What sort of color is black? Is it absolute absence or absolute accumulation? Are we talking in terms of light waves or pigment? Black and its obverse, white, are exceptional colors, a fact stamped in the oxymoronic nomenclature reserved for them: achromatic colors. Yet in antiquity, the Greeks as well as the Romans had multiple words for different shades of black. Closer to us historically, a lineage of prominent Modernists and their successors have made and are making their respective careers laying bare the infinite variety within the color black. Édouard Manet’s experiments in the color stand at the origin of Postimpressionism. Kazimir Malevich, Franz Kline, Louise Nevelson, and Kerry James Marshall, among others, have all contributed substantially to art history with prolonged explorations into the possibilities of black. This is a lineage in which Atlanta-based artist Michi Meko works, as seen in the following portfolio. Through painting, sculpture, and installation, Meko has over the past decade established a practice meant to mark out the myriad ways in which black can strike the eyes.

Following the work of such painters as Kline and sculptors as Nevelson, Meko teaches us that black’s capaciousness relies on depth more so than any other color. The underlying paradox is that the de facto color for depth has the supreme capacity to obscure depth, and this is very much in play throughout Meko’s work. There are countless ways in which the black washes, marks, and lines create a variegated depth out of the surface, whether flat or sculptural. But one of Meko’s most striking techniques involves using black to provide the backdrop (or the space, if you will) for something to appear in the distance, but then using the same color to block that something—albeit partially—from one’s view. When this aesthetic effect merges with the nautical theme prominent in his work, it produces for the beholder a phenomenal state of being in which one feels always in transit. Is that horizon that runs across the middle of Meko’s I AM (2017), or two-thirds down his Wash D.C., Float the Swamp (2017), near or far? Each is the horizontal edge of a plane that obscures a plane behind it.

Michi Meko, I AM, 2019. Acrylic, white charcoal, gold leaf, and mixed media on canvas. 36 x 36 in. Image courtesy of the Georgia Review.

This is not an in transitu world in which there is one horizon always receding. Rather, it is a world of serial deferral, of Zeno’s Paradox. Behind this horizon is another, behind that yet one more. As John Milton says of hell, there is “in the lowest deep a lower deep.” This is not an existence defined by a single journey, a Bildungsroman. It is an odyssey, a life comprised of endless journeys from this place to that. The horizon is not even the promise of the absolute fulfillment of a life. We expect to reach it, but it is only a middle distance for this life ever on the move.

That Michi Meko is a Black American makes this work conversant with, if not actively participating in, what is being collectively worked out and theorized now as black fugitivity. Black abolitionist writers of the nineteenth century knew very well that a legitimate black subjectivity requires movement like no other type of body does. But in recent years there has been a collective, loosely coordinated effort to demonstrate that the black body’s exceptional artistic and critical ability lies precisely in the fact that it is always in flight. As Fred Moten, a man of letters at the forefront of the current movement, states of “blackness-as-fugitivity,” “the Negro must be still, but must still be moving.”

