I do have a recognizable touch. It's a gift to do something that looks like my work no matter what I do. So, I've given myself full permission to abuse it and have made a lot of different types of work. For some people it can be confusing, but the problem with sticking to one thing is that your truth can change."

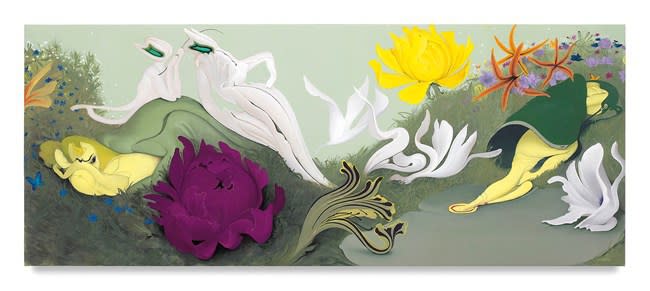

Inka Essenhigh, Midsummer Night's Dream, 2017. Enamel on canvas, 32 x 80 in. Courtesy of the artist.

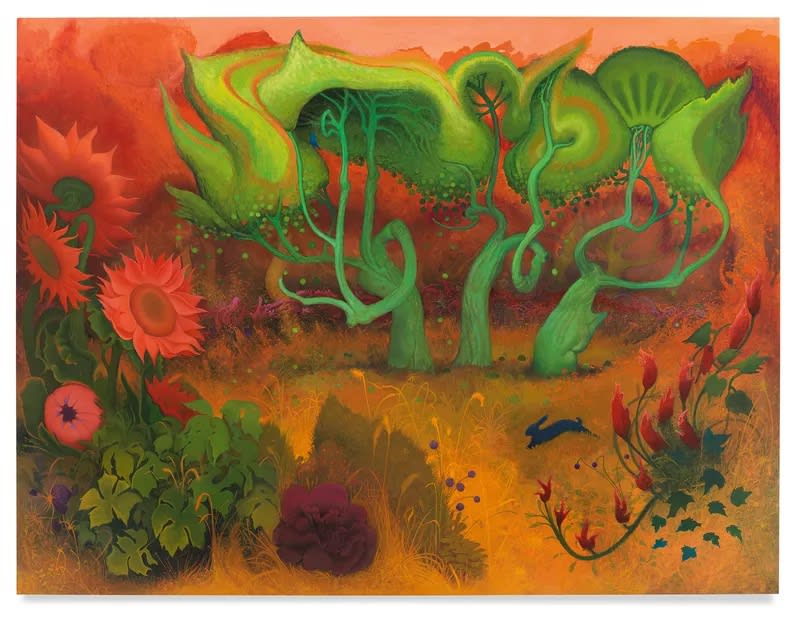

More recently, Essenhigh has moved away from both the cityscape and automatic drawing to focus on a natural world steeped in heart-melting perfection. For Uchronia, her 2019 solo show at Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago, she created a pastoral utopia that reminds us of our own fast-fraying coexistence with our planet. Each painting presents a vision of a potential future, filled with faun-like humans and luxurious vegetation. In Welcome to the Gather-n-Hunt, a Family Restaurant, 3500 CE (2018) we step into an eatery mimicking the lifestyle of our Mesolithic ancestors. In New Jersey 2600 CE (2019), living creatures are absent but the golden underground domes they inhabit remain, surrounded by huge blooms in accentuated colors. And in Fragments from a Nature Cult, 2087 CE (2019), we see elements of what's left from an ecological movement we could only dream of in the present day. Are these glimpses of an idealized yet plausible tomorrow, or realities that what will only come to pass once our current epoch has achieved extinction? Either way, the works are not meant as portals to abscond from reality. On the contrary, they're the change she wants to see.

"It's not escapism," the artist says, referring not just to this series but to her work more generally." My husband used to go to Iraq during the war to make art about it. That's when I started to withdraw even more into my own imagination. I always wondered if this was escapism, and it may have started out that way, but for me it's the only way to create change in the world. To give an obvious example, can you imagine what peace might actually be like? It would take all of your imagination to work out what that might mean for you, and you'd have to experience it on some level if it was something you wanted to bring forth in a painting. So, on an unconscious level, it becomes a possibility."

Essenhigh's 2021 exhibition at Victoria Miro Venice ventures further still into an arcadia-like land with an entire focus on flower paintings. Here, humanoids disappear altogether, now personified as botanical forms. Based on real flowers, her flora and fauna are amplified to take on an animated and spiritual energy not found on an animated and spiritual energy not found on this planet. These are luminous organisms ripe with personality, their saturated colors lit by a heavenly source. In Bleeding Hearts (2021), erotic blooms in a vase drip with baby petals. In Blue Field (2021), flowers become galaxies, black holes, and hero characters in their own right, her fine, suggestive lines quivering with potency and divinity.

It's Essenhigh's willingness and ability to indulge in beauty and let go of reality that sets her apart from much of the contemporary art world. And she's well aware that playing with imagination could easily be seen as kitsch. But the artist argues that the fantastical realm has given the world more pause for thought than it's often given credit for. "I bump up against taste a lot. But if your definition of kitsch is something that's fake, a feel-good trinket, then there's so much abstract kitsch out there that means more to me than a lot of figurative paintings today. I would hold that Frank Frazetta is more original than most living painters."

Essenhigh readily admits she has" an axe to grind" on this topic. So, when it comes to her own work, she is resolute in her mission to forget about tired arguments of high versus low and, as always, let her intuition guide her." Fantasy paintings of fairies and imagined spaces aren't edgy. Sometimes I want to eliminate unnecessary edge, and that can be a really uncomfortable place for people in the New York art world. But I want to find something that feels good. When I was younger, I wanted to have that raw, hitting home thing. But then I questioned that. Why does art have to be gut wrenching to be important? I think there's something else that a work of art can do. If you don't like your world, you can look at a painting that's more chilled out and that will help you to deal with it."

Inka Essenhigh, Orange Fall, 2020. Enamel on canvas, 72 x 96 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Going further still, the artist sees her practice as moving way beyond getting in the zone. It's a deep dive into her own self where the line between real and unreal, or even you and me, becomes entirely blurred." It's hard for me to talk about because it can seem so meaningless to use words like 'surreal' or 'collective unconscious.' William Blake would call it 'the realm of the true imagination.' I don't have a better way to describe it than that, but sometimes I feel like I can go into an imagination that has a physical-like aspect to it. It can physically alter me."

While she does not pretend to believe that the viewer of her works will necessarily experience or even understand them in the way she might, Essenhigh does think that the ultimate measure of a painting's worth is its ability to let you in, to see beyond it, and to feel. This is a quality she looks for in other people's work as much as her own." Some artists have a beautiful touch and I love how they move paint around. But if you couple that with something that they're bringing through from the unconscious, that's what really does it for me. That's when a painting I'm looking at feels genuinely sacred. It's a moment that passes through you for a split second-and then it's gone. Your critical brain takes over and breaks it down. I can even doubt myself that it happened." Putting it another way, and coming back to the idea that art should lead you towards the light, or even just make you happy, Essenhigh hopes her gut is now finely tuned to that higher frequency." There are so many ways a painting can talk to you. One way is that it can make your eyeballs soften so that you can drink it in. There'll be a quality to the creativity of the work that has nothing to do with the content, and when you see that it has that thing, your whole body gets drawn forward and relaxes. I've come to trust those sensations more than my brain."