Back in the day, I used to play a game while riding the NYC subway that I called “guess the artist.” This game, intended to eat up time, involved scanning the passengers in my subway car to decide which one of them was an artist. There was, of course, no shortage of style to be found on the NYC subway, and so I could always identify someone with sufficiently inventive hair or earrings or tattoos to look the part.

Arghavan Khosravi does not look the part. When we meet over video call, her long dark hair is pulled back in a plain ponytail and her pretty face is unadorned. She wears a pale pink turtleneck. Her voice matches her style: soft and tasteful. Then she makes a hand gesture, and I see something on her arm where the sleeve is rolled up. It’s black paint streaks smeared all along her skin, the type of a mark that could only belong to an artist who has already been at work long before our 9am call.

Khosravi is Iranian—she was born in 1984, five years after the Islamic Revolution that propelled Iran into religious fundamentalist rule—but she has lived and worked in the United States since attending the Rhode Island School of Design for an MFA in Fine Art in 2018. These days she lives in Stamford, Connecticut—close enough to New York City to attend shows, but far enough away to avoid distraction. In Stamford, Khosravi transformed her garage into a woodworking studio and her loft into a painting studio. She paints, she tells me, ten hours each day. “Eleven,” she says, “is a good day.”

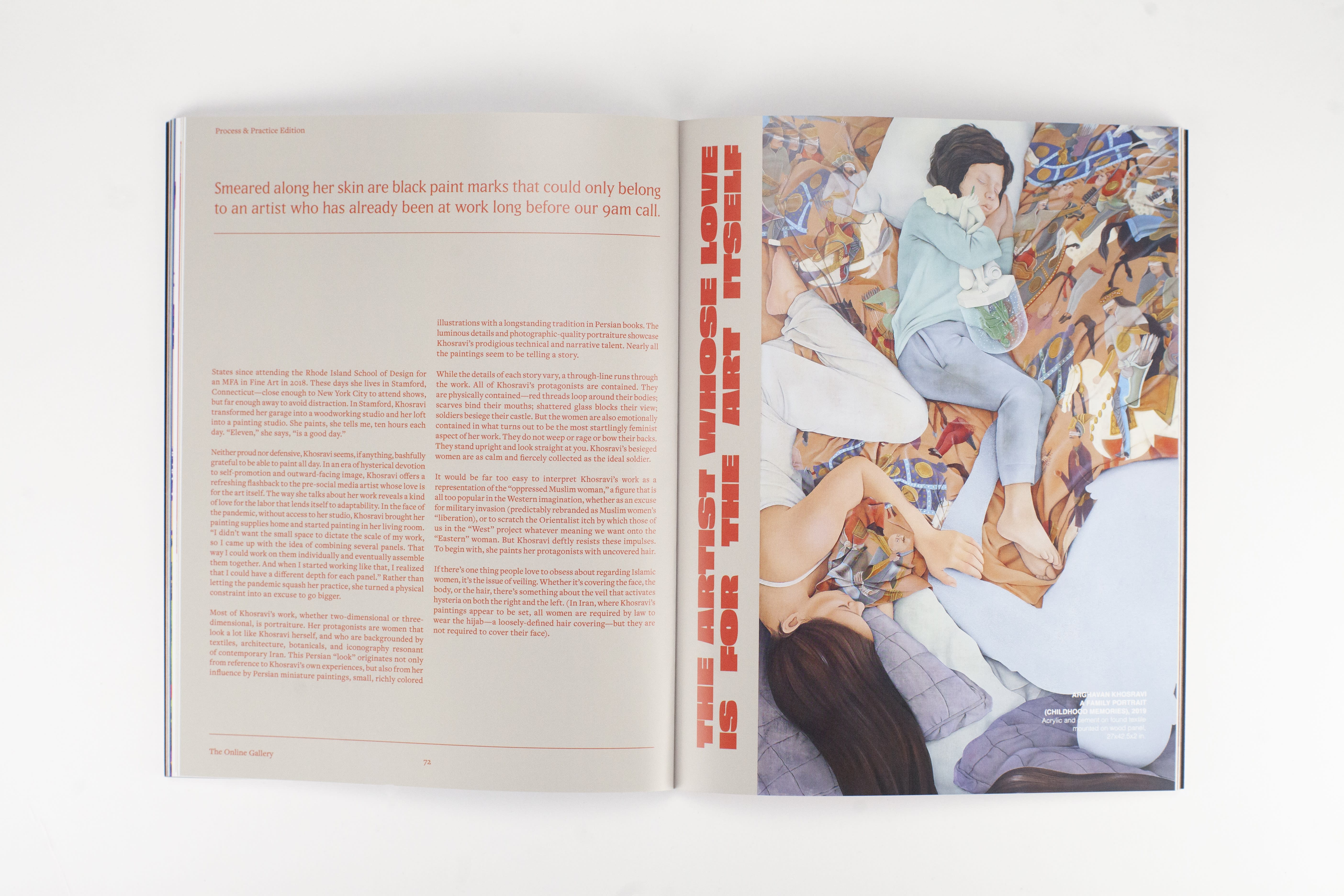

Neither proud nor defensive, Khosravi seems, if anything, bashfully grateful to be able to paint all day. In an era of hysterical devotion to self-promotion and outward-facing image, Khosravi offers a refreshing flashback to the pre-social media artist whose love is for the art itself. The way she talks about her work reveals a kind of love for the labor that lends itself to adaptability. In the face of the pandemic, without access to her studio, Khosravi brought her painting supplies home and started painting in her living room. “I didn’t want the small space to dictate the scale of my work, so I came up with the idea of combining several panels. That way I could work on them individually and eventually assemble them together. And when I started working like that, I realized that I could have a different depth for each panel.” Rather than letting the pandemic squash her practice, she turned a physical constraint into an excuse to go bigger.