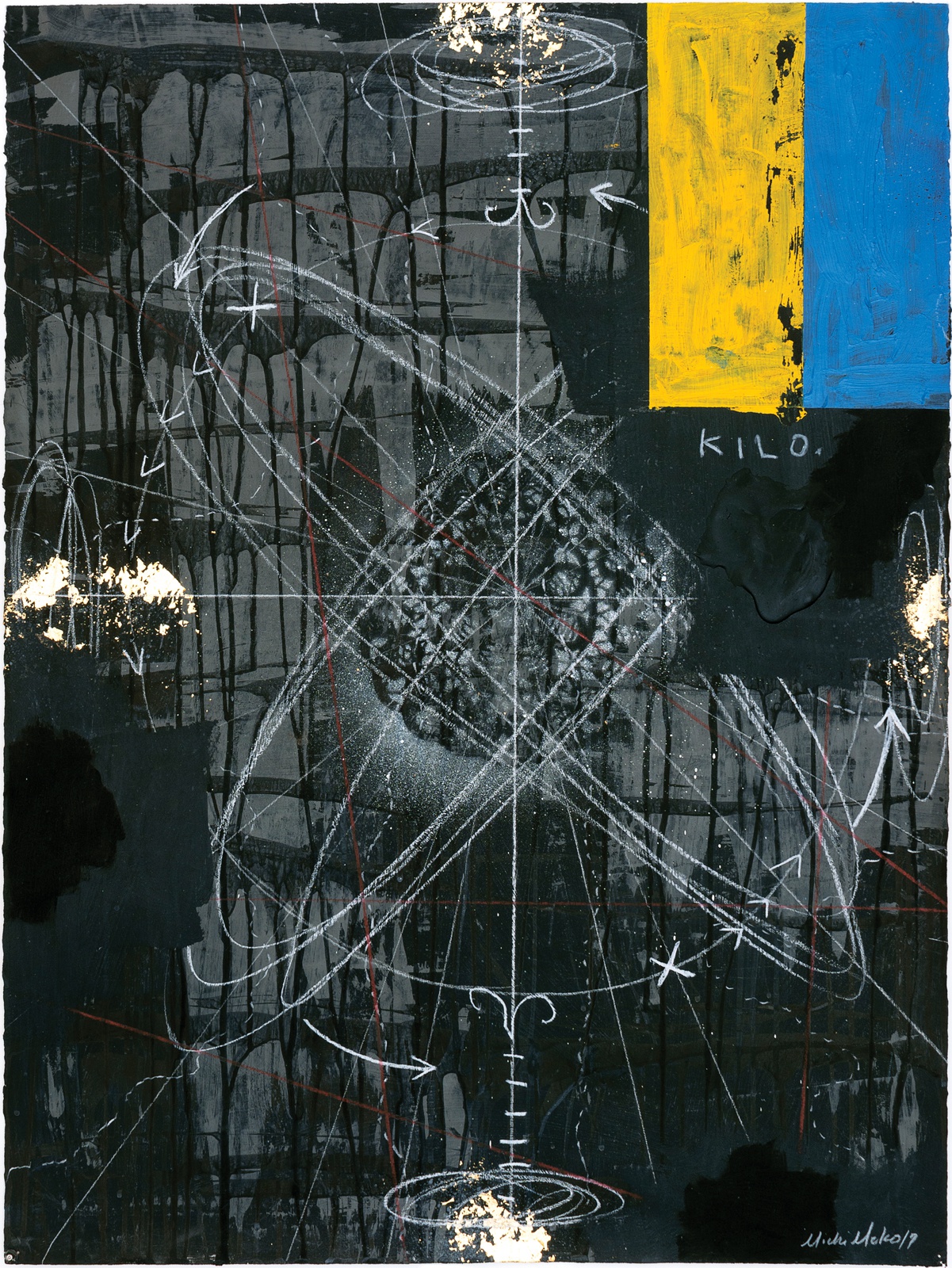

Michi Meko, KILO, 2019. Acrylic, white charcoal, gold leaf, and mixed media on paper. 30 x 22 in. Image courtesy of the Georgia Review.

The paradox here, which we can see in Meko’s art, is that this fugitivity encompasses stillness too. Fugitivity here is a state of being, not merely a physical state. Once you’ve fled, you’re always fleeing, whether you like it or not, even if you’ve made it past the Mason-Dixon line, as the Fugitive Slave Act decreed. So stillness is also implicated. To hide, wait out, and still one’s breath are all survival tactics in a life always on the move. So the trompe l’oeil effect of near/far present in many of Meko’s works does more than just deceive the eye. Rather, it dislodges the viewer from any sense of secure grounding, as Paul Cézanne’s celebrated still-lifes and landscapes do. The beholder is fixed in place, more or less, but floating this way and that, as so many things do in the ocean, anchored or not. One can be in the state of fugitivity when arrested before a piece of art.

Michi Meko uses the ostensibly static medium of the art object to induce a sort of fugitive state in its beholder. Existential seasickness—“anxiety,” he called it when we spoke—or a sort of black nausea, a vertiginous state particular to living life in America within a black male body. We can tie aesthetic experiments in black securely to meditations on black life, because in Meko’s oeuvre there are enough textual and visual references that signal a debt to a black world (might I add, a particularly Southern black world) that one can—must—look at his art with the understanding that a black sensibility is prominently and explicitly at work. That is, although the art is essentially abstract, it assembles its materials and forms from the world of black life and culture immediately surrounding him.

Michi Meko, SHE (detail), 2018. Mixed media and found objects. Image courtesy of the Georgia Review.

The work presented here gives us only a beginning sense of Meko’s commitment to representing, abstractly, black culture locally. Family history, regional culture, and the cultivation of personal life practices are powerful means by which to prove infinite variegation within something designated as a single culture. We can see that the wishbone in the center of Wishes: A Promise to Send Us Into Ourselves. Free to Travel, Adrift from our Pagan Land (2019) comes from the fowl so central to the caricatures, but also real lives, of black communities. The oyster shell and blackened buoys localize the provenance for this piece to the southern gulf that runs along the edges of Meko’s birth state, Alabama, and his current home state, Georgia, which draws the chicken bone away from the world of caricature to an existence in the material world.

In my interview with Meko, which can be found on The Georgia Review’s website, you can learn more about this life’s work, particularly in terms of his attachment to nature. The natural world has become an important topic for him, through which he works against what he calls the “Americanisms” that delimit the possibilities of black life. An avid fisherman and camper, Meko sees firsthand that the triumphal American myths and arguments that have resulted in the preservation of great swaths of nature rely heavily on the race line that defines white from black, wealth from slavery, leisure from work. Ultimately, the wilderness that Meko seeks is not relegated to the forests, mountains, and lakes. “If you go out to the city,” Meko says, “that becomes your wilderness”; he adds that “with wilderness there is room for discovery, to see oneself in this environment, to now exist and survive in that environment.”