With her large-scale works of women in repose, Mickalene Thomas is ensuring Black women are seen in the insular world of fine art.

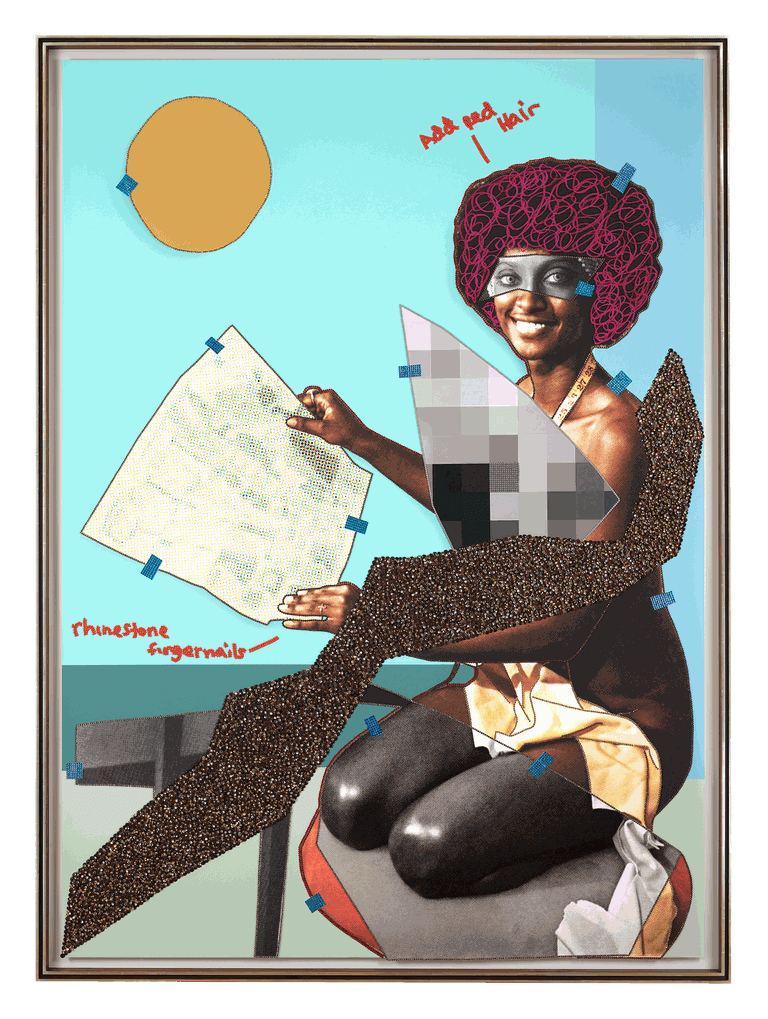

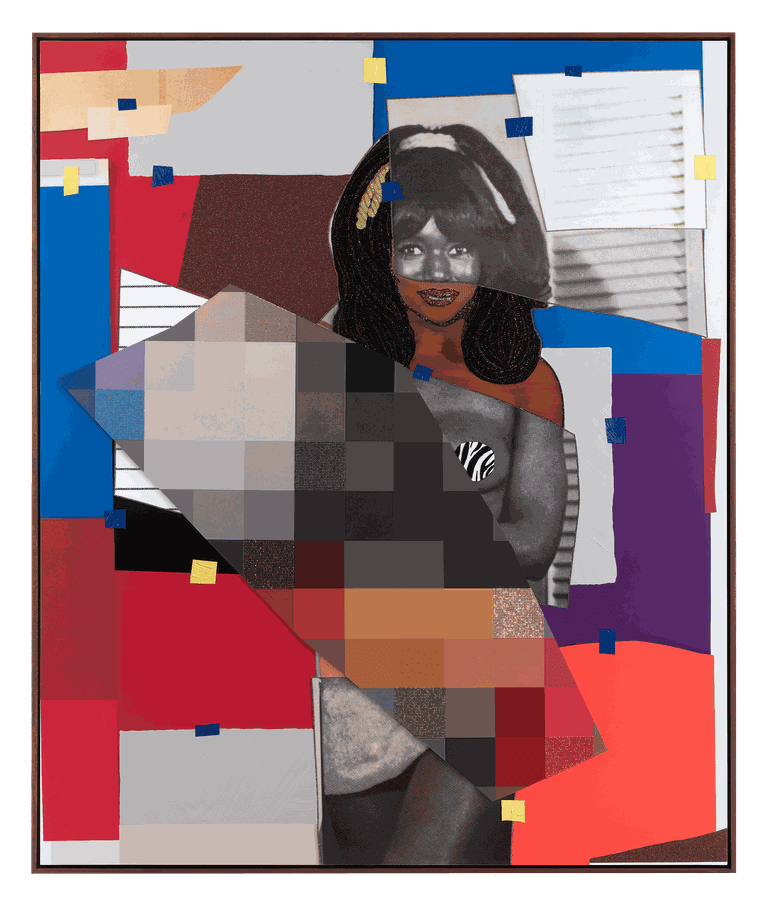

Known for creating large-scale paintings and collage portraits that depict bold images of Black women in lush settings, contemporary visual artist Mickalene Thomas is having an equally outsize impact on the art world. In a space that has historically associated beauty with notions of Whiteness, Thomas has dared to paint Black women and their lives as aspirational, beautiful, and abundant.

Thomas’s installations of collages, video, and photography have been viewed globally and added to collections at art institutions around the world, making it possible for Black women to see reflections of themselves and their desires in venerated public settings. “When they go to a museum they can see that there's a conversation of beauty that exists that is not conventional,” says Thomas. “So it inspires young women to feel proud about who they are.”

Behind the artist’s visionary mission was a very relatable muse: She first turned to her mother, Sandra Bush, for inspiration. Thomas’s Black bodiespay homage to the six-foot-one model-esque matriarch and Thomas’s childhood in Camden, New Jersey, during the 1970s. “She was my biggest cheerleader, fan, and collaborator,” says Thomas. “When she walked through a room people, would be drawn to her light and beautiful spirit. She always had all types of friends from different backgrounds. Caucasian, Asian, Russian. That was her world, and the one that she brought my brother and me up in.”

Not long after Thomas’s mother passed away in 2012, the artist began work on the first of her groundbreaking solo series at the Brooklyn Museum, “Origin of the Universe,” a body of work that explored “Black female beauty and sexual identity while constructing images of femininity and power.” The powerful works have earned her a prominent spot in what the Smithsonian referred to as a “new wave of contemporary art, a movement that reimagines established images of beauty in the art canon.”

Recently, the revered creator gave us a peek inside her mind, explaining her innovative approach to art and activism.

Your art is reshaping the field. Can you share your unique process?

