A Long Overdue Recognition: James Little Finally Gets His Turn in the Spotlight at this Year’s Whitney Biennial

Some artists find global acclaim fresh out of art school. Others toil a lifetime in obscurity, only to be discovered—if they’re lucky—long after their death. So there’s something particularly stirring about artists who finally receive the recognition they deserve after pursuing their work for decades upon decades, to the exclusion of all else. Such is the case with 70-year-old painter James Little, a participant in this year’s Whitney Biennial, who will also be honored in a solo exhibition at Chicago’s Kavi Gupta gallery this fall.

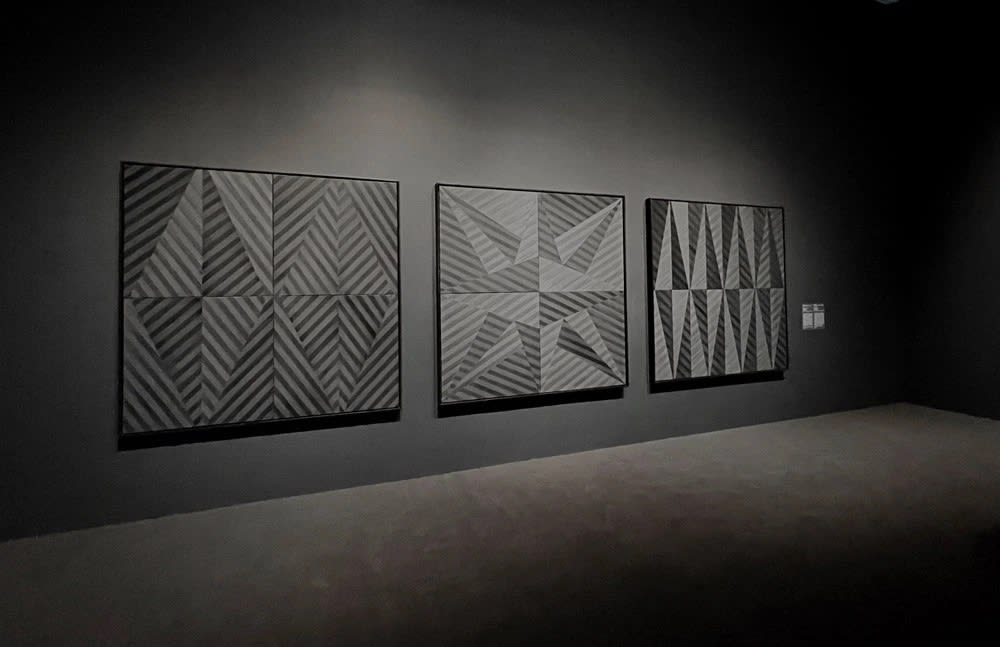

Though always well regarded within his immediate circle, Little has flown under the art world’s radar for more than half a century—until now, thanks to his inclusion in the 2022 Biennial, where more than half a floor is dedicated to his series of “Black” geometric compositions. The seven grisaille canvases that fill the space are a revelation, establishing once and for all Little’s importance as an American master of Abstraction. The show is the fulfilment of a long-held dream, he says: “When I got out of graduate school and came to New York, being recognized in the Whitney Biennial was the one thing I wanted more than anything else—anything.”

Little’s late-career flowering was the result of both choice and circumstance. Instead of attempting to appeal to the fleeting tastes of the art market, he always focused first on the principles of his medium, engaging in a rigorous study of color theory, pictorial design, and painting technique. At the same time, like most African American artists, he was consistently undervalued by white dealers, collectors, and curators. This was especially true during the 1970s, a period dominated by Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Performance Art. By then, Little’s formalist approach—and, indeed, painting itself—was out of fashion; but Little didn’t care, describing himself as “a guy who just stuck to his guns… It sounds stubborn as hell, but that’s me.”

Little’s determination was, to a large degree, shaped by his background. He was raised in Memphis, Tennessee, during the 1960s; and though the Civil Rights movement had begun to dismantle the strictures of the Jim Crow South, the city remained highly segregated, forcing him to stay mindful of where he could and couldn’t go, lest he attract the attention of the Ku Klux Klan or other racists bent on violence. His parents both worked, his mother as a cook, his father as a construction worker. And while Little says the family’s financial situation wasn’t “dire,” they did live paycheck to paycheck, an experience that instilled in him frugal habits—such as grinding his own paints and mixing his own additives and binders—that continue to this day. “I had to learn how to invent things and be creative,” he says. “I buy raw materials and create my own stuff instead of getting it off the shelf. Rather than pay $50 for a quart of varnish, I can make it for $10. All these things play into the whole idea of not having something.”

