Seeing the Toronto Biennial of Art through my daughter’s eyes helped me push past some of its challenges by experiencing it on a primordial level.

TORONTO — As a new mother, I have craved every minuscule second of freedom I’ve gained by my six-month-old daughter’s wake windows becoming longer. Between feeding and a nap, I can now squeeze in up to two hours of art viewing.

The logistics of a biennial, with or without a six-month-old, require baby-tracker-app precision. Multiple exhibition sites in a day? Forget about it. That block of dense wall text? Sorry, mommy brain. I’m exhausted and sleep deprived, with no time for slow art experiences. If it doesn’t move me, the stroller and I roll onward.

Seeing the Toronto Biennial of Art through my daughter’s eyes, then, helped me push past some of its challenges (more on that later, but there’s a haze of cautious, overextended curating and interpretation) by experiencing it on a primordial level. Because two hours, minus a diaper change, travel, and the potential meltdown, becomes more like 30 to 45 minutes. So for the sake of this essay, let’s consider this my “embodied perspective,” however frazzled and distracted that might be.

Installation view of ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᔪᒻᒪᕆᒃDouble Vision: Jessie Oonark, Janet Kigusiuq, and VictoriaMamnguqsualuk

Yet I believe this biennial, entitled What Water Knows, The Land Remembers, welcomes this slant. Its curatorial thinking seems conceptually aligned with kinship and artistic lineages found and inherited. Rooted in the ecological mapping of the city’s waterways, this flows into a greater two-part framing informing its more land-focused 2019 edition. A curatorial team led by Candice Hopkins (Documenta 14, SITElines) is committed to highlighting the work of Indigenous and female contemporary artists who employ traditional craft as a minimalist (or maximalist) strategy for centering personal narrative. But a lot of these significant works are diluted by their endlessly documented process-based methodologies, or worse, diminished by the institutional virtue signaling.

I’m getting ahead of myself here, though — I promise to see this through my daughter’s eyes. Right now, she’s really into colors and shapes (LOL, I know, which baby isn’t), so she was entranced by the technicolor saturation that was Jeffrey Gibson’s solo installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto (MOCA). (MOCA is one of the participating institutional partners. Many of the Biennial’s most substantial projects — Lawrence Abu Hamdan at Mercer Union, Eduardo Navarro at High Park’s Colborne Lodge — were its solo co-commissions.) The Mississippi Choctaw/Cherokee artist’s I’M YOUR RELATIVE wallpapers the MOCA’s lobby interior and patio exterior with pseudo-wheat-pasted posters and stickers of Navajo and Huichol-style patterns and decolonization slogans, filtering craft and abstraction through a street (or social media feed) vernacular. Throughout the space, people can sit in cushioned, cubby-like pods; younger visitors are encouraged to read inclusive picture books stored on the pods’ bottom shelves. When I went on a busy Friday afternoon with my daughter and a friend, we joined other masked guests kicking back in the pod spaces and reading a book about a kid’s first Pride with her two mommies and momentarily missing puppy. My daughter scratched her tiny nails against the cushion, feeling and responding to its woven texture. I wanted to linger.

