The Oral History Project is dedicated to collecting, developing, and preserving the stories of distinguished visual artists of the African Diaspora. The Oral History Project has organized interviews including: Wangechi Mutu by Deborah Willis, Kara Walker & Larry Walker, Edward Clark by Jack Whitten, Adger Cowans by Carrie Mae Weems, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe by Kalia Brooks, Melvin Edwards by Michael Brenson, Terry Adkins by Calvin Reid, Stanley Whitney by Alteronce Gumby, Gerald Jackson by Stanley Whitney, Eldzier Cortor by Terry Carbone, Peter Bradley by Steve Cannon, Quincy Troupe & Cannon Hersey, James Little by LeRonn P. Brooks, William T. Williams by Mona Hadler, Maren Hassinger by Lowery Stokes Sims, Linda Goode Bryant by Rujeko Hockley, Janet Olivia Henry & Sana Musasama, Willie Cole by Nancy Princenthal, Dindga McCannon by Phillip Glahn, and Odili Donald Odita by Ugochukwu C. Smooth Nzewi. Donate now to support our future oral histories.

James Little has worked nearly half a century at mastering the craft of painting. While our conversation here delves into his painterly “alchemy”—he makes all his own paints and mixes beeswax and varnish into it—it also documents a life in painting. Born into a family of artisans with high expectations in a segregated Memphis, the artist learned the value of hard work, creativity, and persistence. His experimentation with the transformative properties of his materials reflects these emphases, and his search for excellence mirrors the work ethic of the community that raised him. This is to say that memory has its textures and its colors—their own connotative ends; Little’s paintings demonstrate a quest for the perfection of craft, but do not covet certainty despite the precision with which they are ordered. His paintings are guided by intuitive responses to form, color, and feeling. This approach is not overly calculated, though its complexity may suggest so. His expression is personal—visceral exchanges between memory and its hues, between emotion and the logistics of its use, between logic’s place in the fog of the human heart, and the ways that rationale can be envisioned as painterly “surface.” Here, to speak solely of order is to imply, in some way, process, but this implication does not necessarily suggest the course of a method as the ends of his labor’s purpose. Little’s “purpose” cannot be narrowly defined by his methods nor is it all a simple matter of procedure.The imagination has its own speculative ends and its interchanges with the world are, in Little’s paintings, as vibrant and curiously bedecked as any prism thread with light. What follows is a conversation about artistic vision, practice, and the importance of perseverance. It is a document concerned with valuing painting as of form of experiential evidence, and the imagination as a vivid context for human worth, history’s propositions, and a life’s purpose.

— LeRonn P. Brooks

James Little, El-Shabazz (B), 1985, oil and wax on canvas, 24.8 x 24.8 in.

LeRonn P. Brooks: So James, I’d like to start by speaking about your childhood in Memphis, before you became an artist. What was the South like when you were a child?

James Little: Memphis was a very segregated city when I was growing up in the ’60s. It’s just north of the Mississippi border. My family is from Mississippi. My father, Rogers Little, his family migrated from Georgia. There were a lot of Irish, Native American, and black people in his family. My mother’s family came out of the Carolinas and the West Indies. Somehow, she ended up in Mississippi. That’s where my mother was born along with a lot of her siblings. When I was growing up we were very poor. And my father worked very hard, so did my mother. But we weren’t as poor as the majority of the people around us. You know, we actually lived pretty well. My mother was a great cook. Both my parents grew up growing their own food. They knew how to survive. They were very efficient, hard-working, and God-fearing people. But you know, that was kind of the way it was.

It was very segregated in those times. We used to live in a neighborhood where there was a white-only elementary school. It wasn’t even a block away from where we lived. It was just down the street, a white school that me and my six siblings couldn’t attend. We had to walk way somewhere else to go to school. And the white kids had to walk a ways away to go to the school across from our house. So, it was that kind of segregation. But we were sheltered from it by our parents because there was so much crime being committed by racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan and that kind of thing. We just knew that there were certain places we didn’t go at night. There was a certain time you had to be home. A lot of things that are going on now with the police used to go on all the time in Memphis. It happened on a regular basis in my community, when I was growing up. So, the only thing my folks wanted us to do was to survive.

And the question you asked, What was it like when I wasn’t an artist? For me, most of what I remember is being an artist. I started painting when I was about eight years old after my mother bought me a Paint by Numbers kit for Christmas. But I had shown her that I had a penchant for drawing early on.

LPB: Did you know any other artists in the area?

JL: No. The first time I saw anybody making art was my older brother, Monroe. He’s almost five years older than me. He could draw pretty well for his age. He used to bring home his assignments from school. I saw his drawings and I liked them, so I started drawing too. I copied comic strips and that kind of thing. I immediately fell in love with it. I tried other things though, like sports and what have you. But art was the thing that I enjoyed the most and I stuck to it. After my mother bought me the Paint by Numbers kit, I quickly finished the entire set. I just used the remainder of the paint to copy old masters.

LPBShe knew you had a proclivity for the arts.

JL: Yeah, she knew. She encouraged me. Most parents would prefer their kids to pursue practical professions. When I was growing up you would get a job in construction or you’d get a job that’s going to pay you some money. You know, you’re getting a paycheck every week. So, parents wouldn’t usually encourage their kids to go into a profession that wasn’t practical. But nonetheless I did it, and I did it during a dark period of extreme segregation.

LPBCan you say more about that? What was segregation like at the time?

JL: It was horrible. The blacks had to go to the rear of the building to see a doctor. You could see the same doctor, but you couldn’t sit in the front of the office. My father and mother grew up like that, so they were conditioned to follow orders. But when we were growing up we broke the rules. My brother, Monroe, was especially rebellious. He started going to the front and the doctor didn’t really say anything. But the norm was that you didn’t really do those things. And when you’re a kid, when you’re growing up, some of those scars last a lifetime. There are certain things I live day-to-day as an adult that have carried over from my childhood. You know, scars of racism and discrimination. That’s one of the reasons why I don’t deal with race in my work. I’ve had such bad experiences with that stuff that I just want to get around it and try to show just straight excellence. Take it for what it’s worth, like it or not, but I strictly base my work on quality, skill, intuition, and vision.