Yet, despite their difficult circumstances, Little’s parents supported his artistic ambitions. He notes how unusual this was at the time: “If you were from Memphis, you became a musician, an athlete, or a minister,” he says. “That was it. There was nothing else.” As a very young child, he was inspired to draw by watching his older brother work on art assignments he brought home from school. When he was 8, his mother gave him a paint-by-numbers kit for Christmas; after finishing it, he wondered what to do with the leftover paint, and his father offered a solution by giving him pieces of shirt cardboard from the cleaners. Little used them to render copies of a painting by Thomas Eakins he found in an encyclopedia.

Yet, despite their difficult circumstances, Little’s parents supported his artistic ambitions. He notes how unusual this was at the time: “If you were from Memphis, you became a musician, an athlete, or a minister,” he says. “That was it. There was nothing else.” As a very young child, he was inspired to draw by watching his older brother work on art assignments he brought home from school. When he was 8, his mother gave him a paint-by-numbers kit for Christmas; after finishing it, he wondered what to do with the leftover paint, and his father offered a solution by giving him pieces of shirt cardboard from the cleaners. Little used them to render copies of a painting by Thomas Eakins he found in an encyclopedia.

Another formative experience in Little’s art education occurred at Syracuse University, where he went to graduate school in the mid-1970s. There he attended seminars taught by New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer as well as writer and critic Clement Greenberg, an SU graduate who played an essential role in promoting the ascendency of American art after World War II, when New York displaced Paris as the world’s art capital. Greenberg championed Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Hans Hofmann, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still, insisting they were the true inheritors of the Modernist avant-garde because they pursued pure abstraction through “medium specificity”—that is, applying paint for its own sake, without reference to subject matter or spatial depth.