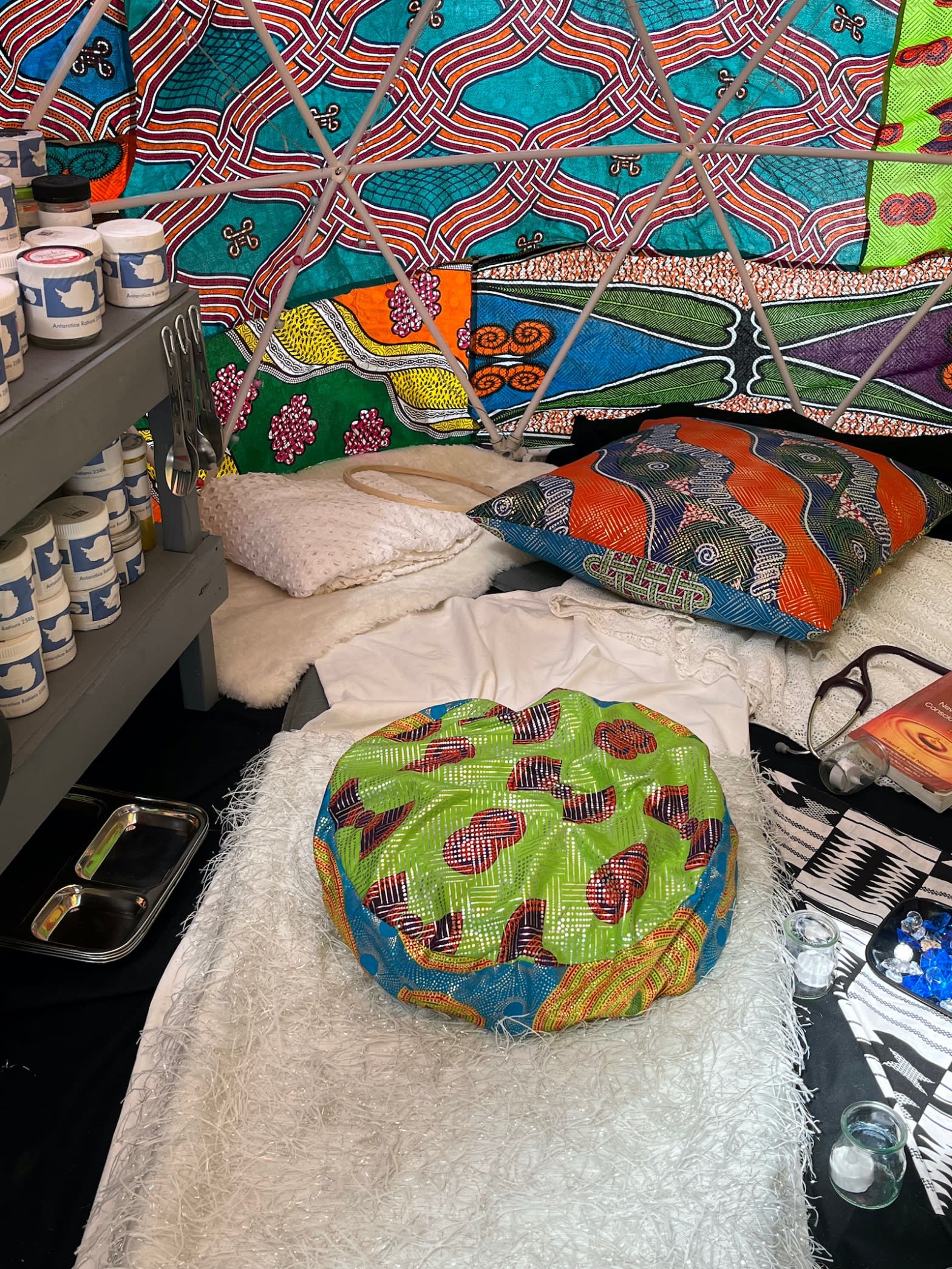

Installation view of Syrus Marcus Ware, “MBL: Freedom” (2022), African print/Dutch wax fabric, mixed-media, video, moss, lichen, mushrooms, and various materials. Background: Timothy Yanick Hunter, “True and Functional” (2022), LCD monitors, CRT monitors, mixer, dimensions variable, 5 minute 30 second loop. On view at Small Arms Inspection Building as part of the Toronto Biennial of Art.

