The Texan athlete, who famously raised his fist on the medal stand at the 1968 Olympics, is the subject of a new film premiering this week on Starz.

On October 17, 1968, American track-and-field athlete Tommie Smith won the gold medal for the 200-meter dash at the Olympics in Mexico City. As he took the podium and the National Anthem played, he and his teammate John Carlos raised clenched fists. They were both dressed for protest: each wearing black leather gloves to create a fist representing unity, and black socks and no shoes to symbolize the poverty that African Americans endured. Back then, their raised fists were seen as a symbol of Black Power, aligning them with the Black Panther Party, who to much of the mainstream were a group of dangerous militants. But Smith defined the moment as a symbol of solidarity with the civil rights movement in America. Then and now, Smith says it was a salute to human rights.

While the gesture earned boos in the stadium, this symbol of solidarity helped set a precedent for athletes who had long been taught to keep quiet, and marked a major milestone in athlete activism. Now, sports pros use their platforms for causes, such as Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the National Anthem to protest police brutality, soccer player Megan Rapinoe championing LGBT rights, and LeBron James helping children in need with education. But it all really comes back to Smith.

Smith, who was born in Clarksville, unpacks his loaded gesture in a new documentary that premiered this week on Starz, available on Amazon Prime and Hulu. With Drawn Arms, directed by Glenn Kaino and Afshin Shahidi, starts with the Olympics and the aftermath of Smith's gesture. Fifty years later, we follow Smith throughout the film as he meets Kaepernick and Barack Obama, getting long-overdue acclaim for his activism.

Smith, who is now 76, speaks from his home in Georgia about meeting Obama, sharing his truth, and his houseplants.

Smith and director Glenn Kaino sit before a sculpture that Kaino created in Smith's image, outside the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Starz

Texas Monthly: Nobody really knows that you were born in Clarksville, Texas. Right?

Tommie Smith: Oh, I'm just an old boy from Texas. [Laughs.] I was born there and lived there until I was six and a half. We moved from an old home in Clarksville on a back road, no pavement, all rocks and dirt and trees, to Stratford, California, in 1951, [where] we worked in the cotton fields for the man.

TM: What part of you is typically Texan in your roots?

TS: Hard work. Social deliverance. That was always on my mind.

TM: What did you think when you saw your new film, With Drawn Arms?

TS: It told the real truth. It told the truth that I lived for the first time. I trusted the people who did the video. I smiled and I cried a bit-there were some sad things that happened in the film-but the excitement I had while watching it was that it told the truth about a person telling a story.

TM: How did it feel when everyone was booing at you as you walked off the field?

TS: Sadness. I learned to appreciate negative thoughts. You can learn from anything. As I put my hand up in the air, I saw negative creatures. That's all I saw. Negativity in the air. I might have not seen their faces, but that didn't disturb me. It only gave me the need to continue. When I took my hand down, I said to myself: "Okay Tommie, close the chapter and start another one." That's it.

TM: You had a lot against you, as it shows in the film. When you raised your fist in 1968, you said it was a "human rights salute" more than anything else. Why was this misunderstood at the time? History has changed to accept you now.

TS: It will continue. I call it luck and a blessing. Whatever your belief is of why you're here and how you got here, what will you do? It's up to you. Like the verse in the Bible, "Judge ye not or ye shall be judged." That's what I rely on in my life: Do unto others as I would want others to do unto me. Don't threaten me, because I'm not a threat to anyone.

TM: In one scene in the documentary, we learn that FBI agents followed you into a barber shop, wanting to question you [in conjunction with the 1974 bank robbery and kidnapping of Patty Hearst]. Were you scared at the time?

TS: Yes, it was a thing where I had people around me who didn't know who I was. I was a Black man in a Black neighborhood across the tracks, with two white men accosting a Black business to find a Black man and question him about a white woman named Patty Hearst. This was a time of social change. Dealing with the reality of racism. You couldn't say "systemic racism," we didn't have those words back then. We just had racism. I could see that, but I couldn't verbally announce what it was, but I knew it was there.

TM: At the time, you worked with the Olympic Project for Human Rights. How did this organization help you deliver your message?

TS: It was for human beings, not just for black folks. That was one of my religious beliefs. You must perform the best you possibly can and treat people the best you possibly can. Even the racist attitude of those who are racist, they're doing the best they can at it. I don't believe in killing people. The simplest things are the most difficult to understand. Same as "Love thy neighbor as you love thyself."