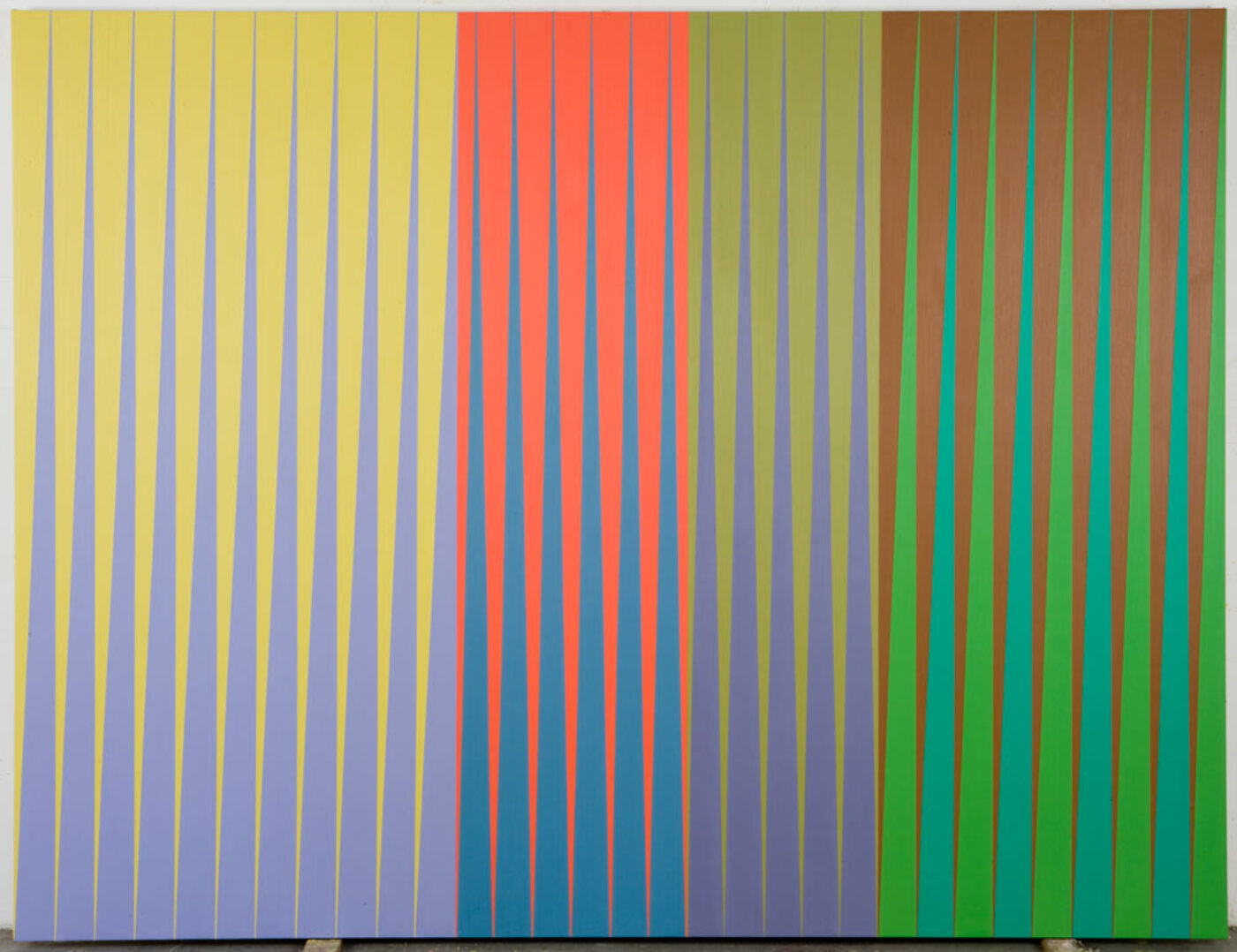

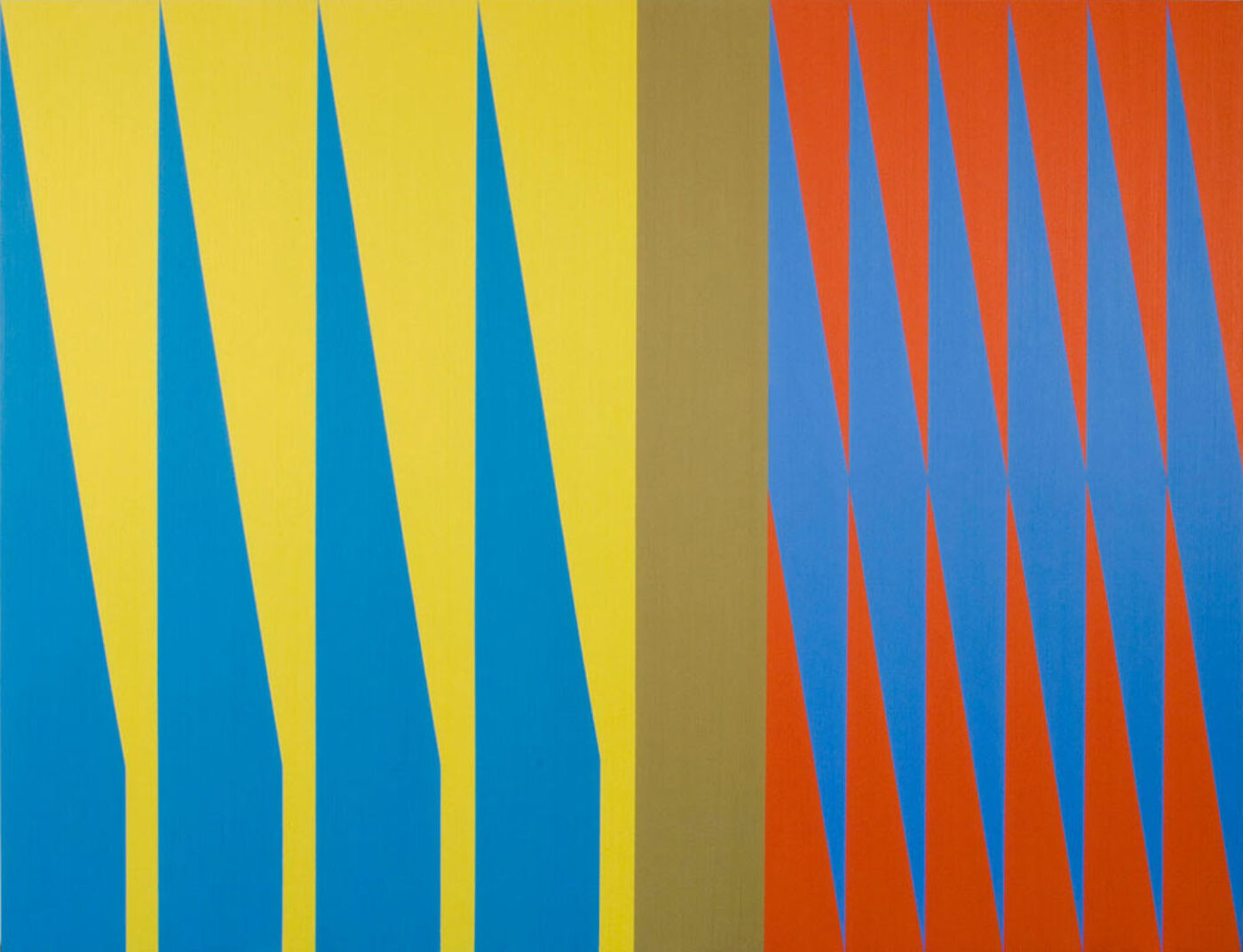

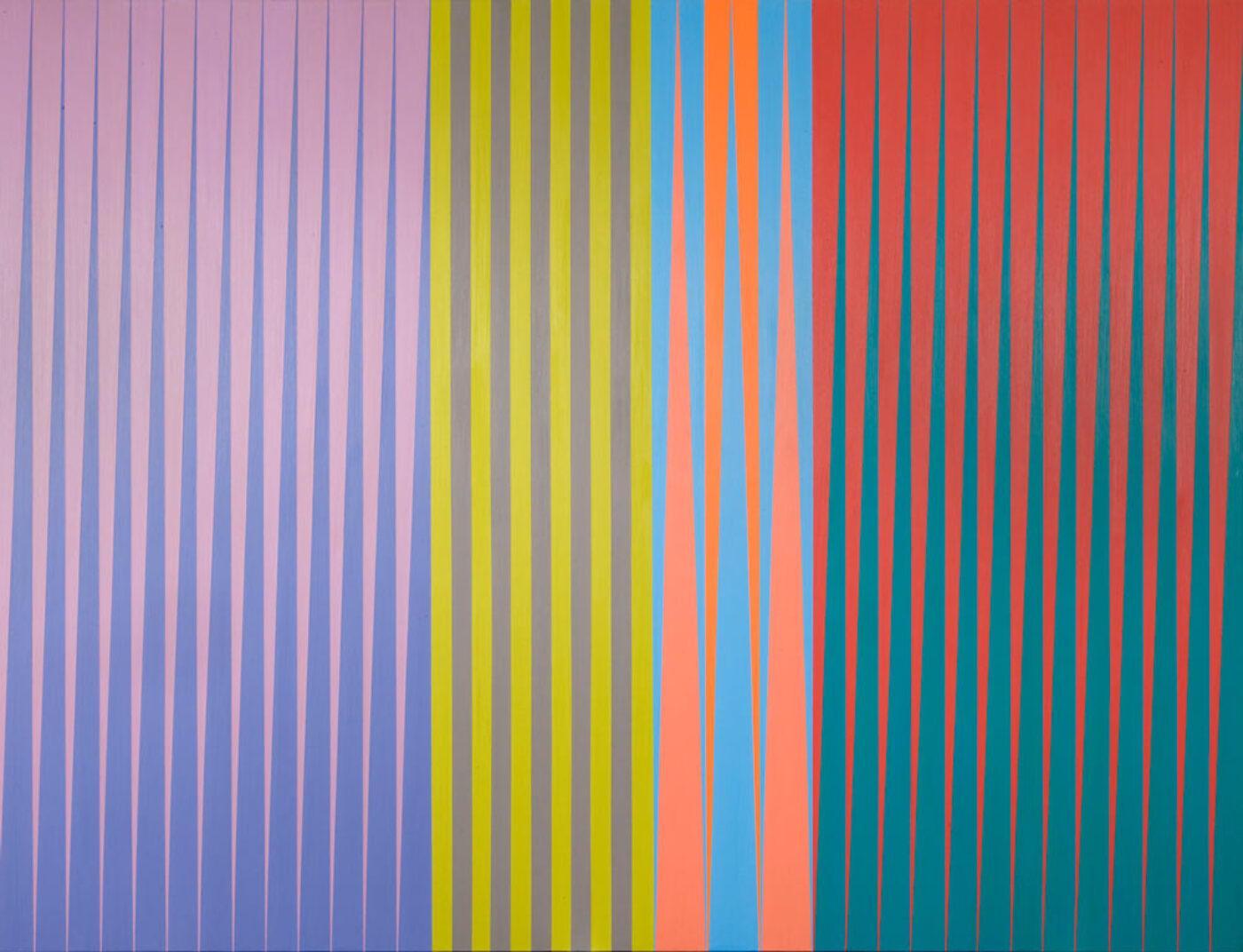

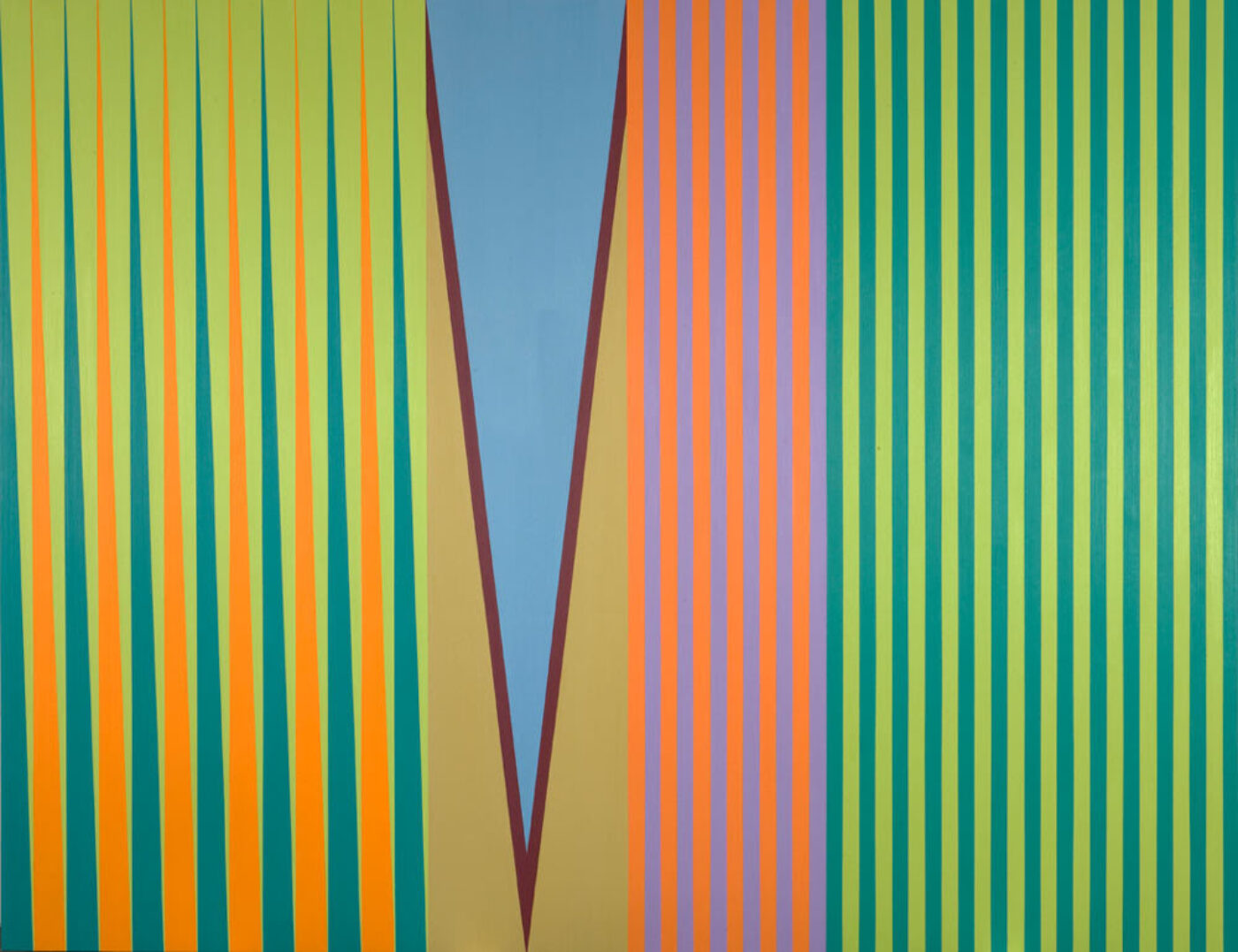

Portrait of a Star, 2001, oil and wax on canvas, 74 x 96 in.

But we’ve been fighting racism forever. I was sixteen years old when Dr. King was assassinated, right in my hometown. Memphis is a city in the middle of the Bible Belt. It probably has somewhere between 1,200 and 1,500 churches. When I was growing up there was a church every two blocks, no matter what direction. So, you went to church. They were put there to keep the peace. When we went to church the preacher would tell us this, that, and the other. But during the week you were going out in the streets and getting abused. Even the churches were segregated. It was Dr. King who said that the most segregated hour in America is church on Sunday morning. That’s what we grew up in. And we had to invent our way out of this stuff with morale and community care. The most significant problem was that there wasn’t any built-in support structure other than the Church and the family. But a lot of families were in unstable environments. You know, people were in such dire straits. Alcoholism and crime were rampant. We used to fight a lot to protect ourselves because the police didn’t protect us. It was that kind of thing. So, I grew up a bit of a pugilist.

LPB: (laughter) That’s a good way to put it.

JL: But that’s the way I grew up. And, somehow, I stuck to art all the way through. My father started me out working with him in construction at an early age. I worked entire summers with him. I had about a week or two before school started for vacation.

LPB: So you acquired these real skills?

JL: Well, he taught me a good work ethic. And I do have some skills in construction. A lot of that skill went into my painting. So, that’s why you see the attention to surface in my paintings. I like to mix and make my own paints and colors. Because at all these construction sites when everything was done manually—mixing the mortar, for example—it was all done incrementally. So, some of that still informs what I do today in my work.

LPB It’s procedural: one thing after the other.

JL: That’s right. One step at a time. And then there’s the drying time for certain things. You had to wait twenty-four hours, thirty-six hours, forty-eight hours…

LPB: On the clock!

JL: But they were masters at it. Most of these people that did construction were black men; some were Native American. There were a lot of Native American groups and tribes in the South and Mississippi. My mother was a culinary master too. I mean nobody could cook like her. Nobody.

LPB: And that takes time. It’s a procedure.

JL: And it’s protracted. She learned a lot of stuff by reading cookbooks, but she always made the food better. She added something to it. She put her signature on it, her stamp on it. And she was very popular as a result. She would sell cakes to the church. Basically, she just made this stuff for us, for the kids. There were like seven of us. And we grew up eating like kings and queens, no matter what it was. It could just be beans and rice and it was amazing.

LPB: That’s creative activity.

JL: It’s very creative. And my grandmother was a seamstress. My grandmother, Ruth Smith, was probably no more than a generation, maybe two, removed from slavery. She grew up as a sharecropper. It was indentured slavery; they were cheated out of everything. Most of them had very little education. But they had a lot of practical knowledge—common sense.

LPB: My parents are from Alabama.

JL: So the survival instinct is there, even when they used to talk to us about the Depression. When the Depression hit, all of the millionaires in the North were jumping out of windows. But for black folks the Depression was like a little soft sucker punch because they were fully prepared for it. They lived it. They are still living it. So, it didn’t really affect them as much.

LPB: Survivors.

JL: That’s right. This was their life. What these people were calling the Depression was what black people were living day-to-day, every day. And they were just looking forward to going to church. All my father and his gang were looking forward to was drinking on Fridays after work. But I come from the deep South, and the deep South is still… It’s made some progress, but it’s still a very racist section of the country. And they show it with their Confederate battle flags, race killings, and guns.

LPB: Had you seen any paintings or any art while you growing up in Memphis?

JL: I think it was the paintings of Thomas Eakins that I saw in an encyclopedia. My mother bought a bunch of books when I was younger. So, I was primarily exposed to reproductions and illustrations. The museums in the South were second or third rate. They would have derivative examples from private collections from all over the South. You know, a lot of it was regional. I didn’t really see any great painting until the ’70s when I went with my school to visit the Art Institute of Chicago. Before that I was just copying old masters from all these books. And then I started setting up still lifes to work from.

LPB: So, your parents allowed for your creative activity to be in the house.

JL: Yeah, I had a little room upstairs that I could go up and paint in.

LPB: That’s pretty amazing. So, you had a studio.

JL: Well, it was actually a bedroom that I turned into a studio. It was my sister’s room. It was small and intimate. It had a little window. And I would just go there all the time.

LPB: How long before you started showing your work to other people?

JL: Well, I started getting some praise from my family. When I went to school my art teachers noticed my talent.

LPB: What school was this?

JL: I went to several schools, but it was at Hamilton High School where I had my best teacher. His name was Ivory Walker. He was a guy that knew how to take talent and nourish it. He was a good teacher and a good role model. And when I graduated I was accepted to the Memphis Academy of Art in 1970. It was probably the most integrated situation I had ever been in, but this was after Dr. King was killed.

