Mary Sibande, who is currently displaying her photos at BredaPhoto 2020 photography festival in the Netherlands, speaks with STIR about colour and performance in her work

While you would not be wrong to call her a photographer or sculptor, Mary Sibande's practice is more of a focused insight into the art of weaving a universe around a narrative, with her investigative process manifesting in the form of a visual product. With the tools of textile, space and colour, she writes the stories that her research brings to light.

Using the camera and body casting for ink, the artist writes her world as led by the experiences of her protagonist, the character Sophie. Sophie is made in Sibande's own image, an exploration of the self in wider representation of many. The two of them work with the performative qualities of gesture, placed in interactive juxtaposition with their environment. The artist tells us about her relationship with Sophie, "The character of Sophie is my alter ego, and she plays out the fantasies of the maternal women in my family. I tasked myself with creating this mythical figure that I imagined from stories that my forebearers used to share with me. Their stories were result of the political system of apartheid that determined a particularly impoverished station in life, lives of servitude. Sophie comes as a culmination of their collective escapism; the escapism used in the work to tell stories through sculpture, dress and installation. I cast my face and my body to capture gestures that adorn costumes that are partly maid uniforms, in terms of the blue-coloured fabric that signifies servitude. The form of these garments reference colonial fashionable gowns. Sophie is not a static figure; her story is continuous, she emerges out of apartheid in the blue uniforms, and enters other phases of purple, and currently red".