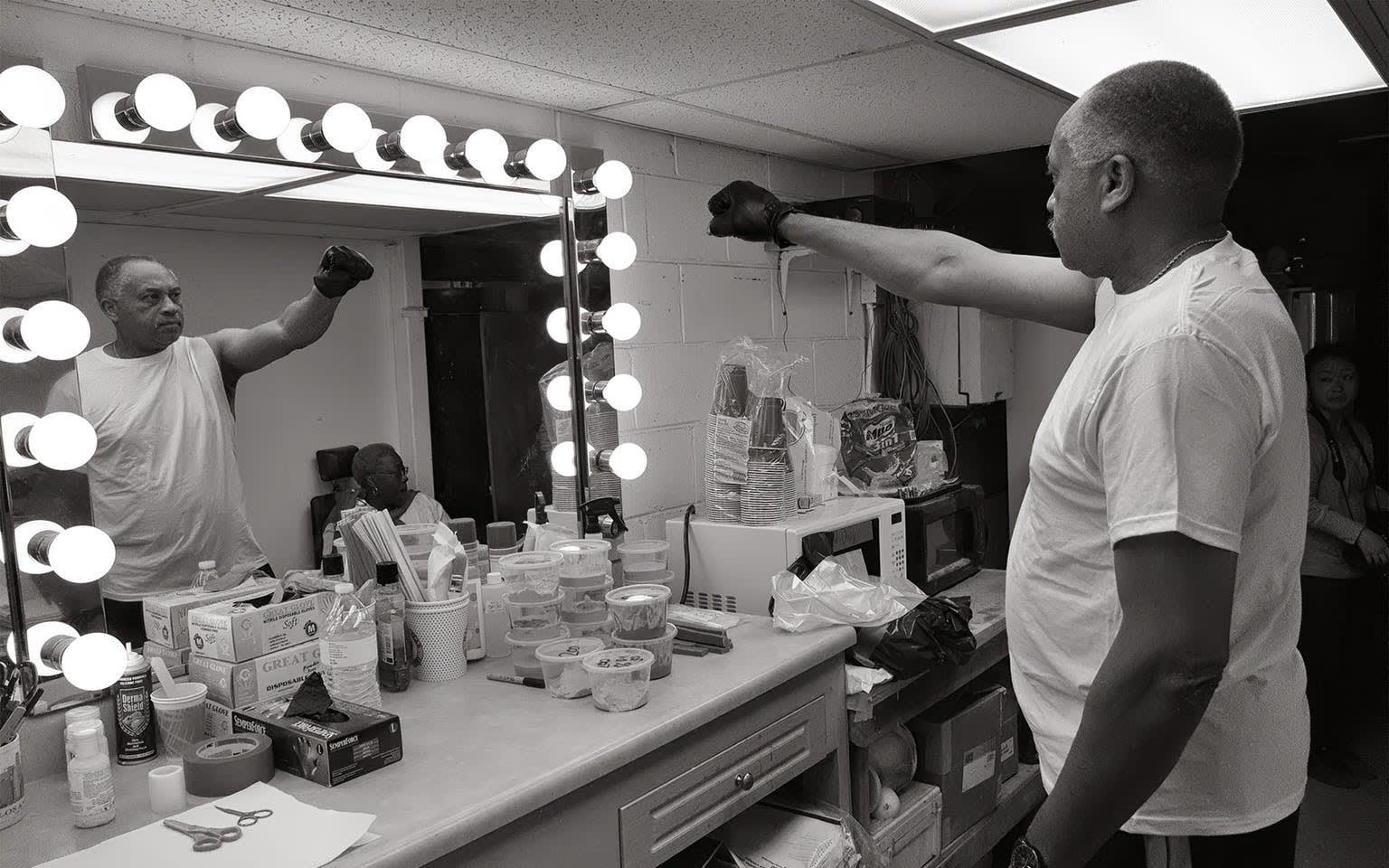

Smith recreates his iconic gesture. STARZ

TM: Has much changed or not changed since 1968?

TS: Fifty-two years of my chronological life. That's about it. Tommie Smith was not a militant, he never will be a militant. I just want people to understand there are other things to think about than vying each other. And moving forward. Conversations through education get past the depiction of stupidity.

TM: In the film, there are young people who say they haven't heard of you until recently, because of Colin Kaepernick's gesture. Do you ever feel erased from history?

TS: There's a lot of people out there who lived the history I lived way back then. That history is not gone, and it will never die. If you look at yourself in the morning and tell yourself, "I am doing the best I can be," you are going to be okay.

TM: In terms of the people you met in the movie, from Barack Obama to Kaepernick, what experience stood out to you the most?

TS: Lonnie Bunch, the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington [who is now the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution]. Because of him, everything I had, the shoes, uniform, anything else he asked for, he pushed the issue for the notoriety and need of respect. I had the motivation to do more than what was necessary. You can't be necessary some days, but all days. Use that reality to plan your life, you can help a lot of folks.

TM: One of the most touching parts in the film is when John Lewis in the film (filmed before he passed away) said you gave him hope.

TS: That's one thing I wanted to see happen. I wanted to hear him speak. He was so endowed with honesty and intuitive love. This was a Christian man who sat in Washington and we talked about the reality of growing up as cotton pickers, that's how we lived. I told him about my parents' backgrounds. I went to school without shoes on. The same thing happened when I went into Barack Obama's office, who is a much younger man, but he understood what I was trying to say. But his attention was on saying: "Your wife is a rose." I wanted to say: "Come on, man! Let's talk about picking some cotton, or something!" Let's break it down to reality.

TM: What do you think about the 2020 election?

TS: The power that is will be a very surmounting fact of what we're going to be living with for the next four years. That's the scary part about it, but that's reality. Whatever it is, we have to live it. Not in the streets killing others. Where I live now, it used to be scary here at Stone Mountain, Georgia, but it's a growing community of people who look to each other and say, "What can I do to help with what you are troubled about?" Then you have a conversation, and that's water in the Sahara. I like it here in Georgia. I got a good wife, a good mother-in-law and a lot of plants.

This interview has been condensed and edited.