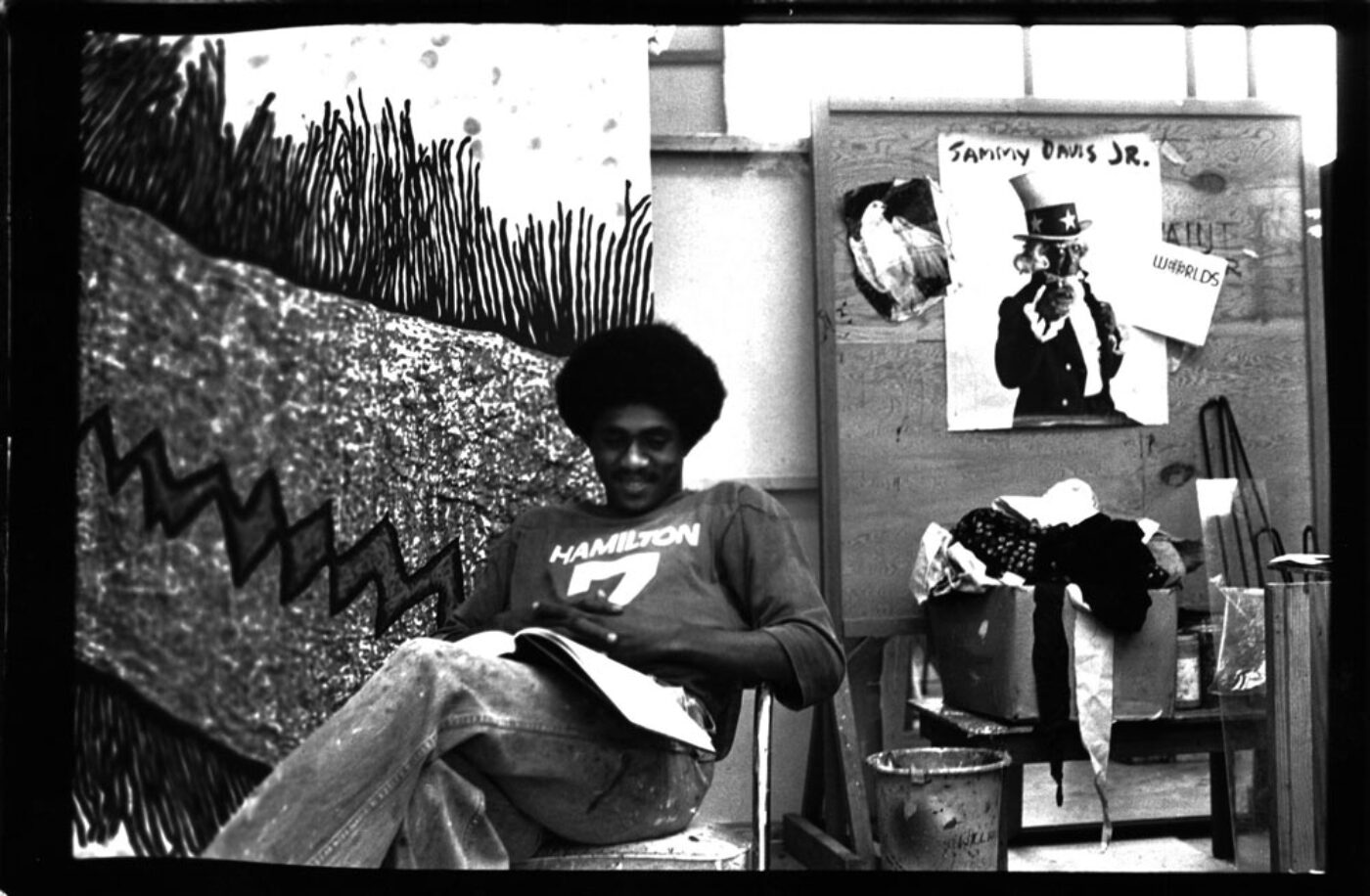

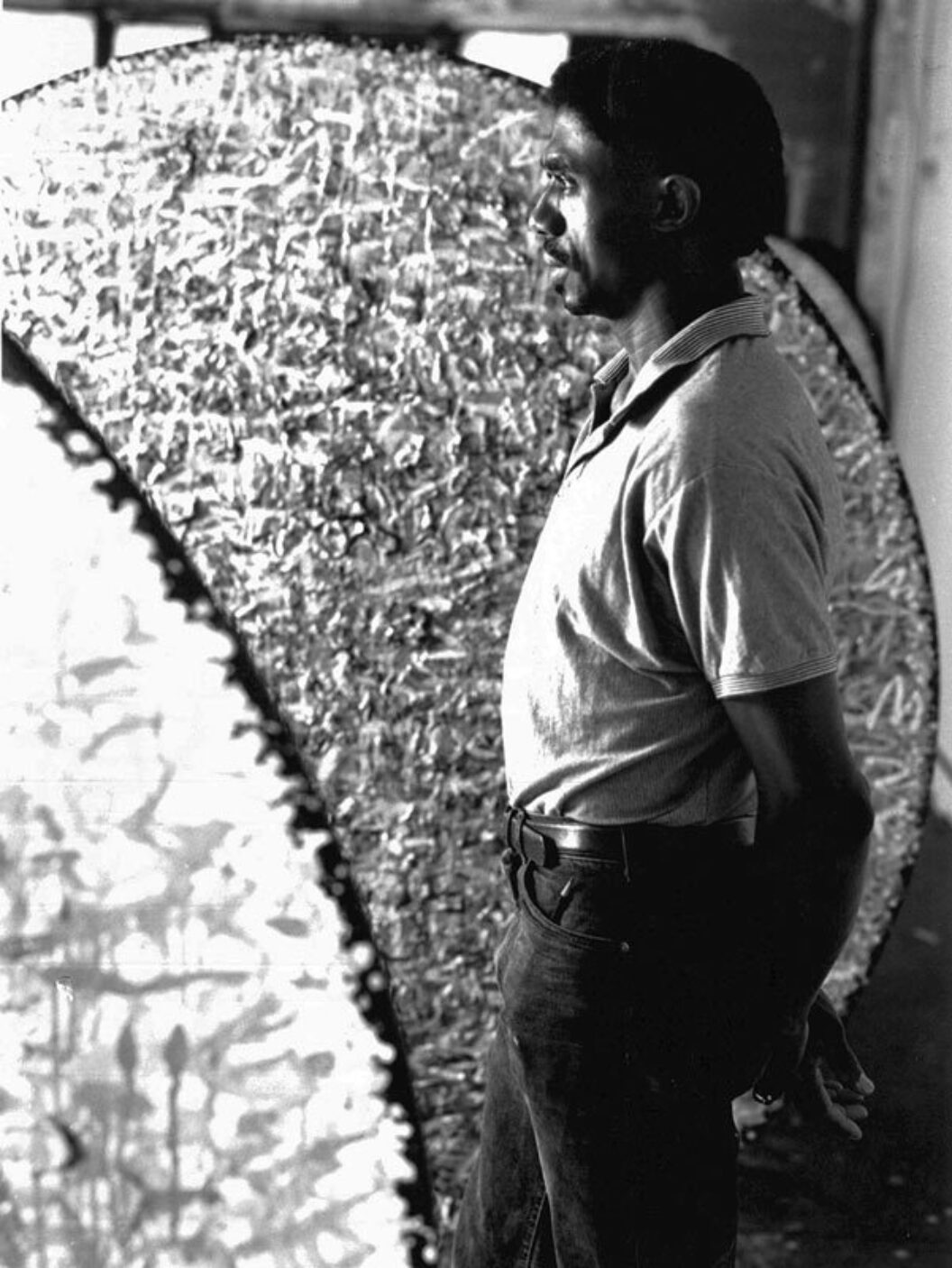

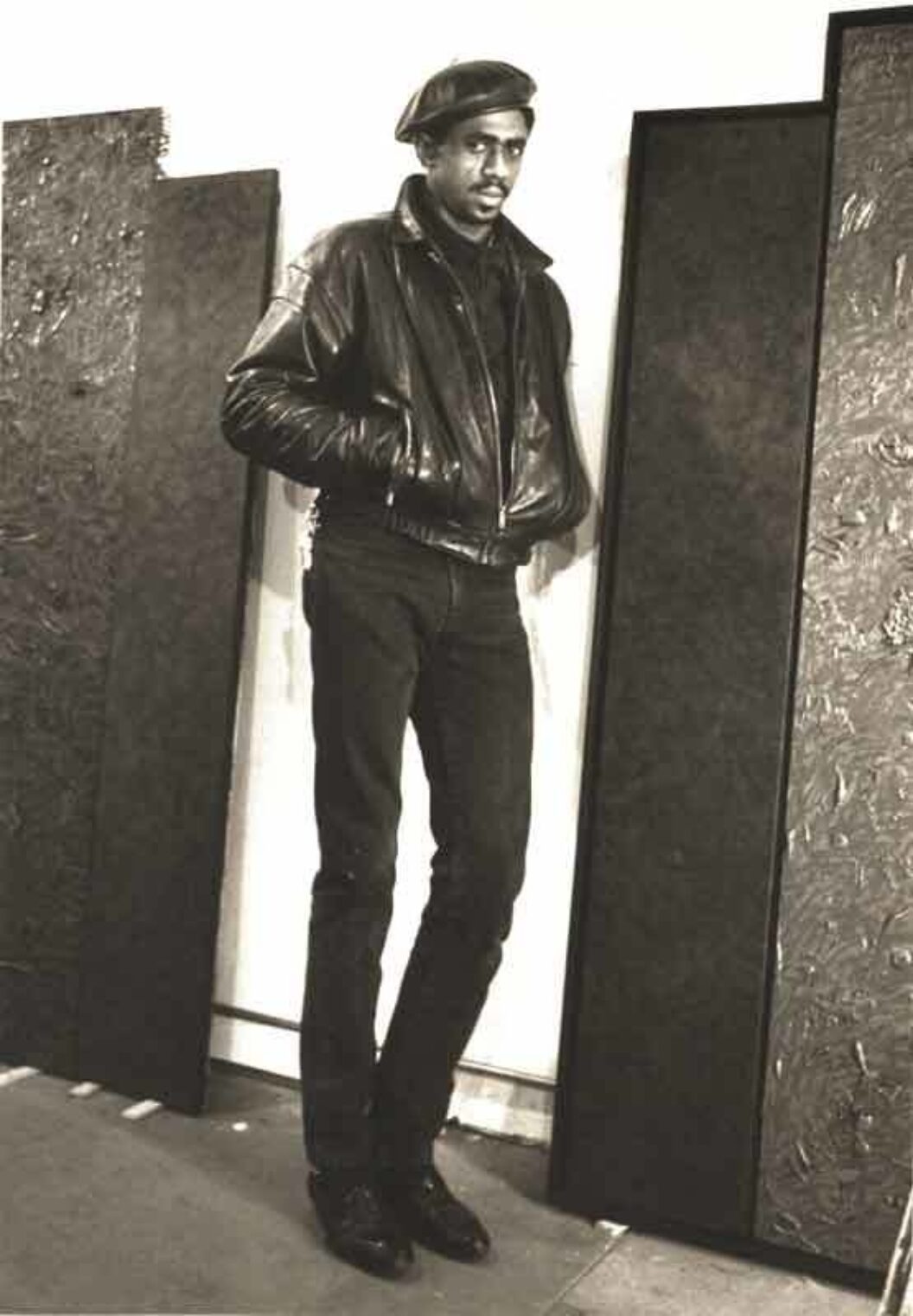

James Little in Memphis, 1971. Photo by Nancy Bundy.

LPB: So what was that like? Dr. King was assassinated and here you are in this integrated school for the first time.

JL: Well, there was a sense of urgency. I mean a lot of blacks went to school during the ’60s and ’70s, no matter what people tell you. Right after King was killed there was this national urgency to get us into these institutions ‘cause everyone was pissed off, and it was very volatile. And if we weren’t going to be in school we were going to be doing something else. And we had been denied entry into a lot of these places. When I was growing up there was this park right next to where I was going to school. Black people were only allowed in that damn park on Tuesdays or Wednesdays, I can’t remember, but only one day out of the week. And then when integration came through we had a mayor named Henry Loeb who decided to close all the swimming pools so that the black kids couldn’t swim with the white kids. As a result, you got a generation of black and white adults in the South that can’t swim. (laughter) And so it was that kind of thing; it was endemic and silly. And that’s why I’m so cautious when we entertain race the way we do. If you’re doing good work and you’re doing scholarly work, and you’re doing the very best that you can do, you will be noticed. I don’t know if people really care whether I’m black or not. I think society as a whole acknowledges race and racism, but I don’t think, over the long term, people really care. People always return back to their bad habits.

LPB: So here you are in the world, starting to get acclaim for your work. Did that start in high school?

JL: Well, I won a few awards in high school. But it didn’t really kick off until there was a big time critic, Gerald Nordland, who acknowledged my work. He’s still alive by the way. He was the chief curator of SFMOMA. So there was this big exhibition at the Arkansas Art Center, where they invited curators from all around the country to select works by southern artists—Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas… And so all these artists would enter their work to be considered for this show. Up to that point not much had happened. Though—when I was in art school—I had some really good teachers, but a few of them were bigots too. Some of them I still don’t like to this day.

LPB: What would they say about your work?

JL: Some would say some insulting things that went beyond the pale. But I was there to get a degree. And people like that try to discourage you. Another problem is that you don’t have many role models that you could take your problems to. It’s like calling the police on the police. Anyway, what happened is that Gerald Nordland came down and curated the 16th Annual Delta Exhibition at the Arkansas Art Center in 1973. And one of my professors was there and called me all kinds of names—I think he called me an insensitive clod.

LPB: That’s strong language.

JL: It was strong and I was pissed off. Believe me, like I said, I was a pugilist. I really wanted to kick his ass. But I was in school trying to get a degree. When Nordland put up the show, he chose a painting of mine from my sophomore or junior year, and the painting won the top prize. This is when I was at the Memphis Academy of Art. It’s called Memphis College of Art now.

LPB: What kind of painting was it?

JL: It was an abstract painting done in oil and wax. I had just started doing oil and wax paintings in 1973. The title of it was Umber Drift #1 and it was five by seven feet. Big painting. And I won the prize. Up to that point I had gotten an A in maybe one or two classes. But I hadn’t gotten any A’s in painting or anything like that. When I got the award, I started getting all A’s in everything. So after I got the award, I went back to the guy who called me an insensitive clod and said to him, “It’s amazing what an insensitive clod can do isn’t it?” And that destroyed him immediately. He melted right in front of my eyes. So, I’m just saying that with patience and time, if you stick to it and you believe in what you’re doing, no matter what the outside forces are, you’ll come out on top. That’s what I believe.

James Little in his studio at the Memphis Academy of Art, 1973. Photo by Nancy Bundy.

LPB: It seems like the work ethic that you learned as a child… You started making the thing and you kept at it.

JL: I do it until it reaches fruition. And I know when I get it there. I change things rarely. If I screw it up, I throw it in the garbage. I want quality in art. I respect all forms of art, but I’m not really interested in a narration of what the thing is supposed to be. I don’t want to know. I want to make that decision on my own. I want to see what you’ve done, how you’ve organized your space. How you’ve treated space, color, and your subject matter. I want to see how it connects to the art of the past, see what you bring to it and what I can learn from that. But in today’s art world it’s different. So, I just stick to what interests me. Good design is fundamental to my art. In my later years, I began to appreciate the Neo-Plasticists and the Constructivists, and that’s the kind of art that seemed to make the most sense to me. Piet Mondrian and El Lissitzky. I also like some of the American Color Field painters like Ken Noland and Alma Thomas. And I like Jacob Lawrence and Stanton Macdonald-Wright. Not so much the storytelling, but just the way they organized the damn pictures.

LPB: Well, even with the figure, the structure in Lawrence’s paintings is just so strong. It’s important.

JL: It’s as important as the figure.

LPB: Sometimes I don’t even consider those figures as actual beings, but more or less structures brought into a sort of human image.

JL: That’s right. They are structures and they’re flat. And the other thing I’ve tried to do is figure out ways of flattening the picture and keeping it flat. You know, when I went to Syracuse University—that’s where I got my MFA (1976)— I studied up there, had seminars with Clement Greenberg and I met Hilton Kramer too, among others. I know you know Greenberg, but Hilton Kramer was the art critic for The New York Times. He passed away some years ago. But you know, I was in a critical thinking environment. They didn’t really talk so much about painting as they did criticism, and the art criticism was what helped you develop your theories around painting: What it meant and where you wanted it to go.

LPB: So, who were your peers at the Memphis Academy of Art?

JL: There were many people there. I studied painting under Edward Faiers. He was from Canada and he studied under Will Barnet. There was also a sculptor there, a good friend of mine, Luther Hampton. He’s still with us. And there was also a painter named Veda Reed who taught me design and color. Carroll Cloar, who became pretty well known. He was a Regionalist painter. He chronicled the South and worked a lot in egg tempura. There were some quality artists in Memphis.