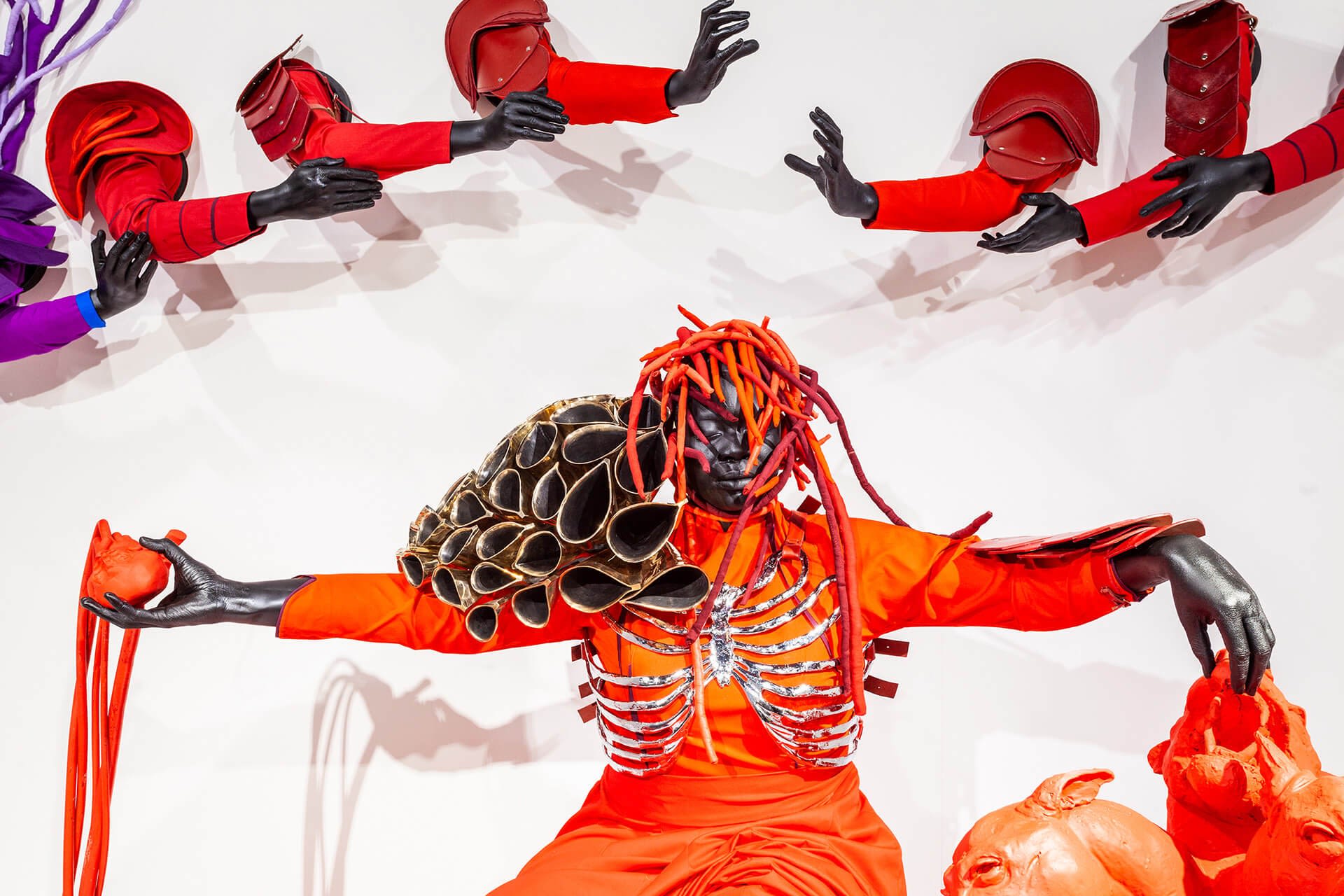

The Domba Dance, 2019 is a sculptural play between colour and visual architecture.

As the artist threads her needle with politics of textile, colour and culture of oppressive culture in a response to Sophie's melting pot of genetic memory and emotional heritage, it is essential to take a closer look at the inherently movement-based nature of Sibande's creative exploration. Although frozen in static image and sculpture, the artist is in continuous dialogue with the experiences her own body holds. In a comment about her role in the process, Sibande says, "I use my body as a canvas by moulding the figures into fibre glass. A similar process to that used to create mannequins. The notion of gesture becomes a communicative device I utilise in the work, I often strive for complex movements. The garments also play a big role in that look and feel of performativity. Beyond the sculptural, also employ my physical body photographically. In this process, I dress up in a garment that I have designed and perform for the camera. I do not regard myself as performance artist, at least not in the traditional sense of performing live in front of an audience. These processes allow me to be explorative about the work".

These processes also shift my interest from the visual product of her research to the process of her grappling with her form-based choreography. While her work stands out to the eyes immediately with its perfect placement at the crossroads of visual architecture and articulated narrative, as a viewer I tend to anticipate the opportunity to see more process oriented, performative aspects of the journey to developing her own universe.

The Domba Dance (2019) features Sophie, Sibande's protagonist / alter egoImage: Mary Sibande and Kavi Gupta

Sibande talks to us about her negotiation with systems of hierarchy and generations of conflict through conversation between textile and colour, “The often-voluminous textiles I use have symbolic value, particularly to a South African audience. They determine class, and work similarly in identifying where human beings lie on the social strata. I was drawn to the various blues of my first body of work, the exhibition Long Live the Dead Queen (2009), because of their links to identifying the working class in my country. Because of my social standing, as the first woman in my lineage to have access to tertiary education, I am equipped with the voice and the means to express myself. The character Sophie Ntombikayise wears a purple gown. The symbology leads back to how purple was the colour of the clergy or wealthy in Europe. Furthermore, purple became the colour of uprising and protest. In the dying years of apartheid in South Africa, a march held in Cape Town was dubbed the ‘Purple Shall Govern’. The name stemmed from two references, the first from the Freedom Charter promises, and the second reference was born out of the protesters being stained with purple dye from police canon, so that they may be marked for later arrest. The underlying ideology here is that colour of a person’s skin and colour of clothes that they wear are also markers”.

They Don’t Make Them Like They Used To (2008) by SibandeImage: Mary Sibande and Kavi Gupta

Sibande continues, “The red phase for Sophie began with an idiom about anger, the protesting black figure did not disappear with apartheid, but kept in a rainbow nation lull of Nelson Mandela’s presidency. The angry protester who is disenfranchised in democratic South Africa has been awakened by the continuation of the status quo… There is an isiZulu idiom that defines anger as a form of animalism. The hue that defines this is red”.

I'm A Lady (2009) by Mary SibandeImage: Mary Sibande and Kavi Gupta

Sibande’s work is currently on display at the BredaPhoto 2020, a biannual festival in the town of Breda, Netherlands. Her work is on view at the festival until October 25, 2020 (schedule may be disrupted due to the ongoing pandemic).

A portrait of the artist (2020)Image: Mary Sibande and Kavi Gupta