Of the biennial’s group exhibitions, Arsenal Contemporary Art and Textile Museum of Canada succeeded as intuitive presentations considering the lineages of labor-intensive craft. The aerial installation of textile-based works by Amy Malbeuf and the Mata Aho Collective at Arsenal affords heady speculation into what it means to pare these craft processes to their bare bones. Malbeuf’s unadorned hides, a material deconstruction of Woodland Cree hide tanning, hang as un-sewn garment patterns. Meanwhile, a pair of 2014 works by the Aotearoa New Zealand-based Mata Aho Collective seamlessly merges Maori weaving with Op Art aesthetics; my daughter and I spent time sitting underneath the arch of one of the pieces, trying to grab the cut chevrons’ shadows off the floor.

ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᔪᒻᒪᕆᒃ Double Vision: Jessie Oonark, Janet Kigusiuq, and Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, the Textile Museum group show, felt warm and considerate in its sharp focus on the nivinngajuliaat, Inuit applique wall hangings created by this matrilineal Nunavut dynasty. This time capsule — which I experienced sans child because I have a life partner, mother, brother, sister-in-law, and friends who generously allow me these minute shreds of freedom to see, think, and write about art — had just the right amount of works and a fine-tuned narrative running throughout the didactics, pitching scholarly inquiry on par with oral-based histories. Ideally, Double Vision would have been envisioned as the biennial’s anchor since its historical heft provides a genuinely valuable entry point: the decolonial centering of collaboratively made artistic production passed down from elders and kin.

Outdoor view of Ange Loft with Jumblies Theatre and Arts, DISH DANCES (2022), three-channel video installation with audio, 4 minutes 24 seconds. On view at Fort York National Historic Site as part of the Toronto Biennial of Art (2022). Commissioned by the Toronto Biennial of Art in partnership with Fort York National Historic Site, Toronto History Museums.

Denyse Thomasos, “Untitled” (c. late 1980s), charcoal on paper. On view at the Small Arms Inspection Building as part of the Toronto Biennial of Art (2022) (courtesy the Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery).

Of course, even with that re-envisioning, the other, more uneven group exhibitions would still stumble. In 2019, the chaotic presentations at a former Volvo dealership downtown and the Small Arms Inspection Building, once a WWII munitions factory, in the nearby city of Mississauga, were spirited. While I can appreciate the choice this time around to pull back and embrace the openness and contemplation — or even dwell sympathetically on how the pandemic might have curtailed exhibition planning — it felt cold and clinical in execution. At the Small Arms, the material evidence of performative activations within the Eric-Paul Riege and Jatiwangi art Factory works — the regalia laying on the floor of Riege’s pseudo-childhood home, the Factory’s unplayed terracotta instruments — evoke a you-had-to-be-there pastness.

Worst, the building’s airy windows created unfortunate reflection issues that distract from an otherwise absorbing trio of framed Denyse Thomasos charcoal works and the CRT monitors in an installation by Timothy Yanick Hunter, recently long-listed for the Sobey Award. (Never mind that upon my second visit the stacked free-standing LCD monitors within Hunter’s installation were off, with an apologetic “sorry … temporarily out of service” sign positioned in front. When I reached out to the Biennial’s PR for comment, I was told that the building has power issues and occasionally goes out, impacting the media artworks onsite: “the artist and curator have been aware of the situation.”) While I let my daughter crawl over a large coffee table in an adjacent empty cafe area, I felt that what stood out most was the exhibition site’s historical “character,” and how its architectural elements — like the steel factory windows — loomed too largely.

(This also wasn’t an isolated incident: Ange Loft’s outdoor video installation at Fort York was similarly underserved by its poor presentation: a three-channel video installation, flat screens viewed from outdoors through the windows of Fort York’s museum, with a muted soundtrack. When I saw it on a cold April afternoon, I must have crisscrossed Fort York a number of times in blustery winds and ice pellets before encountering the installation. My frustration — glass reflection! Poor wayfinding! — unfortunately overwhelmed my ability to actually take on the work. This was all the more disappointing because Loft participated in both biennial editions and helped draft an Indigenous briefing on the waterfront that assisted the curators and other artists.)