LPB So there’s this idea of leaving the nest.

JL: So I left to go to Syracuse University. They actually recruited me. I met the Chair of the Department, George Vander Sluis, who came to my studio in Memphis to see my work. He was very excited about it. He asked me what schools I applied to. I told him Syracuse was one of them. It was top on my list with other schools like the Art Institute of Chicago and Yale.

LPB: So why Syracuse?

JL: Syracuse awarded me an African American Studies Fellowship. They had a great painting department too. And they really wanted to make a difference. I mean they really wanted me. I was set. And you know all art schools teach the same shit. I don’t care what school it is. A school is not what makes you a good artist. Don’t get me wrong, school credentials are important, but when you get out into the real world it’s bare knuckle stuff. It’s competitive as hell. You gotta be extremely smart. You have to be resilient and you’re going to take a lot of hits. You’re going to get discouraged. But if you get in there and gain the respect of your peers, things start to happen. Everybody has an idea of what’s most important. Everybody has an agenda. When it comes down to this stuff, agendas go out the window if you don’t have success. If you don’t make good art, I’m not interested. It just doesn’t matter to me. I think it’s important to go to school and get good degrees, but when you’re doing things with your hands and the result is based on intellect and vision and talent, then you gotta come up with it on your own. A college or school is just not going to produce that.

LPB: What was Syracuse like at that moment?

JL: Well, it was a hotbed for art at the time. Like I said, Clement Greenberg was up there. Him and Hilton Kramer had symposiums and lectures. They turned out to be very similar. Sol LeWitt, Barbara Kruger, Elton Fax, Charles Hinman, Marilyn Minter, Bill Viola, and Robert Goodnough graduated from there. LeWitt would show up every now and then. A lot of big people came out of Syracuse. Peter Plagens, the art critic, was there. Star running back, Jim Brown was there. A lot of stuff that had nothing to do with art, like football player Floyd Little. You want to be associated with him though. I mean if you go to a great school and Jim Brown and Floyd Little went there, that’s a sales pitch. I wanted to be there. I wanted to be a part of that.

LPB There was a discussion going on, not just in art but the whole environment…

JL: It was critical thinking all the time. You don’t get that anymore in the art world. You just don’t get much of it. We need more of it.

LPB: So it seems there was this relationship between criticism and the arts that was much closer than it is today.

JL: And people expected it. Some of the best artists during that period were ones that came out of the world of criticism. It doesn’t just come down to a competition between abstraction and figuration, but really what your oeuvre is or was all about. And sometimes people would be hostile in their response. But I’ve never been one to believe in destructive criticism. But you get that when you’re out there. And to a large degree race also played a role in that. But I didn’t have much of a problem. Syracuse treated me very well. I sent two of my kids to Syracuse University. It’s a fantastic place. Probably the best place for me. I had everything I needed.

LPB: It seems like you found a home at Syracuse.

JL: It was even more than that. Top people in their profession were coming up there all the time. I had never been exposed to that. That’s what these big league schools do. Syracuse only accepted seven painters a year and it still does today. So to get in was no small task. The College of Visual and Performing Arts had Vanessa Williams, Taye Diggs, William Powhida, you name it.

LPB: There were a lot of talented people there.

JL: Yeah but a lot of it you didn’t see. You go there you gotta put your nose to the grindstone. And the environment during the winter is just brutal. There’s really no reason to be there unless you’re at the university. People don’t just move there to live in Syracuse. It was good for me and my top choice. A lot of things that I do today I developed while I was there.

American Dreamers Denied, 2011, oil and wax on canvas, 72.5 x 96 in.

LPB: Were you concentrating on painting full-time or did you have to do other things?

JL: When I was at Syracuse I was painting full-time. I taught voluntarily. I didn’t have to. They asked me if I’d be interested. I taught two classes in figure drawing the first year. The second year I taught Advanced Drawing. I had a strong background in drawing. I’ve also been back as a visiting artist.

LPB Were you in conversation with other students there?

JL: I was. I talked to a lot of students. I had one friend from Chicago. His name was Audubon Lucas. I don’t know where he is today. But he graduated before me. We were pretty close when we were in school. Some of the students were good people. But when you become a fellow in one of these places—this is one of the top awards they offer—students take notice. Sometimes people don’t take it too warmly. So I just kind of moved away from that. I’ve always been a private person, so people misinterpret my temperament as being arrogant or highbrow. The only thing I do is come in and try to produce the work that I do, which is extremely time consuming. I have to stay focused. I have to pay close attention to what’s going on. I mean this stuff doesn’t just fall from the sky. I have to think my way through it.

LPB: So people are bringing their own assumptions.

JL: In large part, but then you also have people in your corner who really want to see you succeed: your family, friends. There’s a lot of things that get into it. You know, basically I don’t like the art world… I love art.

LPB There’s a difference. I understand.

JL: The way the art world functions is nothing to be attracted to.

LPB: So the social aspect, the economic aspect—

JL: I just can’t do it. I don’t need to do it. I had several opportunities when I first came to New York. I’ve won some big awards and grants: the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Grant (2009) and the Pollock-Krasner Award (2000). I made some big sales to important museums. Some great reviews and articles have been written about me and my work in Art in America, Art News, The New York Times, The Village Voice, and The New Criterion, among others. I’ve done quite a bit of stuff and it’s still ongoing. I have a big project going on as we speak.

LPB: The commission at the LIRR Jamaica station in Queens. That’s where I’m from.

JL: That’s where you’re from?

LPB: Yeah, I’m from Rosedale.

JL: You’ll see it every day.

LPB: I live in Harlem now, but that’s where I grew up.

JL: Governor Cuomo just announced it. It’s a huge commission that I won. I was in another universe when I came up with the design. It’s unbelievable that I won it. So it’s going to be out there, and I think they say 4.2 million people a week go through there. It’s quite beautiful.

Rendering of James Little’s colored glass installation for the MTA Jamaica Station commission, 2016. The project is scheduled for completion in 2019.

LPB: But you also have artists who are primarily social animals.

JL: That’s right. They are not good artists. But if you want to make headway, you do this full-time. You can’t have a rest at this.

LPB: Who was the first person, whose opinion you respected, to look at and value your work?

JL: Well, I can’t say that there was only one person, but probably at the top of my list is Harold Hart, who was the director of Martha Jackson Gallery back in the ’60s and ’70s. He was black. He hung out with Bob Thompson, Joan Mitchell, James Brooks, Willem de Kooning and others. Martha Jackson was one of the top five galleries in the world at that time. They had de Kooning, Bob Thompson… Ronald Kuchta, who was the director of Everson Museum in Syracuse, also admired my work. When I was at Syracuse he gave me a show at the Everson Museum before I graduated. After that I moved to New York City. I asked Ronald what I should do and if he had any contacts. He told me to go see David Anderson at Martha Jackson. “Tell him I sent you,” he said. I went to see David, who is Martha Jackson’s son. He said, “Well go and talk to Harold.” So I went down to see Harold. We talked and he liked my work. He said, “I want to see it in a year.” I mean, when somebody says that to you, a year is like a fucking lifetime.

