Michi Meko welcomes me into his Summerhill studio on a blue and gold November afternoon. As we talk, he begins to set a new mood for the painting I am about to experience. He dims the lights, places a single stool directly in front of a wall-sized canvas and tells me to sit with the work while he goes outside for a smoke. From a stereo in the corner, Sun Ra renders into song what I am seeing: “The sky is a sea of darkness when there is no sun to light the way.”

The working title of the painting, And We Stared Unto It, seems apt. Two bands of darkness run horizontally across the surface. The lower band evokes a horizon line at night. Above it, paint splatters into starlight, and flickers of gold leaf form distant galaxies. Intersecting lines emanate from an unseen source, creating connection, geometry and distance, overwhelming distance, sublime distance. The work captures not just a sense of the awe and beauty of the cosmos at night, but also a sense of submersion, of terrifying personal obliteration in the face of both awe and beauty on such a grand scale.

Like the romantic poets before him, Meko is interested in what he describes as the moment when daylight gives over to dusk and the possibilities for transcendence within such moments. But unlike most, if not all, of the romantic poets of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Meko creates from the perspective of a black man from the American South.

For two weeks in 2017, Meko camped in the shadow of Mount Whitney in the Eastern Sierra Wilderness. Beneath a bowl of stars and an indelible Milky Way each night, he searched for what he calls “the moment when the baggage falls off.”

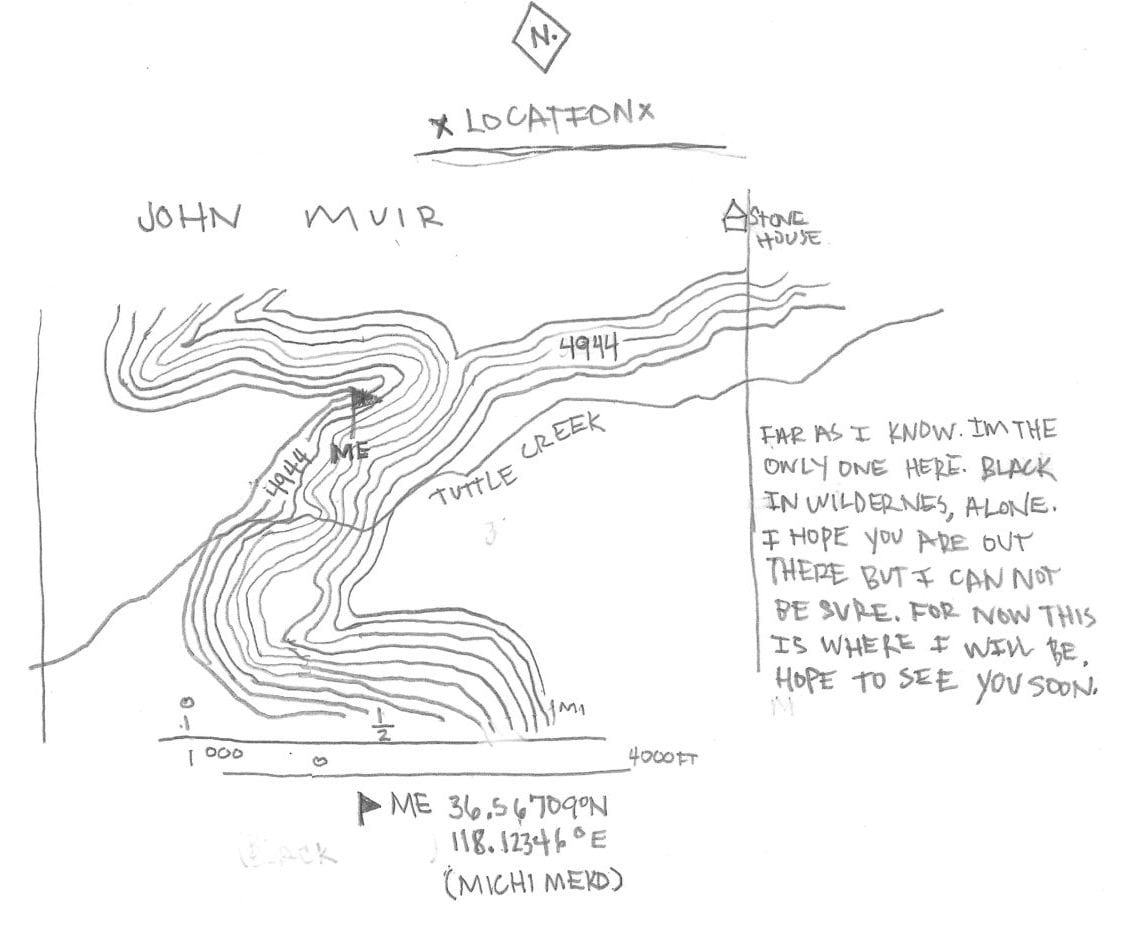

Artist Michi Meko says his notes from his time in California often reveal his sense of frustration.

He never found it. Above his campsite at 8,000 feet was the Ashram House, built in the 1930s as a place of contemplation and tolerance, but below him were the Alabama Hills, what he calls “a fucking reminder that this was Klan territory.”

The Alabama Hills were mined by 19th-century prospectors sympathetic to the Confederate cause who named their claims after the storied CSS Alabama sunk off the Normandy coast in 1862 by an armor-clad Union ship. Where, if not in the wilderness, Meko asked himself, could he find the moment to turn off that part of his brain?

That part is, of course, the weight of historical baggage of being black in America, heightened now by Trump-era politics. Meko says his ever-present sense of dread and vulnerability have lately become frustratingly inescapable.

“This is the same conversation my grandfather had, the same conversation my father had, and it’s the same conversation now that I’m still having,” he says. “Can we stop?”

Even in the beauty of the wilderness, Meko says he had difficulty getting rid of his sense of dread and vulnerability.

Meko was born in Florence, Alabama, in 1974, a decade after the Voting Rights Marches of 1965, to parents who had lived in the state through those turbulent times. Growing up, he ran through old corn and cotton fields on the antebellum Forks of Cypress plantation at night, having fun and kissing girls. Looming white columns were all that remained of the plantation, rising above fields where slaves had toiled, above a graveyard where they lay buried anonymously.

Even in the beauty of the wilderness, Meko describes his notes from his time in California as mostly revealing his sarcasm and frustration. With the Milky Way over his tent and the vast cosmos beyond, he’d hoped to soften, to transcend any politicization of the land. But, even though they faded from view in the darkness, there below him in the morning were always “those fucking Alabama Hills.”

A detail of Michi Meko’s work from his upcoming show at Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia.

Meko says his latest show, opening December 1 at Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, It Doesn’t Prepare You for Arrival, is charged with his frustrated search for peace in the natural world. The painting he invited me to sit in front of is one of only two in the exhibition. Placed with two sculptural works, the paintings are intended to create a quiet environment, a Rothko Chapel-like meditative space for contemplation.

Beneath the stars in California, Meko told himself to “have wonder,” hoping for the moment he could say, “This is me in nature, this is me existing without anyone else’s narrative.” In the sanctuary space of his new show, he hopes visitors experience something akin to what he himself is still searching for.