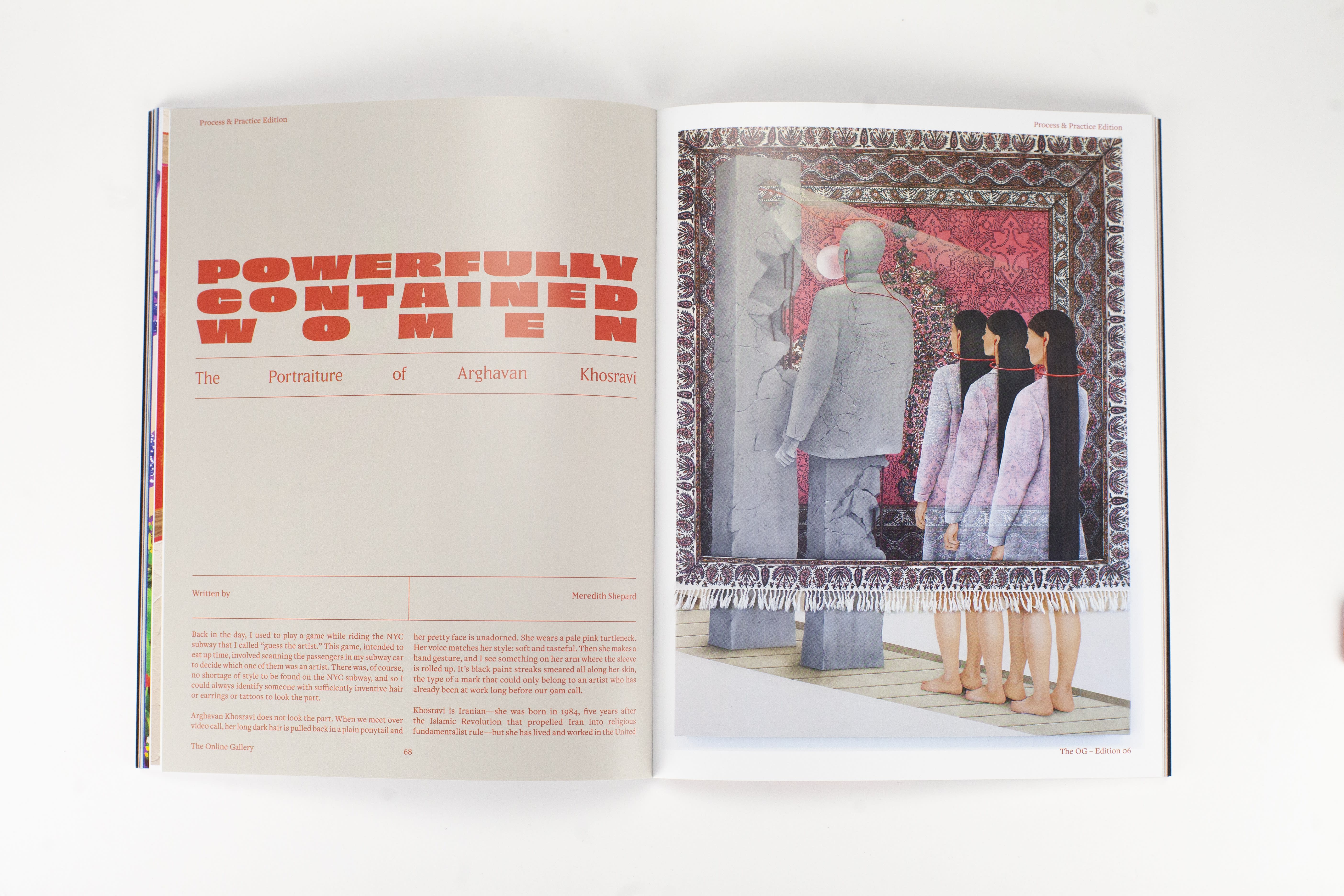

Most of Khosravi’s work, whether two-dimensional or three-dimensional, is portraiture. Her protagonists are women that look a lot like Khosravi herself, and who are backgrounded by textiles, architecture, botanicals, and iconography resonant of contemporary Iran. This Persian “look” originates not only from reference to Khosravi’s own experiences, but also from her influence by Persian miniature paintings, small, richly colored illustrations with a longstanding tradition in Persian books. The luminous details and photographic-quality portraiture showcase Khosravi’s prodigious technical and narrative talent. Nearly all the paintings seem to be telling a story.

While the details of each story vary, a through-line runs through the work. All of Khosravi’s protagonists are contained. They are physically contained—red threads loop around their bodies; scarves bind their mouths; shattered glass blocks their view; soldiers besiege their castle. But the women are also emotionally contained in what turns out to be the most startlingly feminist aspect of her work. They do not weep or rage or bow their backs. They stand upright and look straight at you. Khosravi’s besieged women are as calm and fiercely collected as the ideal soldier.

It would be far too easy to interpret Khosravi’s work as a representation of the “oppressed Muslim woman,” a figure that is all too popular in the Western imagination, whether as an excuse for military invasion (predictably rebranded as Muslim women’s “liberation), or to scratch the Orientalist itch by which those of us in the “West” project whatever meaning we want onto the “Eastern” woman. But Khosravi deftly resists these impulses. To begin with, she paints her protagonists with uncovered hair.