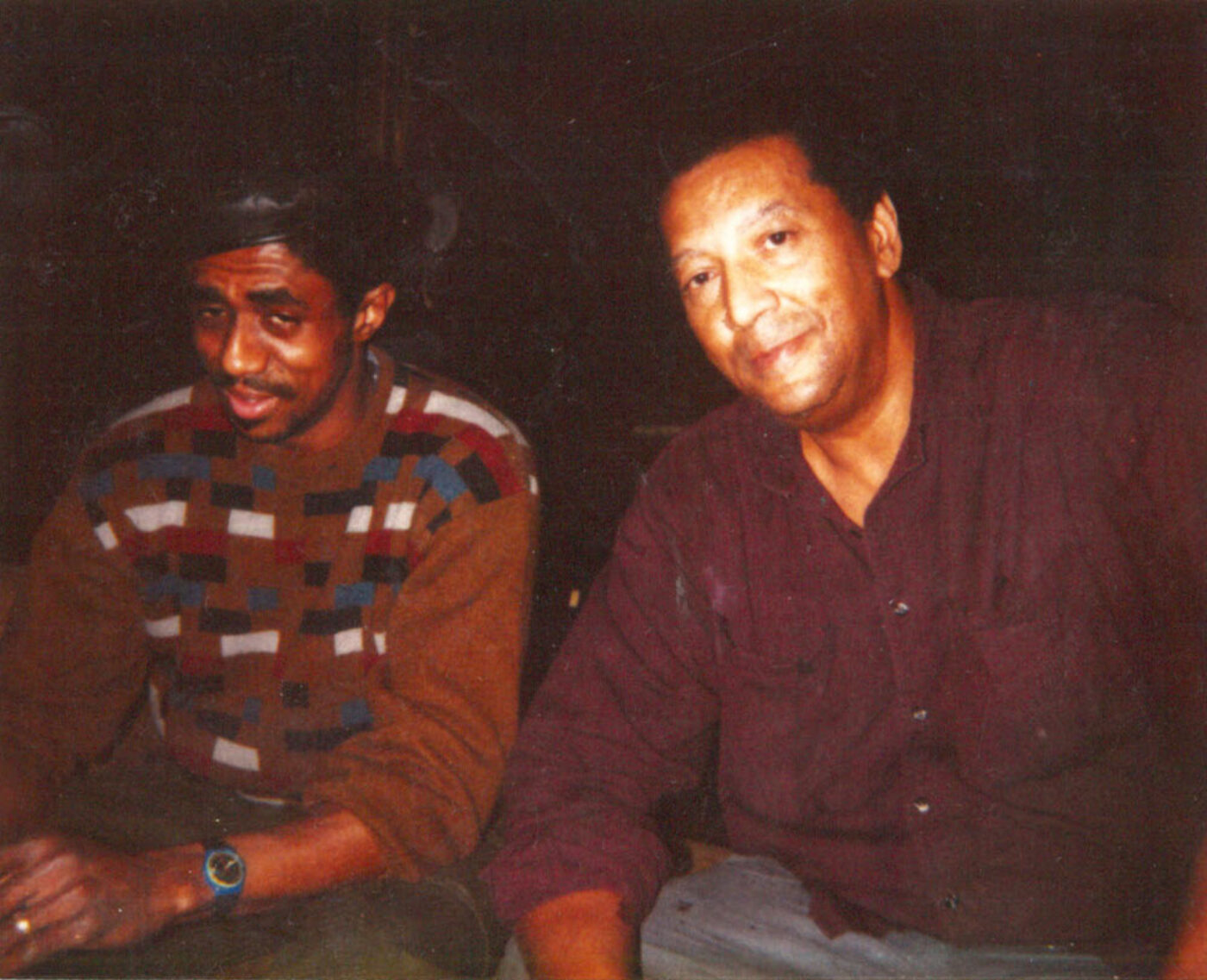

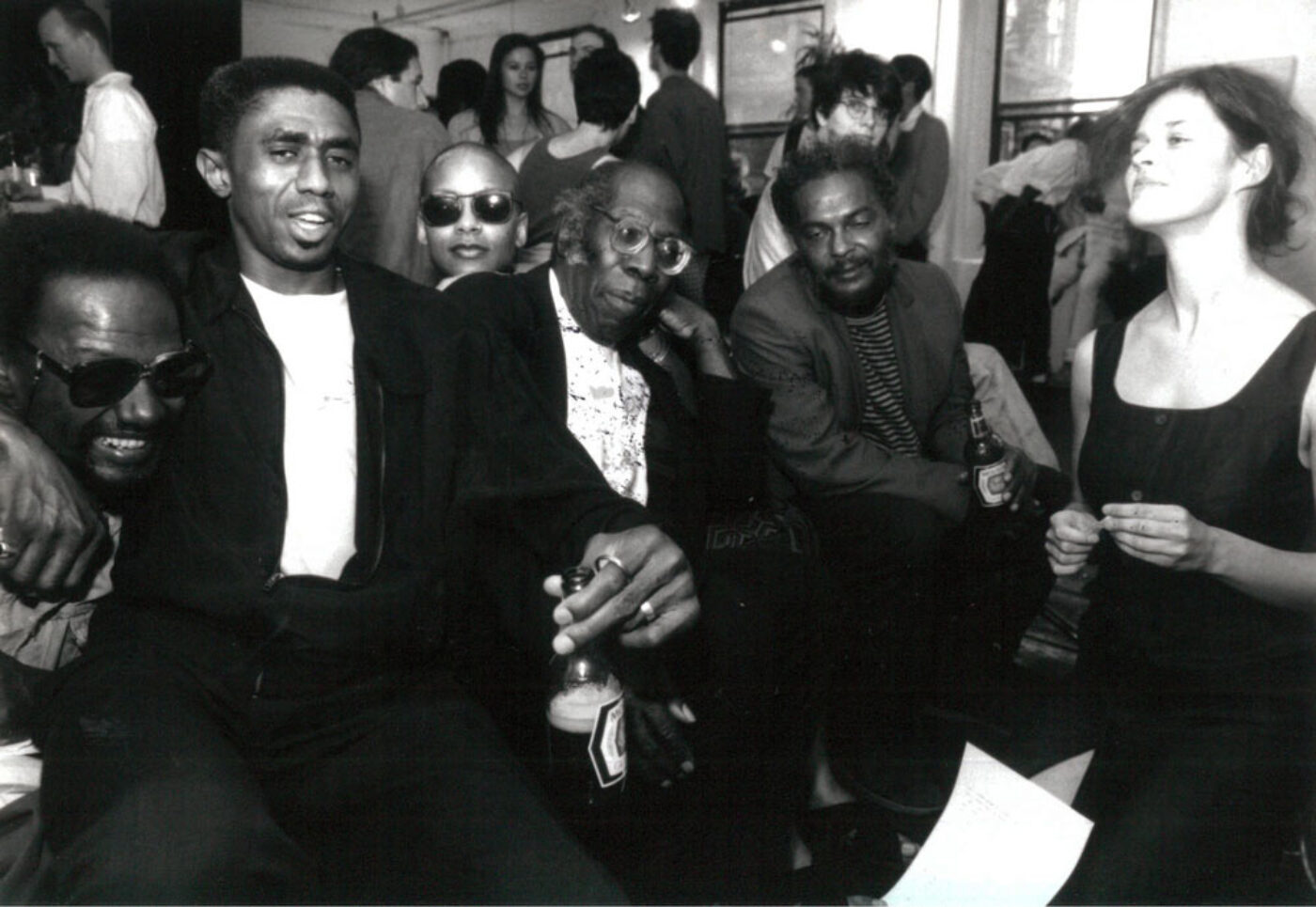

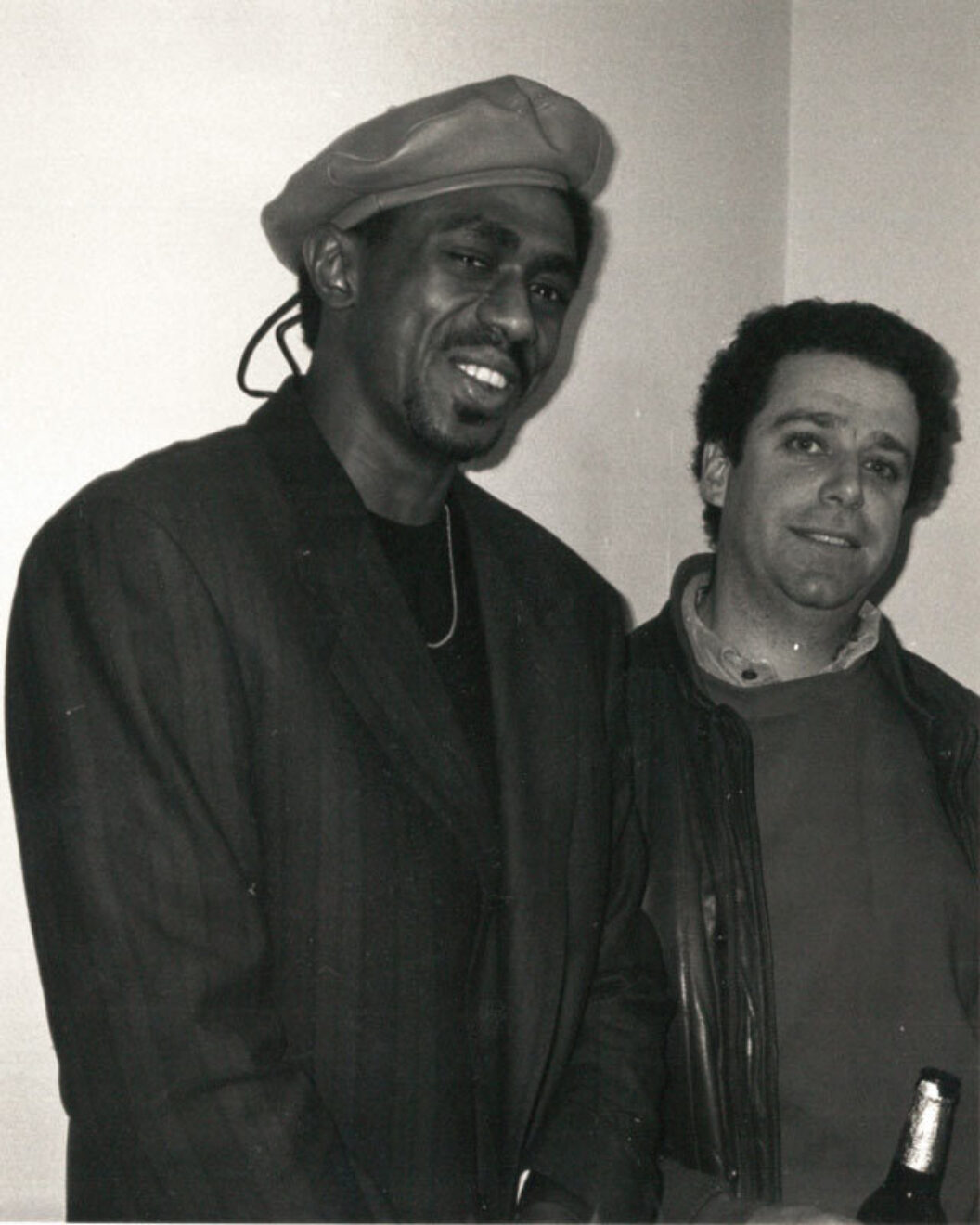

L to R: Harold Hart, Fatima Shaik, and James Little in Lyon, France, 1982.

LPB: (laughter)

JL: Are you kidding me? So I needed a studio space. A friend of mine, Manuel Hughes, he lives in France now. He’s a black artist. He said, “Look I have a student that has a space that she can’t afford and she wants to share it. And I said, “Okay, I’m interested in that.” So, I went over to meet the student and I said, “I’ll take half of this space.” It was on West Twenty-Fifth Street, top floor, 12,000 square feet. There were other artists up there, too. And that’s where I met Al Loving. We became life-long friends. So, Al and I hit it off. And Al liked my work when he first saw it and I liked his. But Harold Hart was probably the single most important person at that time for me. The other person was George Vander Sluis at Syracuse, the chair and dean of the painting department. When he saw my work, he immediately responded to it. And he went out of his way to get me there. He really did.

James Little and Al Loving, ca. 1986.

LPB: Was your work then similar to what it is now?

JL: Some were geometric and others were very organic and playful. I was building up really thick surfaces. I was using baby diapers and stuff. And I was using commercial paints over gesso, and then I would pour wax over it.

LPB: So it was three-dimensional.

JL: It was relief. It was paint over fabric paper—very robust painting. But when I left college, I stopped doing that. I was just painting. And they liked the ones that I came in with and even liked the ones that l left with. But George Vander Sluis was very important to me, as well as Harold Hart. And it was very important to meet Al because he knew everybody. But the most important people in my life were my mother and father, in terms of how far I’ve gone with this. But I’m just getting started. I got to finish this thing off right now in Queens, which is the biggest project that I’ve ever dealt with. It’s huge. There are forty-six windows, and they’re each seventeen feet high and about three-and-a-half feet wide. I have these engineers, these contractors working with me.

LPB So how long do you have for the project?

JL: I mean I’ve done my part. I’m waiting for the drawings. Once we get the dimensions, I’m going to be flying to Germany. We plan to have it installed by 2017–2018. And I think we’re going to make it, because we have to. We don’t have a choice. It’s been a circuitous journey for me. I’ve shown at the Studio Museum in a couple of group shows. But I’ve never shown in any of the major New York museums, which is ridiculous. Not the Whitney, MoMA, or the Guggenheim. I’ve shown at the Newark Museum, the Alternative Museum, the New Jersey State Museum, Everson Museum, Frans Hals Museum in the Netherlands, the Brooks Museum of Art in Memphis, the Studio Museum in Harlem… Kellie Jones did a show with Alison Saar, Whitfield Lovell, and myself called New Visions back in ‘88 at the Queens Museum. I’ve shown all over the country.

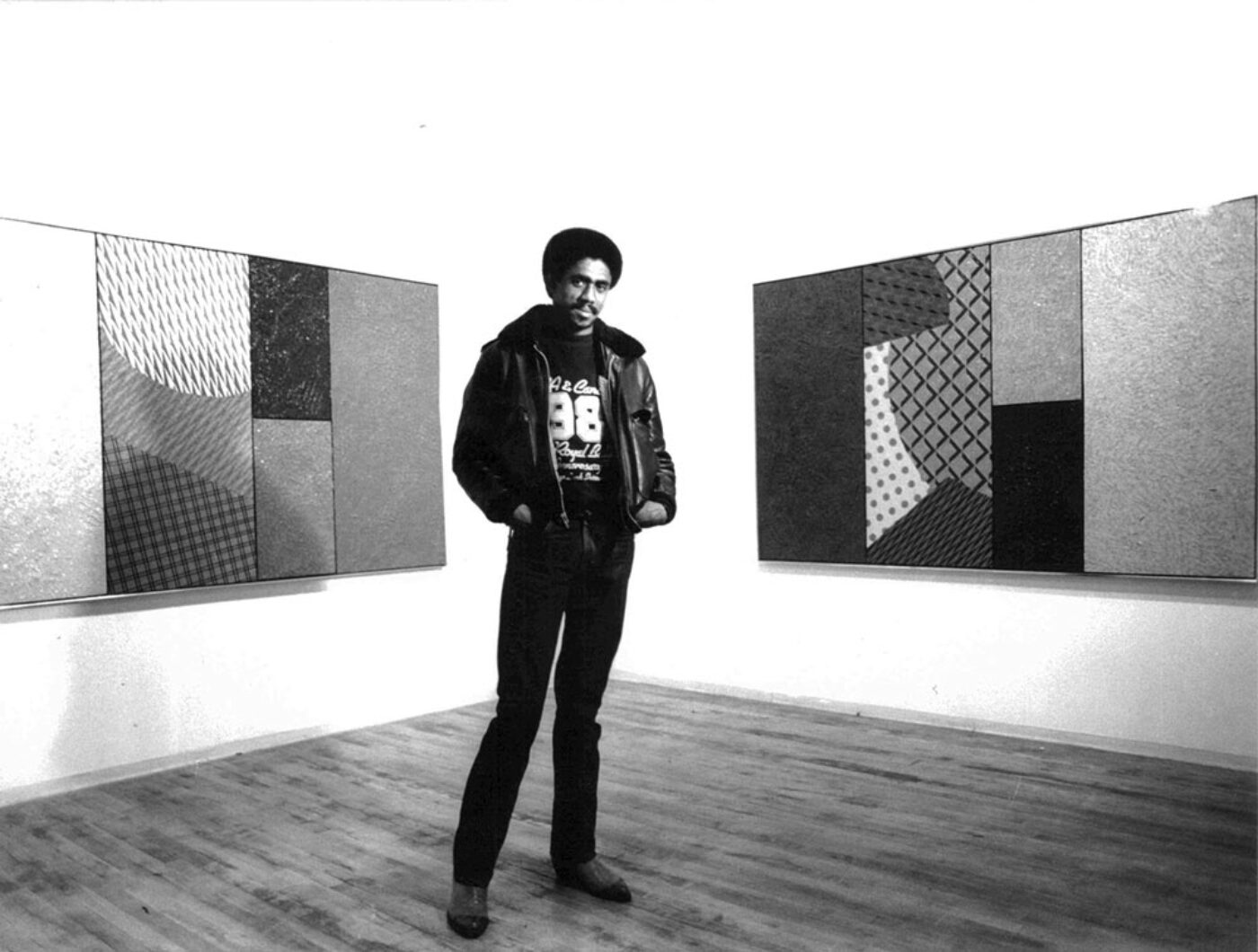

James Little at the Alternative Museum, New York, ca. 1984.

LPB: Yeah, I remember that show at the Queens Museum. I remember the catalogue.

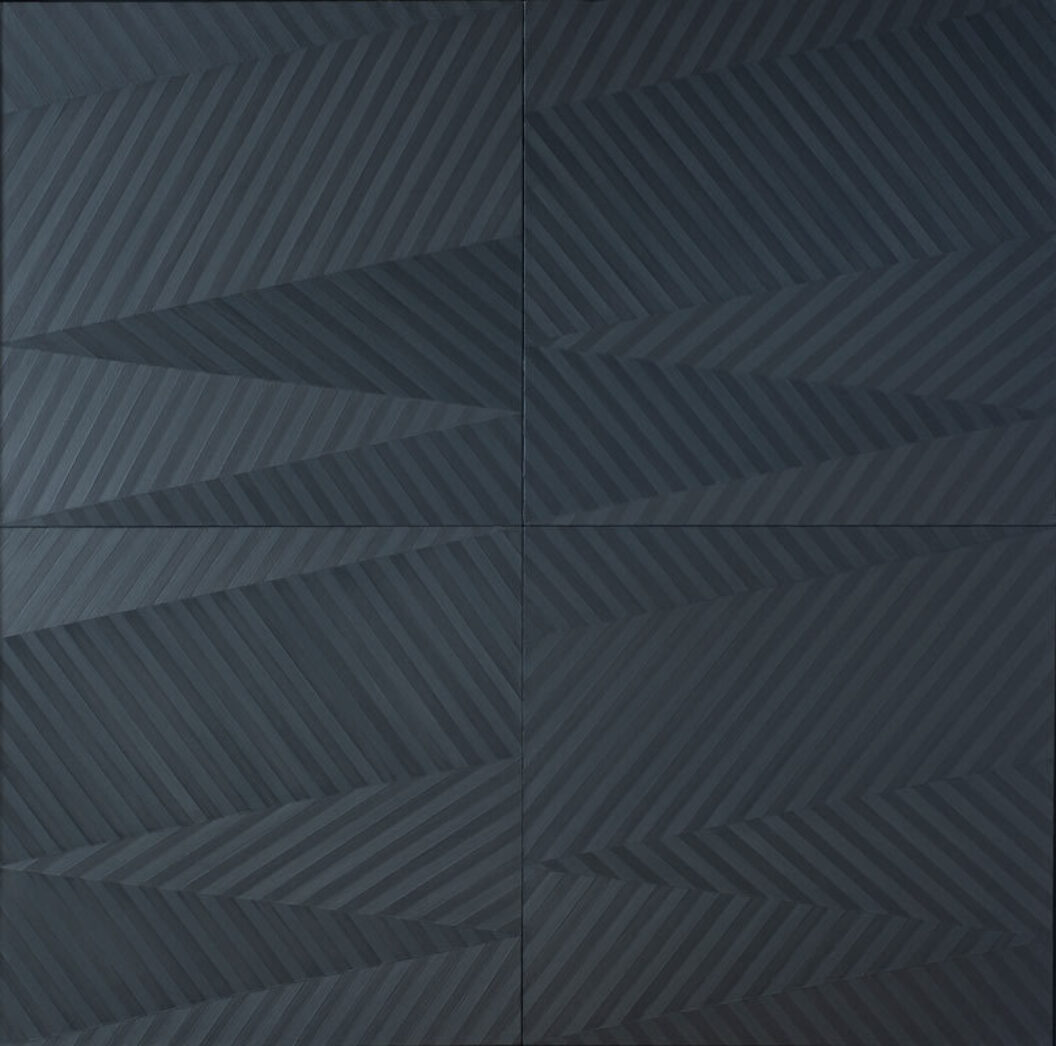

JL: Kellie put me in the show Malcolm X: The Man, the Meaning, the Icon at the Walker Art Center. I did a series of paintings way back before the X thing… before the movie, before all of that. Kellie knew it and decided to show my X paintings. So I’ve always dealt with politics and sociology in that kind of way. But it’s never been something that was the subject matter of my work.

