For those who revere the ancient visual art of painting as the finest of the fine arts, there is not a lot to see at the current edition of the biennial survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Those expecting to see mainly painting and sculpture at a broad show of contemporary art these days are in for disappointment. Those wanting to enter a state of confusion about what constitutes art, or to be scolded politically or lectured academically, will find a kind of entertainment at this Biennial.

Since early in the 20th century, when Picasso and Braque stuck pieces of newspaper and wallpaper in their paintings to liven up the perceptions of space in them, a branch of artists has been fascinated with the question of just what can constitute painting. Particularly since the 1960s, we have seen uncountable variations on the shape of the canvas, the placement of the image in real space, and the materials used.

Yet a flat, rectangular canvas is a shaped canvas — and it’s one that, with paint on it, holds a clear, specified image. There is a reason why most painters since the Renaissance have preferred it.

The practicality of being able to move a painting from place to place has a role in this, but the longevity of this traditional format of painting is because it’s a place that the greatest artists for hundreds of years have, for aesthetic reasons, found to be the best for painting, for deepest communication by marks on a surface.

Another modern diversion from the rigors of painting has come to be known as conceptual art. This also began in the early 20th century, when Marcel Duchamp decided that painting, what he mocked as “retinal” art, was too much trouble. He preferred to concentrate on some of the ideas and questions one might find in it and isolate from it.

This too resulted in a branch of art, still with us, that eschews painting in favor of philosophizing about it. Its practitioners fail to notice that these ideas and questions always have resided in painting and are much more interesting when found within the richness of real painting.