If there’s one thing people love to obsess about regarding Islamic women, it’s the issue of veiling. Whether it’s covering the face, the body, or the hair, there’s something about the veil that activates hysteria on both the right and the left. (In Iran, where Khosravi’s paintings appear to be set, all women are required by law to wear the hijab—a loosely-defined hair covering—but they are not required to cover their face).

I ask Khosravi if, by painting women without the hijab, she is rejecting Western assumptions that Iranian women cover their hair. “I don’t think about that expectation that much,” she answers. “Because, again, that can also be limiting, right?” What’s more interesting to Khosravi is representing contradiction, the experience of living a double life. She explains that, “in Iran, we are forced to wear a hijab in public but not in private. I grew up with parents who drank alcohol and listened to rock music, but I couldn’t speak about these things at school. Everyday life is a contradiction.”

Contradiction then, is a better paradigm than oppression or rebellion to make sense of Khosravi’s portraits’. When I inquire if depicting women without hijabs means that they are set in private spaces, she explains that that is not necessarily the case. In other words, when Khosravi’s protagonists wear their hair uncovered, they do so in a way that does not map neatly onto politics. That’s because Khosravi is painting outside the sort of logic that politicizes women’s hair. Therefore, she does not have to make sense within its framework. Her work could (thankfully) never be considered “political” in that dumbly didactic way that sets up a one-to-one equivalence between art and its “message.”