El-Shabazz (C), 1985, oil and wax on canvas, 24.8 x 24.8 in.

LPB: So history—it’s around the work but it’s not the concern of the work, specifically.

JL: They are separate things. One doesn’t dictate the other. History is very important. Make no mistake about it. I remember one of the darkest days in my life was when Dr. King was assassinated. And if I was going to entertain something like that, that was the time to do it. But Dr. King was trying to get the best out of us. That’s what he was talking about. It was about excellence, content, character and self-motivation. I think he said, “If you can’t walk, crawl, as long as you move forward.” It was inspirational. And the only thing I really know how to do is make paintings. I want to give you a show, an experience you’ve never had. To show you ways of painting that you hadn’t thought about before. I want to address the history of art. I have a painting called Picasso’s Funeral (2006) and I was down in Texas and one of top dealers there walked up to me and said, “Why did you name that painting ‘Picasso’s Funeral’?” And he was a little aggressive in asking me that. I said, “I’ll tell you why. Because I’m trying to get around that motherfucker. That’s what I’m trying to do.” That guy is so big I’m still preoccupied with him. And he’s been in the ground for twenty, thirty years or whatever. That’s what I’m trying to do. That’s where I want to be.

Picasso’s Funeral, 2006, oil and wax on canvas, 76 x 98 in.

LPB: He’s in the ground but you’re still trying to make him fall asleep. (laughter)

JL: That’s right! Another nail in his coffin. Because he was that important, historically. So that’s the kind of stuff that I’m addressing. The only way I could fight it is through excellence. And believe me, I am politically conscious and pissed off about a lot of this stuff that’s going on as much as anybody. If I wasn’t painting I don’t know what the hell I’d do, because I act out my violence in my art. And a lot of other sensibilities. But I can’t allow situations like that to get in the way of my aesthetic intent. If the situation changed overnight, and we had a utopia, where there was no more racism, there were no more police killings, and everybody got along, I’d be preoccupied with that kind of subject matter in my work. What would I do then, paint a perfect world? I mean that’s not what drives me.

LPB: You’re conscious of it, but it doesn’t define who you are. And you’ve experienced enough of it in your life, more than most.

JL: Absolutely. And my wife, Fatima Shaik, is from New Orleans. Louisiana, Tennessee, Mississippi… I mean these were some hellacious places. They really were. And poverty was the key to a lot of the oppression. Keeping people down and that kind of thing. But I experienced it and I’ve tried to move away from it and try to address it through my art. And it’s turning out to work that way. But it’s still all done in solitude. I don’t have any assistants. Everything I do starts from scratch, from the bottom up. My hand touches every phase of the work. Even when people try to restore the painting I say, “Don’t do it. I’ll take care of it.”

Fatima Shaik and James Little in Paris, France, 1982.

LPB: And you’re right at the point where you understand your own intent. And you understand where the work is going, and what it’s about.

JL: I’m comfortable in my own skin. I look at the different categories that they put people in. And I talk to people about it all the time. Take Jeff Koons’s balloon dog. Somebody will pay fifty million dollars for it. You start talking about all of the African-American masters: Roy DeCarava, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Alma Thomas; you take everybody together and it doesn’t even come near that amount. So, I don’t take my eyes off that kind of thing. I’m going to get what I’m going to get, but I’m going to get it standing. I’m not going to get it laying down.

LPB: (laughter)

JL: It’s like the segregationists said when I was growing up: “Blacks have to make their own way.” So the art world was a lot like that. You have to make your own way, by and large. And you can make it if you get lucky, if people are impressed by what you’re doing. It happens to some artists. There are always outsiders, those who are always living on the edge of popular culture. And those are the ones—the sleepers—who you have to look out for because some of the greatest artists in the history of art have been sleepers.

LPB: What do you mean by “sleepers”?

JL: People that go unnoticed throughout their career, but are mostly respected among other artists. There were certain artists, like Johannes Vermeer or William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who were well-known, part of the elite, and enjoyed a lot of success throughout their career, selling a lot of work to the very wealthy. But there were a lot of other painters that were making incredible work who weren’t part of those social circles. There wasn’t a whole lot of attention paid to these artists. Those are sleepers. But nevertheless, history usually corrects itself.

LPB: The Paris Salon exhibited mostly wealthy artists who could churn out a lot of paintings. They had a factory going on.

JL: Yes. The same way the old masters employed apprentices and assistants to make the work, artists do the same today. Like Jeff Koons, who I mentioned earlier, he does that exclusively. But there’s always someone in the art world who’s doing all the heavy lifting. You take people like Giorgio Morandi or Van Gogh or Horace Pippin or Bill Traylor. They went through their whole lives making great art and no one paid much attention to them. But they were respected by their peers. But then you have other cases where artists know how to work the market, how to be social, and build their careers from that. I’m not one of those people. I’m not good at that.

LPB: Is that something you want to do?

JL: No, it’s just something I’m not good at. I just prefer to let time do its thing. I mean I lay it all out in the studio. It’s everything. It has to be done that way. I don’t have anything else to say beyond the product, my work.

James Little in his Chelsea Studio, ca. 1989.

LPB: I mentioned the official Salon in Paris, but there was also the Salon des Refusés across the street. It was in the tents outside the official Salon where you had the sleepers, the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists, etc. You know, we were talking about Syracuse and Greenberg, and you being influenced by Greenberg as a graduate student. But you had certain critics who were writing in the Paris Review and later October in the late ’80s, who didn’t consider African-American artists to be part of the discussion. And so this idea of the outsider, as an artist who is participating in the major language of the time, abstraction, and you’re making great art within that language, but as an African-American artist you’re immediately considered an outsider.

JL: The present moment is like a renaissance for black artists and African-American art in this country, and I consider myself an outsider within that as well. Most of the tendencies lean toward socio-political content, installations, text, and what have you. I am not a part of that. If you’re not in sync with popular culture or popular taste at the moment, you’re always going to be somewhat of an outsider. But the thing I was trying to explain with Greenberg is that the kind of art that I like, the kind of art that I gravitate towards, has always been art that has theoretical underpinnings based on formalism and modernism; art that has never been about narrative. I’ve always tried to figure that out, and I’ve always taken an analytical approach to my art. I’ve always tried to reach in and come out with something that was experienced or imagined. I think when you look at art, you should feel and experience it. And when I say “experience” the art, I mean the aesthetic experience. If you’re not having an aesthetic experience, the work categorically falls somewhere else within the history of art. You know, there’s high and low art. People don’t like to say that, but it’s true. There’s great art and there’s good art, and then there’s art that’s not so good. When you say there were black artists working at the same time who were outside of the art world proper—which is a white-male dominated, Eurocentric world—some of those black artists weren’t very good. Some were very good, but of course not all of them. And it’s the same thing today. A lot of them still aren’t that good. But as I said before, in the art world the market corrects itself. And sometimes it will happen in your lifetime; sometimes it will not. But if it’s great art, it will prove its resiliency. That’s why we can look back and appreciate people like, again, Horace Pippin, Bill Traylor, and William Edmondson. Great artists.

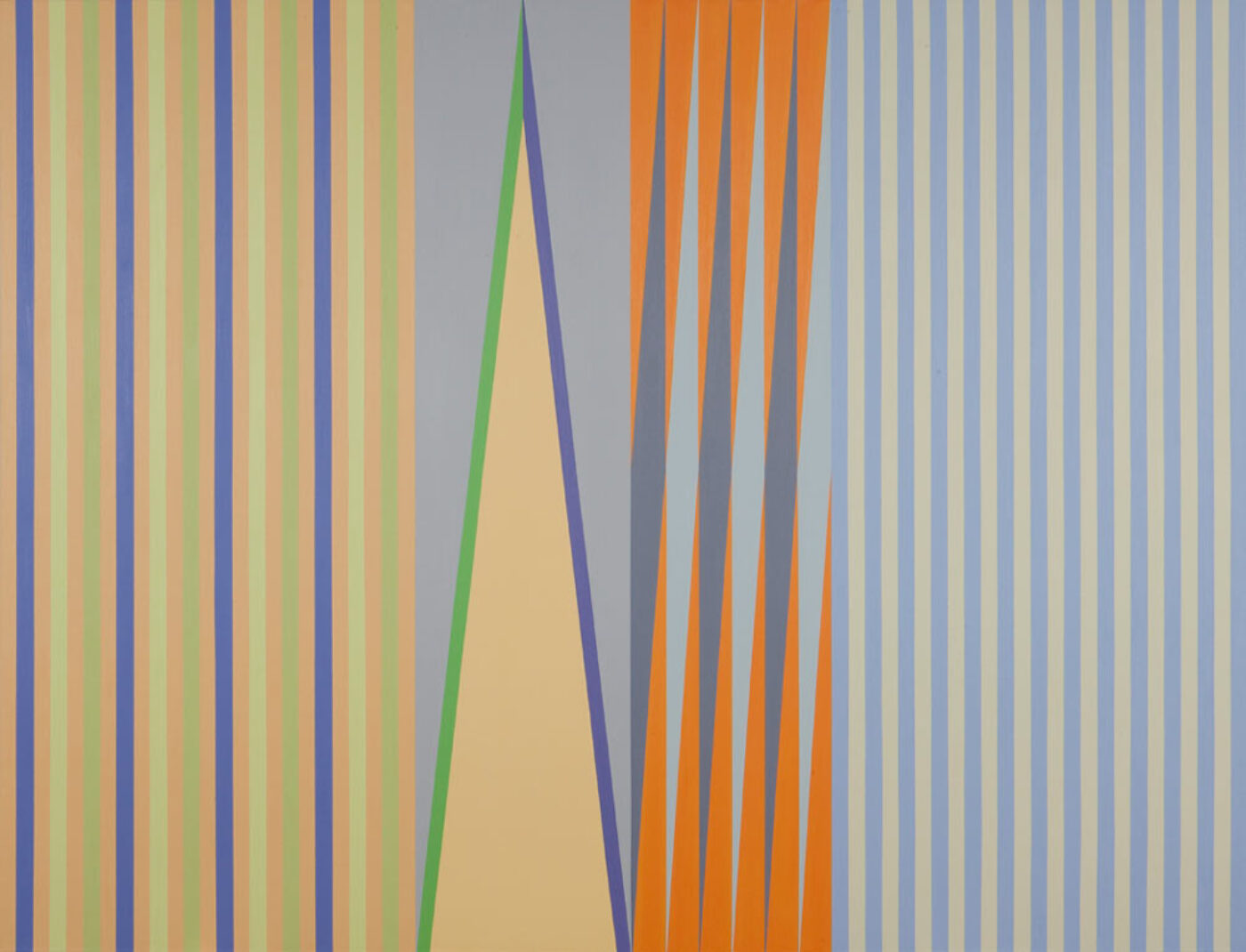

If Only…, 2010, oil and wax on canvas, 72.5 x 94 in.

But it wasn’t something economically driven. And don’t get me wrong, race was still at the forefront of all this. I had a guy tell me once, when I was in school, “You know you’d be rich if you were white,” talking about my work. This guy was a white guy from Mississippi who attended the school, and he was just being honest. I said, “Well getting rich is not going to be an issue for me.” I was just going to make the best art that I could make. But for him to say that, meant that race was still part of the issue. It’s never that far way. But I’m interested in making American art. I’m interested in trying to advance the way we see and experience art, especially abstract art. And I think the job of the viewer is either to accept or reject the experience. It’s always been like that for me. I know where my strengths are. I know I’m good with color. I know I’m good with design. I have a great relationship with the medium, the materials. I know the things that I primarily focus on. There are certain formal things that you have to do as you go along making paintings. And one of the more important things that I learned as a student, is that all these people that may be your heroes or artists you admire, when you leave school and get into the real world, those artists become your competitors. So, you have to try to get around a lot of stuff and continue to grow and look at art, and take charge of every opportunity that presents itself.

LPB: It’s one thing to be a student, right? But when you consider yourself a professional out there in the world, do you see your work in conversation with artists that you once looked up to?

JL: Yeah, I do. But sometimes the people that you looked up to when you were in school don’t excite you as much anymore. You could look at them and say, “This guy wasn’t as good as I thought he was when I was a student.” But sometimes artists gain recognition right out of school. But as you mature and you see how people move in and out of the art world, you realize that you have time.

LB: What do you mean when you say you have time?

Native, 2015, oil and wax on canvas, 60 x 60 in.

JL: Well, you have time to develop your work. You have time to spend with your work. You have time to explore your ideas. So the immediacy, when you’re young, to get it down, to make as much work as possible, is not necessary. You don’t have to do that. If that’s your forte, then that’s what you have to offer. That’s your style. Working fast and getting things done. Then that’s what you have to do. The main thing is to try to find your voice. And I found mine through a painstakingly long process. And I have all of these ideas about how I want things to look, my surfaces to appear, my design elements to relate to each other. All this stuff that I deal with basically comes out of a certain kind of formal strata, although it’s just information that I acquire through observation.

LPB: What I’m hearing, and correct me if I’m wrong, is that there are two different things going on. On the one hand, there’s the outside world in terms of the art world, it’s economies, it’s social relationships—you can see that moving in terms of people having shows and working to have all this kind of acclaim. But on the other hand, I also hear you saying that there’s a space that you need to make for yourself that’s not congruent with these larger concerns.

JL: That’s right. It has nothing to do with that stuff—shows, the art market. Those structures are already in place. And there’s no real entry, unless you do something extraordinary, you know. And that doesn’t necessarily mean you make extraordinary art. You have to do something extraordinary, and if you do that, then that’s your entry. In my case, I’m having considerable success. Things happen. I’ve had shows and I’ve gotten some great reviews. You end up in certain collections. There’s a buzz. People start talking about you. And then there’s a kind of demand for your work.