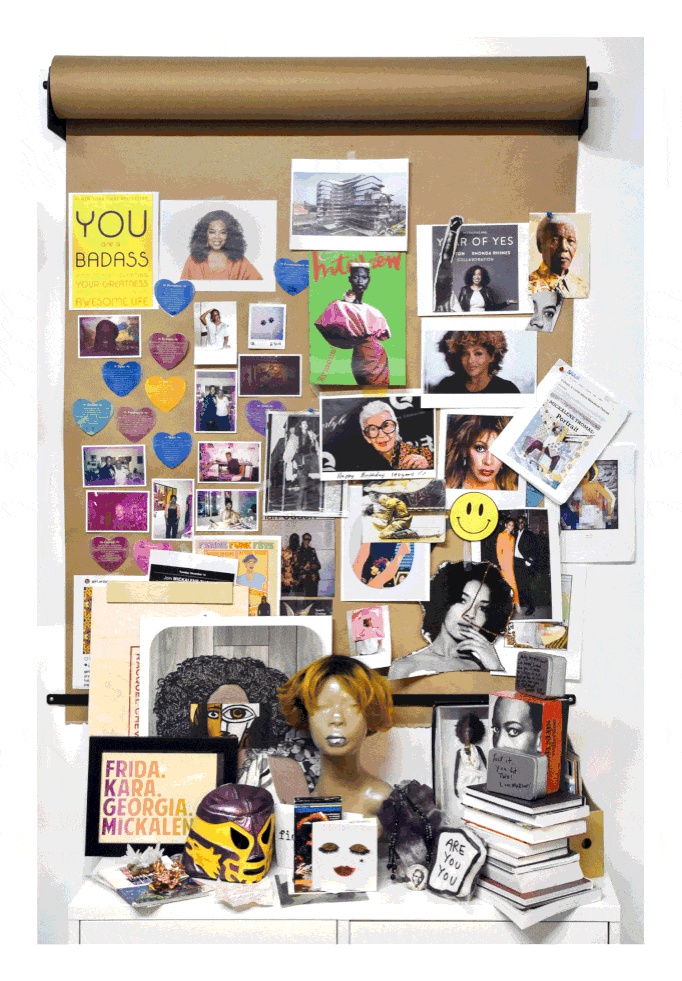

A lot of my work begins with the ideation process, because what happens prior to even sitting with the blank canvas is part of bringing the artwork to fruition. Doing the research and experiencing the excitement around it entices and drives me and allows the aha moments. I go online and create Dropbox folders and start downloading images and collecting all these pictures. It starts with acting on those ideas through research. And also by reading, because maybe there’s literary support around that. Then I start to think, Do I want to just use the archival images, or do I want to create my own resources by doing a photo shoot or reaching out to people? I also see if maybe there’s a documentary related to my subject. And I make a list of things that I’m thinking about, which propels other ideas.

So it’s not necessarily like one idea immediately leads to the execution...

I’ll make a series of collages. Sometimes it’s with the same image. I’ll print out photographic images and start making this sort of body of work through collage by [changing] the composition, the color, and the texture. And while I’m working on those collages, I’m thinking of how I want to execute it in the painting. And then those collages become their own bodies of work. I tell my students, “You can work out everything on your canvas, or you can work everything out before your canvas,” so when you get to making the work, you’re just freely making the work. There’s not so much struggle or pushing through. For my process, I like that a lot of the struggle comes before going to the canvas. That’s not to say that even when I’m painting or making the image on a canvas, things don’t change.

Your images of beautiful Black women have enriched the art world. Can you also share some of the other ways you’re helping to empower women in the field and impacting the business?

I’m one who always has created a support system for emerging queer artists by creating different platforms like Pratt Forward, which I cofounded with Jane South, the department chair of painting at Pratt Institute. This is a mentorship program that provides practical business strategies for artists’ careers. I also cofounded Deux Femme Noire with my partner Raquel. This platform helps artists of color and women queer artists to pursue their creative endeavors, whether it’s for an exhibition, a show, a special project they’re doing, or just particular advice about contracts and relationships with galleries.

"It's a huge impact for artists of color to know their worth. That's what I want to be part of my legacy."

-Mickalene Thomas

I think cofounding both will create very intelligent, strong artists who have a great sense of both the creative and business sides of their practice. One of my students called me up and said, “You know, you doing that class of artists in the marketplace was one of the best things we’ve had at Yale. And I’m so happy that you were there.” That just shows that what we’re doing works, because the business of art is not taught in schools. It’s integral to what they’re doing. It really does make or break the success of most artists if they don’t have that support system or knowledge. It’s really important for me to create a foundation for these artists so they know that they’re not alone in their endeavors. And it’s a huge impact for artists of color to know their worth. That’s what I want to be part of my legacy.

How do you see women’s place in the field?

As far as women and art, we’re doing it. There are more women artists than there are male artists. And as we get into the positions that women are filling now as art historians, as curators as directors, I think the more we do that, the more…institutions like museums will know that we are just as valuable as our male counterparts and worthy of major mega shows like Andy Warhol. We could generate the same population and audience as these male counterparts.

What’s next for you, and how will it shape the future of the art world?

One of the things I’m working on right now is Black beauty pageants. After spending a lot of time working with the JET beauties of the week, and the JET calendars, I decided to take it to a different level and really figure out this space of pageantry and how, within our communities, we’ve carved out that space. There was a lot of non-inclusion in the mainstream pageants like Miss America. So we had to create that space for ourselves, and there was this community that was built up and all these women that went through that trajectory of where they are today. And so for me, it’s very exciting to start there.

What is your vision for the future of art?

One of my visions for the future of art is that there will be a visual artists’ union—we’re the only creative field that doesn't have a union—so that we are all recognized and we’re at the top of the pyramid. Without us, there is no art market. Artists need to understand that they are leading and driving the market by how they participate in it. And that the galleries, the collectors, the museums aren’t the only ones that are dictating what the market is. We have to recognize that our voice and our action and what we’re doing is also a larger part of that. And that goes back to being, knowing, understanding what it means to be at the top of the pyramid. Understanding their value and their volume.

I think because the world has changed, we have allowed inequities to enter the art market, and this shift has occurred in how artists are paid. I believe that artists will rightfully start getting a percentage of residuals from secondary markets. I think the door has been opened, and there’s a great opportunity for that to change.