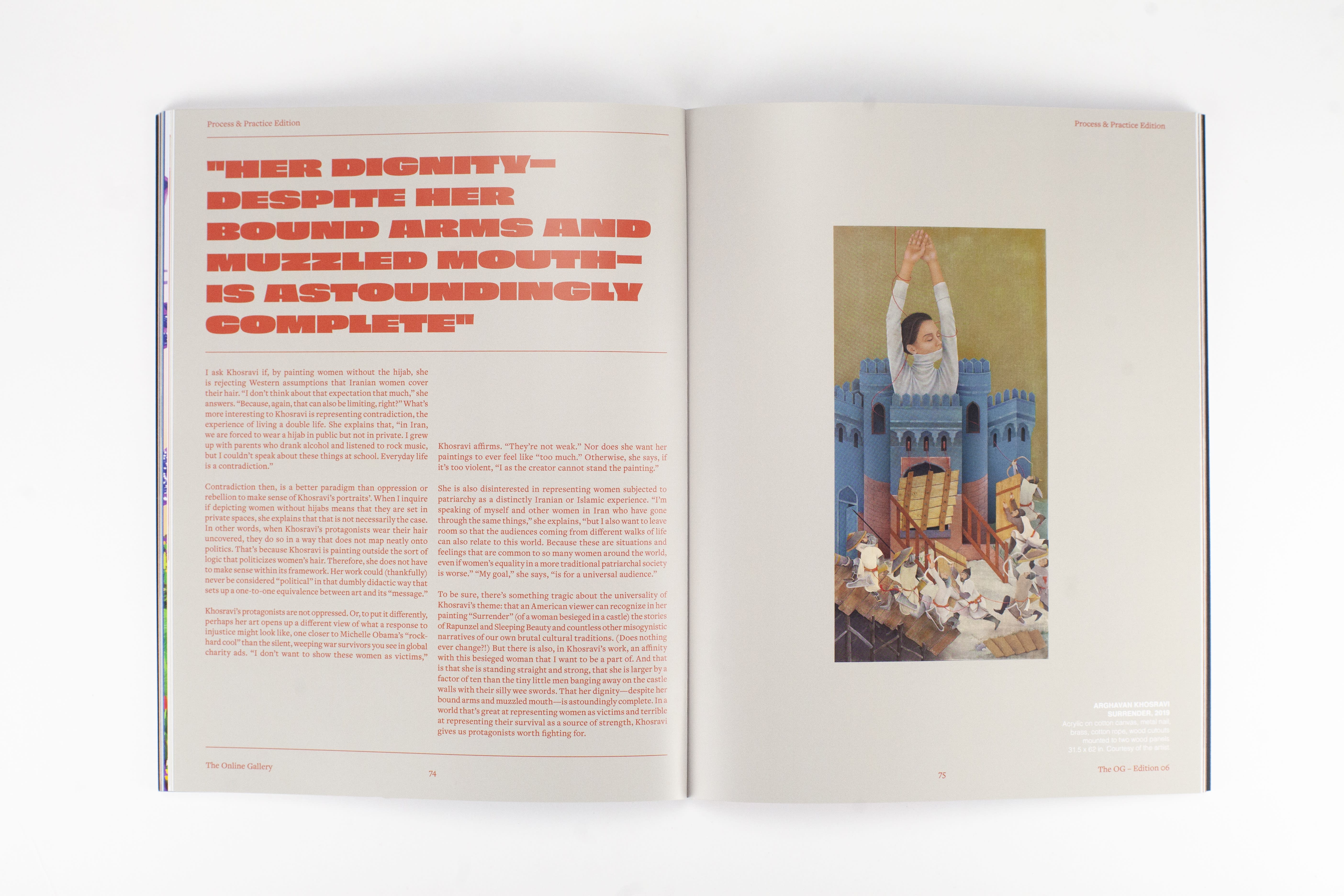

Khosravi’s protagonists are not oppressed. Or, to put it differently, perhaps her art opens up a different view of what a response to injustice might look like, one closer to Michelle Obama’s “rock-hard cool” than the silent, weeping war survivors you see in global charity ads. “I don’t want to show these women as victims,” Khosravi affirms. “They’re not weak.” Nor does she want her paintings to ever feel like “too much.” Otherwise, she says, if it’s too violent, “I as the creator cannot stand the painting.”

She is also disinterested in representing women subjected to patriarchy as a distinctly Iranian or Islamic experience. “I’m speaking of myself and other women in Iran who have gone through the same things,” she explains, “but I also want to leave room so that the audiences coming from different walks of life can also relate to this world. Because these are situations and feelings that are common to so many women around the world, even if women’s equality in a more traditional patriarchal society is worse.” “My goal,” she says, “is for a universal audience.”

To be sure, there’s something tragic about the universality of Khosravi’s theme: that an American viewer can recognize in her painting “Surrender” (of a woman besieged in a castle) the stories of Rapunzel and Sleeping Beauty and countless other misogynistic narratives of our own brutal cultural traditions. (Does nothing ever change?!) But there is also, in Khosravi’s work, an affinity with this besieged woman that I want to be a part of. And that is that she is standing straight and strong, that she is larger by a factor of ten than the tiny little men banging away on the castle walls with their silly wee swords. That her dignity—despite her bound arms and muzzled mouth—is astoundingly complete. In a world that’s great at representing women as victims and terrible at representing their survival as a source of strength, Khosravi gives us protagonists worth fighting for.