But the smart money and the critical eye always seem to end up getting their hands on things at the right time. Affordability has something to do with it too. A friend of mine once told me that “the best dealers and the best collectors are the ones that make the fewest mistakes.” Mistakes can be extremely costly in the art world. You go out there and spend a lot of money on something and if it doesn’t grow any legs, then you are taking a huge risk. So you to try to minimize the risk from the economic side of things. As a painter, you gotta have thick skin. You gotta take a lot of hits. And you have to know when it is opportune. But you can’t control the market. People will spend their money on whatever they want to spend it on. People promote whomever they want to promote. I have opinions about a lot of things that are not consistent with the opinions of many people in the art world. But it’s my opinion. I think that I’ve always felt that I was as good as anybody out there. I still do and that has always driven me. I mean, I don’t consider myself a narcissist, but I do see a lot of art. And I see a lot of abstract art. I’ve been doing this for a long time. I know what I’m doing and I know when it’s not being done well.

So to go back to your questions about my peers, you have to put yourself up against them. Somebody was asking me about figuration and why I didn’t do it. And I have no issues with figuration, but I said, “I just felt like if I couldn’t take it past Cezanne or Vermeer or Caravaggio, there’s no need for me to bother with it.” I found more opportunity, more self-determination, and free will through abstract thinking. Speaking of being African American, coming from a background where most of us come from, free will and self-determination are very important. So I determine what goes into my work. So that translates to me having a steady license to do these things I want to do. So a lot of time you talk about black artists not having or getting a lot of recognition; a lot of that is based on the issue of free will. If you succumb to public expectations, you must paint black images and subject matter. You see, I never thought about that. I didn’t go that way. I’ve always tried to move away from that. And I never looked up to the white artists either. If they were good at painting, they were good at it.

LPB: You think some artists are choosing the figure in an insincere way?

JL: I do. I think that it just seems to be a nice, juicy, and rewarding thing to do right now. Proportionally, the amount of figuration in the art world now, compared to abstraction or even, say, landscape painting, is insurmountable. The majority of artists are working in figuration. But these things change. There’ve been times where abstraction was more popular. And artists go back and forth between abstraction and figuration all the time. But the best abstraction comes from artists who have been driven and committed to it over a long period of time. This is not something that you just gloss over. Or something you decide to get into because you saw how it was done. It’s not like that.

LPB: So you could look at a figurative painting and say this person really wants to be an abstract painter.

JL: Or I could say this person is a really good painter. I was talking to somebody today about figuration and abstraction. And I said to them, “Well, the figurative artists that I know, in my time, that I thought were very good, were also very good abstract artists.” And some of them just changed. Some of them move from abstraction to figuration and vice versa. If you learn the formal issues that are required to make good art, and you have the skill set to move seamlessly from one discipline to another, then there’s not a problem. What I’m saying is that if you don’t understand abstraction, then you can’t make the move towards doing it. Or you could and it’ll be a disaster each time.

LPB: So to be a black artist making abstract work you felt like an outsider, even within the black community. So how do you deal with that particular relationship, insomuch as there are a lot of black artists making figurative work who are becoming more successful than black artists making abstract work today? And there’s a long history of black artists making abstract work, too. So there’s a tension there.

L to R: Steve Cannon, James Little, Ms. Pryor, Robert Blackburn, John Ferris, and Kiki Nienaber, ca. 1996.

JL: It’s a sociological issue as well. I was talking to my younger brother, Perry, who’s a Pentecostal minister. I told him that I won an award for my work, and I was kind of cautious when I got around to talking to him about it. I also did an interview with Artnews, and I said some things in there about race and aesthetics. I was a little reluctant and cautious as to how they were going to respond. But I always try to be very honest. So I told my brother this, and I was really surprised at his response. He got behind me. My whole family and the black community were just glad I was in the magazine. They were happy with what I said. They were delighted that I took the risk. You get this platform when you start talking about Malcolm X and Dr. King and the Black Panthers. And the people that help you get there are a lot of white folks. No doubt about it. Everybody helps you. It’s not a linear thing. But you get there and a lot of people will just say, “Well, I take the Fifth. I don’t want to blow this.” But at the same time, you got a whole lot people out there that just want to hear that voice. They want to hear somebody articulate that for them. A friend of mine called me up and said, “I’m just glad I know you.” I thought he was going to come at me with clubs because of what I said. But it didn’t work out that way. And that’s my whole point. We are all the same no matter what we do subjectively in our work, or no matter what story we tell. The whole thing I said about being alienated in the black community, that happens because sometimes people misinterpret what you’re trying to do or what you’re trying to say. Sometimes we have missions and responsibilities that come along the way—I mean further along, in the future.

Sometimes we have to do things that are more immediate. And if you have a strategy and you take your time, sometimes people just miss it. It doesn’t have that kind of urgency that the public wants. But you have to have a whole lot of confidence in yourself because to be a black abstract artist in the US—especially in the environment that we were in today—they look at you like maybe this guy is some kind of freak. “I love his work but he must be some kind of weirdo.” But that’s not the case at all. Everything that I do you could find in black culture, in African culture. One way or another. You can’t look at a painting of mine that’s not somehow connected to or influenced by those traditions. You just can’t. Now you may have to look a little harder, ‘cause I’m not giving you any information that’s going to lead you a certain way. My work tells stories, but it doesn’t tell literal narratives.

LPB: There’s certainly a design element going back to West African patterns.

JL: And American culture: Gee’s Bend. I like rhythm in my work. Music and dance. Speed and color. And those are the things that I see that are just as important as what we say or how we act.

LPB: Well, people who act politically, there’s also the issue of, Are you being true to what you’re saying and what you’re doing?

JL: A lot of times they aren’t. That’s why I think Malcolm X was right when he said that you have to think for yourself. The proof is in the pudding. I’m really suspicious of a lot of stuff. As I’ve said before, the work I admire the most is primarily theory-based work, and work that comes from analytical thinking such as Piet Mondrian, John McLaughlin, Josef Albers, Kandinsky, Theo van Doesburg, and Georges Braque. I like to use the mind to get there. I know what I can do. I know what my skills are. But I want to make contributions to a whole cannon of styles, trends, and movements where there’s no black painter to speak of. That doesn’t stop me from admiring the work. I told a reporter once in Memphis, they were talking about how cubism affected Europeans, Picasso and all the great painters. And they asked me what I do in relationship to that. I said, “They looked at African Art and I looked at them.” And that’s pretty much what happened. And a lot of times they had the liberty to get their work out there. But you know, I remember once, David Hammons and I were talking about art or something, and I said, “The wrong people always end up with it.” I was referring to wealthy whites. And he said, “Well, black folks don’t have that kind of money.” And there’s some truth to what he said, but there are some black folks that do have that type of money. So, the issue is, how does one group become sophisticated enough to appreciate a white square on a white ground? And why can’t some people appreciate the same thing coming from a different source that’s just as good? Sometimes it even predates the other thing. It baffles me. What it comes down to is self-determination and free will. When you begin to free the mind, you have these kinds of experiences. I mean it’s no joke. When you determine for yourself how to deconstruct and reconstruct these ideas and theories, you can get to the essence of abstract art.

LPB: You know, a lot of members of my family in Alabama were carpenters, seamstresses, quilt makers… and I remember my father appreciating a well-made thing. And of course that well-made thing was not a figurative drawing, but it was something that he put together with wood. It was something that he labored over. That he formed into something practical, more or less. It’s a deep appreciation for the craft that sits at the base of what you’re saying.

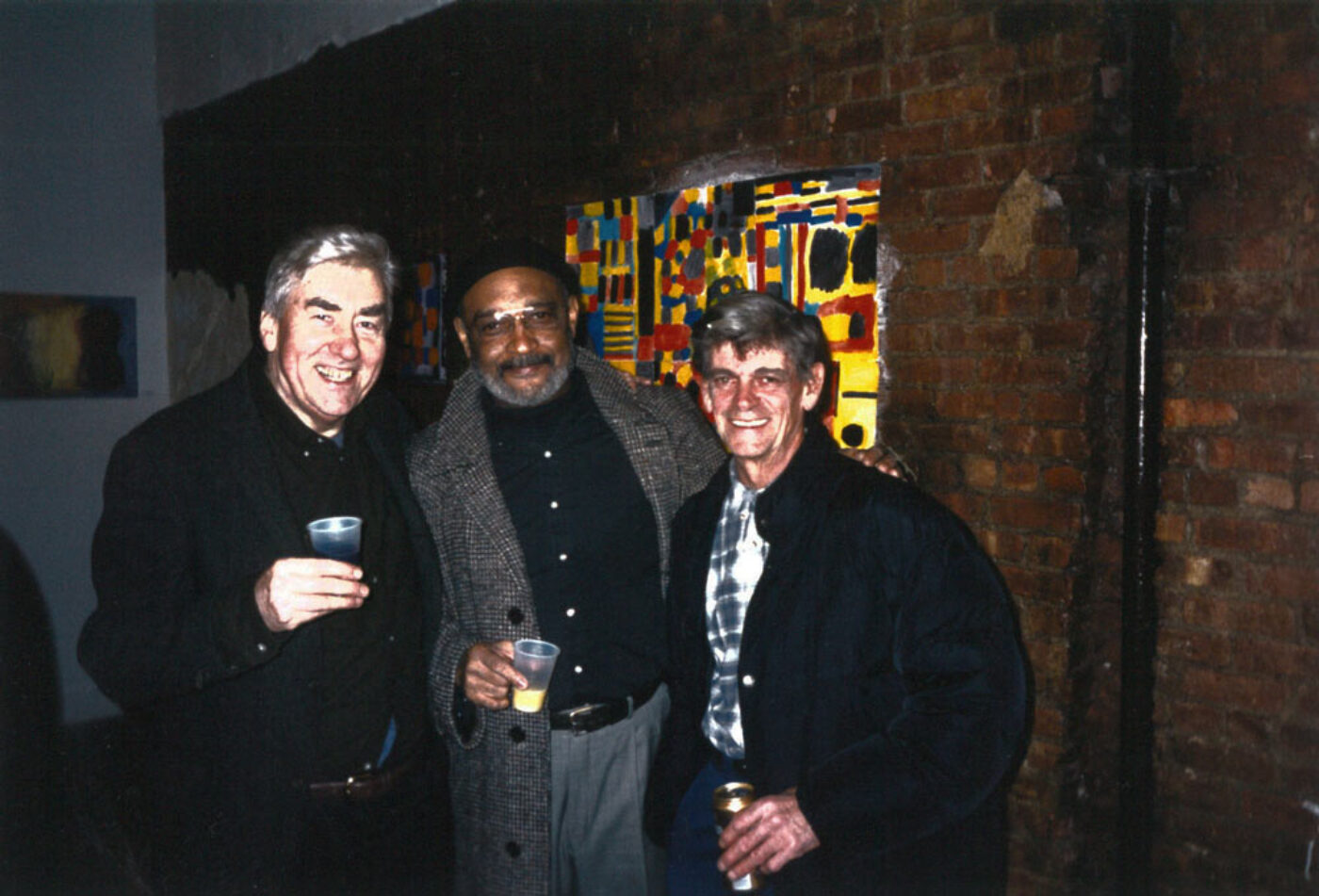

L to R: Al Loving, David Hammons, Fatima Shaik, and James Little, ca. 1984

JL: My mother and her siblings grew up very poor. So, my grandmother used to make their clothes out of almost everything that was available in the house. But she learned how to do these things. She was very efficient. So a lot of that spills over. If I see something that’s not made well. No matter how great they say it is. I’m always looking at how it was put together. A lot of those issues came out with the Abstract Expressionists. Some of it was great work but it wasn’t made well. The ideas were great, but one shouldn’t supersede the other. It has to be a complete synthesis of the two. Good craftsmanship, high skill, is very, very important. And I always try to make art that doesn’t go too far away from that.

That’s why we call it visual art. It’s something that entertains us socially and visually. I try to put things there that you want to look at and want to be a part of. This thing I’m doing for the MTA and LIRR in Queens is all about the environment, and how I want people to feel in the space. How do you want to feel when you’re waiting for the train to come? And who is the space for? It should be interactive.

I’ve been misinterpreted in a lot of ways. But I’ve also been appreciated in a lot of ways. And what I’ve tried to do, basically, is make art for everybody. I really do. I think the reward for me, as far as black folks are concerned, is that if I can excel as a black artist and get to where I want to go, I’m doing good. I’m representing black folks. I’m one of their sons. But aesthetically I’m not going to be pigeonholed. Where I go will not be determined by anybody other than myself. You know, there’ll be some people that appreciate my work, and some that don’t. But I think that if you live long enough, you’ll stick to your guns and put quality first. But we live in a very fleeting society, and a wasteful culture. And people just don’t pay a lot of attention to these things. They like stars. They want their fifteen minutes of fame. But there’s more at stake than just me and my art. You go back to the black community and you say the wrong thing, there’s a price to pay. You don’t want to pay that price because they could draw blood. But, primarily, they just want you to succeed.

LPB: It’s interesting because there’s who you are, and then there’s what you do. And the two need not be intertwined necessarily. So who you are as a citizen, as a person, can be very progressive, but in terms of how that translates into what you do, it doesn’t take away from who you are.

JL: I was in Memphis this past summer. Some folks I’ve known my entire life are still there, and others moved along and did other things. But basically when you look at the big picture, you could just see how difficult it was to grow up there, and then also see how fortunate you are to be where you are now. So when you go back, you can see the importance and the effect that it has on people, in a myriad of ways.

“Lead by example.” That’s what my mother used to always say. “Start doing some of the Lord’s work.” And I said, “I am doing God’s work.” And then she sat there and just looked me straight in the face. She said, “You mean, your painting?” And I said, “Yes, precisely.”

Maasai Re-Construction, 2011, oil and wax on canvas, 72.5 x 95.5 in.

LPB: So you are coming from a theory-based place. And that was very solid in terms of the thinking around the ways in which artists were practicing, especially non-objective artwork. And we live in an era that’s not really theory-based. We don’t really have a lot of theoreticians thinking about art, but you do have trends.

JL: You do have thinkers. But you don’t have theoreticians. You don’t have analytical thinking—very few at least. I was talking to somebody the other day and he asked me if I want to go to a museum lecture. Some of the people that were meant to talk, I knew what they were going to say. And I said, “They can’t teach me anything. I know this stuff. I want them to bring me something that I don’t know. I want to come out smarter than I was when I entered the room.” And that’s not to demerit anybody, but I’ve been to many lectures and sat through the entire thing, and didn’t learn anything.