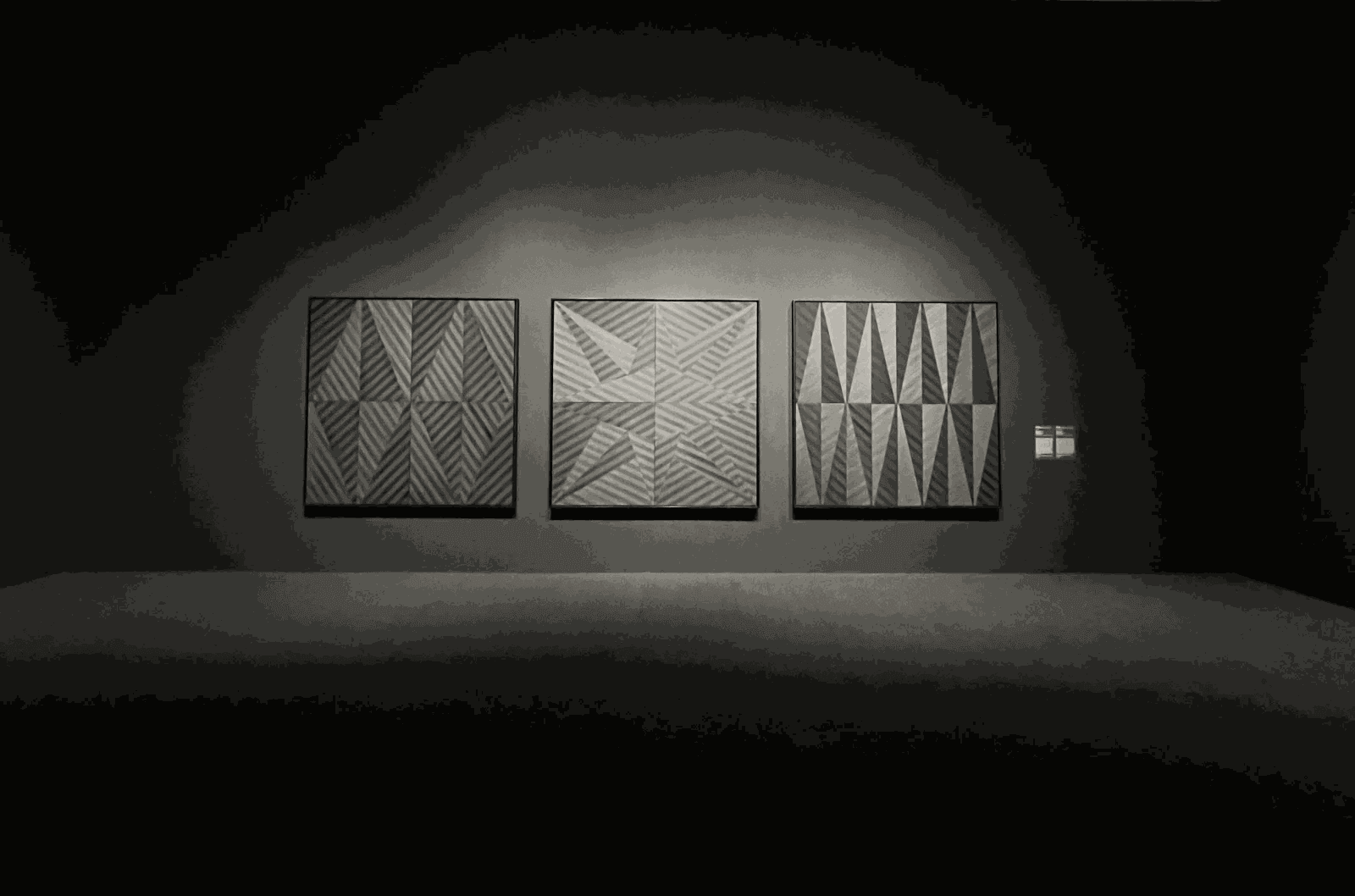

Installation view of three works, from 2021 by James Little: from left, Stars and Stripes, Big Shot, and Exceptional Blacks.

In the Whitney show of 63 artists, about 10 are working in this old-fashioned sense of

painting. The one who addresses the art of painting in the purest and most complete way possible is James Little. In his thoroughgoing engagement with the nature of art, the integrity of his work is complete — it embraces what a painting is and what a painter does.

In the recent decades of his long career, Mr. Little’s paintings have been made up of clearly defined geometric shapes and strips of highly specific color relations — indeed, so specific he has been mixing the paints himself from powdered pigments and mediums. Color is the main transporting mechanism of idea and feeling in his art; pattern is a major theme as well.

Unexpectedly, in this Biennial the artist is represented by paintings that do not — at first consideration — have much color in them. In a way this is a shame, because this artist's use of color and pattern deserves to be featured in a major museum show in New York City, where he has been resident since 1976.

Yet in the Whitney show his large, magnificent, and quiet triptych of three paintings, “Stars and Stripes,” “Exceptional Blacks,” and “Big Shot,” is a major statement about what counts in painting, and by implication in all art. You can think about this if you are lucky enough to take it all in without interruption from passersby (contemplation is not something you are encouraged to do by the curation of this show).

These three serious objects stand with such dignity and the simultaneity of the large canvases makes you want to look at the entire triptych but it's hard to pin it down, to know how to look at it. This is not an accident.

Its many repeated shapes in insistent but gentle patterns are filled by only a few shades of gray. Mr. Little is inviting you in, to swim around in his arrangement of forms as you please, and to feel what this state of existence means. Turning the three paintings into a triptych has made this experience even more profound.

Are grays colors? Gray is made by mixing black and white, though added color can tint it. In paint and in light, black is the absence of light and of color. White is the mix of all colors. Yet black is as insistent as white.

So, this painting is a pattern of no color and all color, but also of black and white. Of insistence and of calm. Of intensity and of chilling out. All the more, it is a stunning work of art.

Mr. Little does not do authoritarian, political paintings. His subjects, and the viewer's experience of his paintings, are purely visual — but you can only fully understand this if you see that the abstract visual can carry emotion and meaning. And why would it be otherwise?

“[Clement] Greenberg gave me my theory. He teaches you to take a stand against decadence in art. You have to set high standards, and reach them,” the artist has said.

In the way Mr. Little sticks to principles and to the essences of the art of painting, his work is the most powerful in the Biennial.

As thrillingly lucid and authoritative as his art, Mr. Little is succinct about his inspiration: “What I ascribe to in my art are modernist tenets.... Modernism to me is like democracy.... Coming from my background, which was a very segregated upbringing in Tennessee, I felt that abstraction reflected the best expression of self-determination and free will.... It was liberating. I don’t find freedom in any other form. It’s up to you. You have to determine the outcome for yourself.”