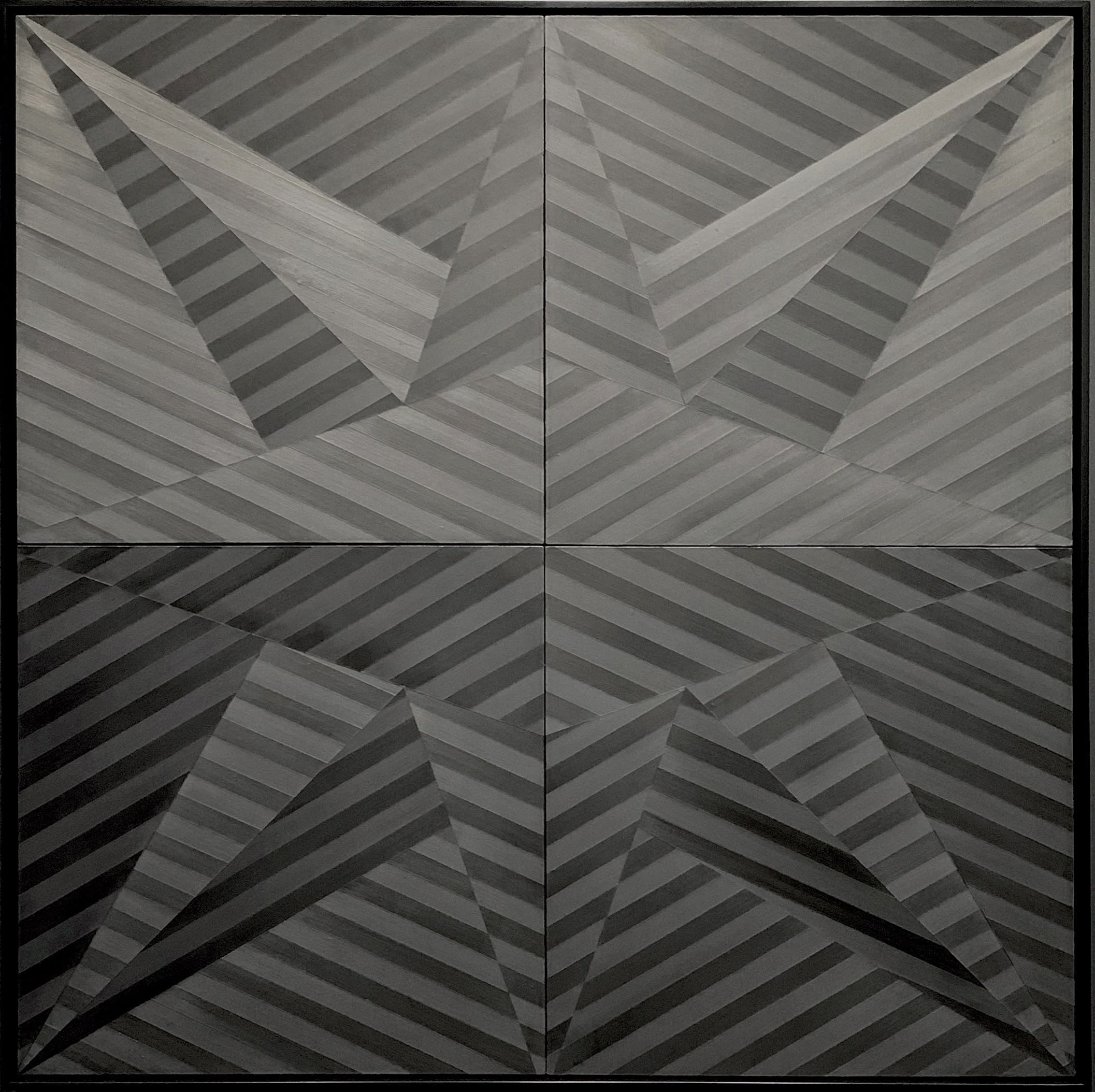

This emphasis on “flatness,” as it was more generally referred to, dates back to Maurice Denis—a late-19th-century artist associated with the Symbolists and the Nabi group—who postulated that above all else, a painting was “a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” Greenberg; the Abstract Expressionists; and, later, Color-Field painters such as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland followed Denis’s notion to its logical conclusion. Their example was not lost on Little: “I want to create a flat, frontal, modernist space and eliminate as much illusion as I possibly can,” he says of his technique. “But I also want an animated space that’s engaging.”

This emphasis on “flatness,” as it was more generally referred to, dates back to Maurice Denis—a late-19th-century artist associated with the Symbolists and the Nabi group—who postulated that above all else, a painting was “a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” Greenberg; the Abstract Expressionists; and, later, Color-Field painters such as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland followed Denis’s notion to its logical conclusion. Their example was not lost on Little: “I want to create a flat, frontal, modernist space and eliminate as much illusion as I possibly can,” he says of his technique. “But I also want an animated space that’s engaging.”

While Little has used both raw pigment on paper and conventional oils on canvas, the material he’s most frequently associated with is one that dates back millennia: encaustic. Believed to have been invented in Ancient Greece, encaustic—a mixture of varnish, pigment, and wax heated to a liquid state—is difficult to use. As he does with most everything else, Little formulates his own encaustic, then flattens them out in smooth layers arrayed in hard-edged patterns like chevrons, angled striations, and triangles. And though he acknowledges his appreciation for the medium’s “robust and central qualities,” Little says he also wants to “expand it beyond the conventional notion of encaustic, so when you look at my paintings, you don’t really know what medium they’re made with.”

Regarding art world expectations that his work address issues of race, Little has resisted being pigeonholed, remaining true to his commitment to abstraction. While perfectly content for people to interpret his “Black” paintings through the prism of race—“Because I’m Black, people try to see that in the work, and part of it is true”—he also rejects an outright pursuit of the issue. “I don’t buy it,” he says. “But if you want to go out there and paint these things about race and that kind of thing, I mean, be my guest.”

Regarding art world expectations that his work address issues of race, Little has resisted being pigeonholed, remaining true to his commitment to abstraction. While perfectly content for people to interpret his “Black” paintings through the prism of race—“Because I’m Black, people try to see that in the work, and part of it is true”—he also rejects an outright pursuit of the issue. “I don’t buy it,” he says. “But if you want to go out there and paint these things about race and that kind of thing, I mean, be my guest.”

Still, he adds, dealing with racism in the abstract pales in comparison to what he experienced first-hand, growing up in the tumult of the segregated South. He also cites the transient nature of making work topical, posing a hypothetical: “What if things change tomorrow, and we don’t have racism anymore? What do you paint then? That’s why I paint pictures for everybody. Race doesn’t have a space in my art.”

Although the Biennial showcase will certainly expose Little’s work to a much wider audience, it hasn’t gone completely unnoticed over the years. In 2009, the artist received the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award in painting; and in 1980, he was included in the group show “Afro-American Abstraction” at MoMA P.S.1, along with such luminaries as Mel Edwards, Ed Clark, Sam Gilliam, Richard Hunt, Al Loving, Martin Puryear, Jack Whitten, and William T. Williams.

Yet only now is Little receiving his due. His perseverance over five decades has been remarkable, especially considering the number of artists who, in the course of history, have simply given up in the face of such seeming indifference. But Little’s passion for painting and art history, as well as his belief in the universality of art, always kept him going. He didn’t—and, perhaps, couldn’t—quit.

“Art is like religion to me,” he says. “It has to have feeling and emotive content, and it has to be transcendent. If it lacks that, then it’s just clinical. It’s a clinical exercise.”

James Little in the 2022 Whitney Biennial, Kavi Gupta.

Forthcoming: James Little, Kavi Gupta | Elizabeth Street FL 1, Nov. 12 – Dec 20, 2022

Individual works in order of progression:

1. James Little, Big Shot, 2021. Oil and wax on linen, 72 x 72 in

2. James Little, Exceptional Blacks, 2021. Oil and wax on linen. 72 x 72 in.

3. James Little Stars and Stripes, 2021. Oil and wax on linen. 72 x 72 in.