LPB: Even with the histories of African-American art, you have people like James Porter and Alain LeRoy Locke, who were, in their particular ways, forming theories around what black artists should represent, and what kind of art black artists should be making. Even if you want to compare them to their white counterparts moving up to the 1950s, you have generations of theories that are butting heads. But now you have a lot young artists coming out of MFA programs, who are building a practice that’s about instant fashion or fundamentally connected to the market. I don’t see this kind of deep intergenerational dialogue in terms of how the work is being made.

JL: That’s true. Having artistic skill or artistry doesn’t constitute you being a great artist. It has a lot to do with how you figure out problems. How you resolve aesthetic issues. How you resolve complicated issues, pictorial issues. For instance, look at Duchamp. He started out as a painter and a decent painter at that.

LPB: Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912).

JL: That’s right. He did several paintings. But at the time, he just wasn’t in league with Picasso and those guys. And he knew it. He was brilliant man and he was able to take what he knew and transform that.

LPB: So his strength was his thinking?

JL: That’s exactly right. Mondrian painted flowers in New York to make a living, to pay the bills. But to come up with Neo-Plasticism, that all comes from right here. (points to his head) Breaking it down to a structure, and still making it pictorial, interesting. And you could put it up against anything else.

I got this book by Clement Greenberg, Late Writings edited by Robert C. Morgan. It’s all about advancing the plane, modernism, structure, design, and how all of that overlapped with architecture. That’s the stuff I was taught. I’m very comfortable in those areas. But as you said, these kids today are being taught the wrong stuff. It’s fatal. I was at a talk a few years back, and this young guy, who had gone to art school—I’m not going to say what school, but it’s in Connecticut—said that they didn’t teach him how to paint. He said, “I know all this conceptual art stuff, but that’s not really what I want to do anymore. I really want to paint.” I said well, “You’re getting a late start. I would say go for it. It’s just one of those things where it gets back to feeling. It just can’t be a clinical exercise.” When I paint a painting it’s not just about me, it’s about you. It’s to be shared. It’s community property. That’s when people go around saying so-and-so stole such-and-such. Well, you didn’t steal anything. You put it out there; it’s public property. If you got something you think you could take from my painting, be my guest. But that’s just the way it is. Your soul has to be in it, that’s all. You have to know that this is what you’re going to do, that this is your voice. You have to go from there. And you’re going up against a lot. There’s no cheerleading section till you hit a grand slam, let me tell you.

Maybe I’m just a pessimist looking at the glass half empty rather than hall full. That’s what drives me. I want more in that glass.

LPB: There are some young painters, when they get out of school, who make fashionable work that’s in conversation with contemporary dialogue. But then they may make the choice to sell those paintings very quickly. The stuff they made in graduate school, and the few things they made outside of graduate school… and then they’re often left with the bare bones or nothing in the studio. I’m wondering do you think in terms of the choice of work that a young painter or a young artist should make? I mean how then do they make the turn to say, okay, selling the work is fashionable now. How do they mature after that?

JL: It’s development. You gotta take your time. I was twenty-one years old once. When you’re that young you’re really not that good. I could tell you that much. Every now and then you’ll get a young artist that will shoot through. Those who have that rare talent: Basquiat, Bob Thompson… but I don’t know any of them who lived very long. So you wouldn’t know what they’d be doing today. Was there any room for transition, for development? But young artists today want instant gratification. We live in a consumer culture. If you work with something that has shock value, or some sort of commercial value, I mean you could get it. You could even get on TV. Dancing with stars or whatever… But that doesn’t mean development, that’s not a body of work. That’s not something that’s going to help a large number of people. That’s not something that you could resort back to, and it might be something that you’re not really proud of to begin with. You just don’t know. When you’re that young your work is not mature. All these kids have some talent. If you get in these institutions, when you go to art school, basically we teach pretty much the same stuff… some schools have artists with bigger names, some have lesser-known artists, but that doesn’t determine who’s the best teacher. You could paint a bad painting and write a thirty-page essay on it and have people believing that it’s a great work of art. But you have to be cautious of trends. This stuff changes all the time. I think quality in art is one of the most important things, period. But then the question comes up: What is quality? There was a period where nobody even wanted to mention quality. “That’s subjective.” I don’t think it’s subjective. The story about me in all of this is that I’ve always tried to look at the best, try to find the best art, period. No holds barred. I know a few good painters of my generation, but only a few, at any given time, make it big.

L to R: Stewart Hitch, a friend, James Little, Danny Johnson, Peter Pinchbeck, and Dan Christensen, ca. 2002.

LPB: What are some of the fundamental differences, in terms of your approach to painting, between when you first got out of graduate school and now?

JL: Well, some of the paintings I made in graduate school, the ones that I thought were great, weren’t that good. The most important thing was that I was taking risks and my professors liked that. And I had a pretty good resume going into school at that time—and I was black. And I was smart. All those things were working for me. But when I came to New York it was a bigger stage, and there were a lot of different approaches to art. Some I appreciated and some I didn’t. Some of it I thought was moving too fast, it was too experimental. So I just figured out where I wanted to be. I used to go to experimental music concerts, and performances where people would get naked and roll around on the floor. It just didn’t measure up to the work that was so important to me. I’m a painter.

LPB: So a deep investment in what you’re doing rather than…

JL: I just wanted to improve on things, and continue in the tradition of painting. Not discredit or discard it. I recently was looking at some Latin-American art, something that I hadn’t really looked at over the years. When I first laid eyes on the work, I looked at it with a bias and I shouldn’t have. I was looking at it through a Western lens, from what I learned through school. I thought a lot of these Latin-American artists were just rehashing what Barnett Newman and people like him had done. But then you look at the dates and some of it was done either at the same time or even before. They just didn’t get the recognition. And that’s the dilemma that a lot of black artists have experienced here in the United States. But we can’t continue to sit and complain about those times. And we can’t continue to play the role of a victim. Just get out there and make some kick-ass art and walk away. Let the art do the talking. That’s where I’m at. That’s why my work is not in conversation with the race thing. I like who I am. I’m proud of who I am. I don’t have a problem with the way I look. I like me. And that’s one of the reasons why I like Muhammad Ali so much, because he was like that too. When the conversation is about race I’m just always on the fence because it could go in so many different directions. And the perceptions that people have, you know, the multiple perceptions. You’re as good as you are. There’s always some room for improvement. Sometimes you gotta just look the other way on some of this stuff. I am more powerful now than I would have ever been if I had become say a civil rights spokesman or a minister. And nothing against them, but the reason I say that is because a lot of people are not cut out for that. I’m a civil rights person because of my art.

LPB: So tell me more about your public works project at the Jamaica, Queens train station. Governor Cuomo has to sign off on what you’re doing, right?

JL: Yeah, and he wants to look at some of my designs for other potential projects. The folks at the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) liked what I did. So now, people are taking notice. They want to hear what I got to say. They want to know how I arrived at these things. It just so happens that I’m a New Yorker and I’m a black American.

LPB: There is this conversation between authenticity and affirmation. A lot of people from your generation have experienced the same type of discrimination and segregation that you have. They know what you have been through and can confirm its authenticity. I can understand why you don’t feel the need to transfer that experience into your paintings.

JL: With abstraction you’re coming in with a clean slate. You can’t go looking for anything. I’m not going to give you anything to look for, except some lines, some colors, some designs, and some structure. That’s all I’m going to give you. And the thing about endemic racism when I was growing up—and I told you earlier that my parents kept me and my siblings away from it—we didn’t know about it until we were teens. Restaurants, grocery stores, everything was segregated. When I went to art school that was the first time that I was ever in close contact with white kids. First time! But I never even thought twice about it. I mean because that was the way my mother raised us: to be proud and beautiful, and have self-affirmation and determination. One of the reasons why I have these issues with bringing race into my work, is that when you experience something like that, when you live it, and you see people thirty years later that weren’t even born during the civil rights movement, and they start using that imagery. You could see that it pales in comparison next to the experience. It almost seems superficial to me. I can’t respond to anybody making work about the garbage strike in Memphis [the Memphis Sanitation Strike in 1968], or the riots in Alabama [Birmingham riots of 1963], or the assassination of MLK in 1968—there’s nothing pictorial that can replace that experience. I was right there and it scarred me. But it also energized and reinvigorated me. Dr. King left so much, man. That guy touched everybody in different ways. Malcolm X, too. I’m sort of in between the two of them. I like Malcolm X. I’ve always followed people that stood up for human rights. I like Dr. King’s rationale, his reasoning, and his inspiration. He was so inspirational. That’s the thing I just never gave up on. He also taught me how to survive racism.

LPB: And your ability to translate that in your paintings is an act of freedom.

Near Miss, 2008, oil and wax on canvas, 72.5 x 94 in.

JL: That’s right. I’m rebelling in my own way. It’s my self-determination and free will. That’s pretty much me in a nutshell. And I have a lot of ideas right now. Every time I do something, something else rolls out. I had a little painting I did back in 1999 that did pretty well at an auction recently. It was a white painting. No one ever knew that I did white paintings, but I did. But none of them were racially motivated. These were all formal ideas and theories that I had about cause and effect. I wanted to see how certain things would work in certain contexts. That’s basically what it was. When it comes to this political stuff my mouth is just as big as Al Sharpton’s, but that would never get into my work. It just won’t.

LPB: It’s a dynamic experience. The sort of pandering to popular taste, as an exercise, is something that artists have to decide whether that’s what they want to do in order to be successful.

JL: It’s a tough decision for a lot of artists. I remember somebody was talking about Warhol’s Brillo boxes and how much notoriety he got off of them, and he said, “I wonder what they would have said if a black artist had done that. Probably nothing. They would have just been some Brillo boxes on the ground, and that artist would have taken a beating when he got back to the community.” That’s what I was talking about before. But that’s not the way it works. The structure was in place for him to make it, not anyone else. It was a racist structure. But it still worked for him. I mean it was exclusionary for sure. And he exercised his free will to show and exhibit and put money behind whatever the hell he wanted to. For black artists and black people, it’s always been different. You’ve always had to work harder. You’ve always had to navigate around things to get to exodus. And then you had to protect it when you got there, because they would steal it from you. Look at our music. People just came in and copied the music, took the music from us. So even in the arts you have to protect it because that gets to be the base. Every time someone looks at one of my paintings they try to connect it to a white artist, almost every time. Somewhere down the line they’re puzzled by it. I’ve always tried to do something personal, something that can’t be gotten to unless it comes through me.

LPB: You know, being published in catalogues and having exhibitions are ways of putting your stamp on history, of protecting those ideas. Do you see that or…?

JL: You have to have visibility and documentation of what you’re doing. That’s very important. There’s got to be a record. Once that’s done, it’s done. People can come around and plagiarize, but, as I said before, it’s a reference for anybody. I’ve always tried to be very honest about that. There are certain things that I just firmly believe in. And that’s pretty much what makes me tick. But it’s not just about me.

You asked me earlier who were some of the people who influenced me and my work, and I think I said my father and mother. And then I said Clement Greenberg and George Vander Sluis, but there was another teacher. His name was Dr. Jameson Jones. He was from Mississippi. He studied at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. He got his PhD at Duke University. He taught me philosophy and aesthetics. And he was as good as anybody, apart from Greenberg. Jameson was brilliant, but Greenberg was just the smartest guy in the room. I got ideas from all these people and they’ve stayed in my head. The type of things I could go back to and that give me peace. I try to apply that and teach my kids about having a structure, being organized and determined. But art is something like… I don’t want to call it a drug, but it is. It’s certainly something that I have to do. But what I want is for art to teach people how to see from another perspective. I want you to go home and wonder what the hell this artist was thinking about when he made that picture. “I like it. What’s going on? I want to see it again.” It’s just this whole effort to keep pushing things forward, because I’ve been in New York for a long time and I’ve seen how, when some of us get near scoring a goal, they move the post. I’ve seen it many times. You’re at the top of your game, making fabulous paintings, and next thing you know they’re talking about somebody who blew up some balloons and fill a gallery with ‘em. That’s America.

LPB: So this makes me think of the 1936 Olympics. If Jesse Owens hadn’t jumped from behind the line, visibly behind the line, in the long jump, they would have disqualified him. And he still won the event, even at a disadvantage. And then you mentioned Basquiat. How come he never had a show at the Whitney?

JL: He kept changing the rules. He got more attention than any black artist in history, but he didn’t live long. And he didn’t make a lot of money during his lifetime. And he was so damn young. And he had a drug habit. He gave them what they wanted and they saw something that needed to be exploited. Unfortunately the guy is dead. But you talk about moving the line back for Jesse Owens. Look at what they did to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, when he came up with the slam dunk. They disallowed it. It was called the “Lew Alcindor rule.” They took that out of the college game for a number of years. He was unstoppable. And then they reinserted it later. He came up with the skyhook, too. So that’s the kind of shit that I’m talking about all the time. You gotta keep turning the page. You can’t always have your right hand know what the left is doing. You just can’t. And like I said, you have to protect yourself. You have to protect your art, your creativity, your imagination. I’ve never had that many allies, and my best friends are gone, like Al Loving and Harold Hart. But I have other friends. I knew this painter up in Syracuse, Jack White. And Jack must be eighty now. He taught at Syracuse University. He lives in Texas now. And then I have other friends, some of them are white, like Thornton Willis, and there’s Charles Hinman and a few others. Ed Clark who’s ninety; Bill Hutson, he’s eighty. All these guys are older than me. And I’ve learned a lot from them.

L to R: Peter Pinchbeck, Danny Johnson, and Thornton Willis, ca. 2002.

LPB Ed Clark, Norman Lewis…

JL: I’ll tell you a guy who’s underrated: Samuel Felrath Hines down in DC. He was a good abstract painter who didn’t get very much recognition in his life. Alma Thomas didn’t really get any attention until the ’70s. She died shortly after I came to New York. But she didn’t really start painting until her late ’50s. And it’s just the way it’s been, for whatever reason. Like I said, I’ve never shown in the major museums in Manhattan or Brooklyn. The Museum of Modern Art, Bronx Museum, the Guggenheim, the Whitney Museum—none of them have exhibited my work. So people ask me about that, “Are you in the Modern?” I just say, “Not yet.” They say, “When are they going to do that?” I say, “I don’t know. It’s inevitable.”

LPB: (laughter)