Michael Joo is an artist whose multivalent practice encompasses sculpture, painting, printmaking, photography, installation, video, and performance. Along with Do Ho Suh, he represented South Korea at the 2001 Venice Biennale, and was included in the 2000 Whitney Biennial. His installation at the National Museum of Asian Art, called Perspectives: Michael Joo, was on display from July 2016 to July 2017, and he participated in 2013’s Come Together: Surviving Sandy, curated by the Rail’s Phong H. Bui. While Michael’s work has been described as “cyclical,” he himself calls it a “cumulative practice,” something that generates new ideas and exploration for himself and his viewers. That exploration includes such moments as being licked by an elk (what he describes as a “muscle” coming into contact with his body), scouring the streets outside New York’s bodegas to find plastic bags to blow up, or playing games with the children of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea. Throughout, he is seeking to pose questions rather than find answers, even as he invokes the scientific method. When we spoke in preparation for this conversation, Michael told me that, “to empathize with a rock is very difficult.” That is true, but it is perhaps one of the things that his art tries to help us with.

Amanda Gluibizzi (Rail): You frequently describe your work as occupying a liminal space. And it certainly does seem like we are in one currently, not least because we don’t have a lot of options for ourselves; we’re kind of in a weird sort of holding pattern.

Michael Joo: One thing that’s been drawing me to those spaces is that they’re undefined, and very often constructs. And sometimes those constructs, if you look deep into them, you might notice clues to the identities of other kinds of spaces that have been generated by the very fact of this construct. So even though this is a construct made by people that physically doesn’t exist, perhaps, it becomes real, and the kind of reality that forms around it is undeniable. I think that might be an appropriate way to describe the liminality of now. The very real urgency that’s been snowballing, and building up at the edges of this unacknowledged space of social disparities, this inter-in-between space, is finally getting some expression.

Rail: One of the things that struck me as a through line in your work is an interest in indexicality, something that is invested in a presence; it ties both your early work to your later pieces, and also the work that you make that is more abstract with those that are more representational. Could you speak to that a little bit?

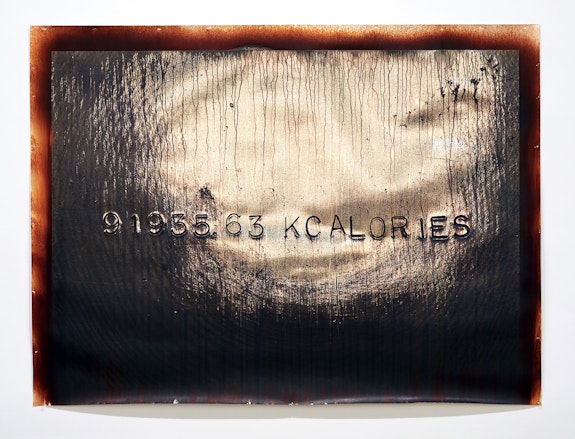

Joo: I think that indexicality is important in my work. Relinquished (2018–19) records a practice of calculating calories, of presence. This image’s indexicality was generated by metal stamping into aluminum and photographing it, printing the image onto paper in a transparent ink, and then literally developing it in space as a reference back to photography, a medium with a definitive role in indexicality. And in this case, the presence indicated is the number of calories that you could consume if you ate an entire human body. So, this is the number of calories of energy the body has to offer. It has a sister piece, which is called Acquired (2018–19), which is the number of calories per second that it takes for the body to consume itself, based upon the physiology of the Buddha when he was moving toward enlightenment and fasting ascetically, as paired with real data from sports medicine and polar exploration and the body’s own consumption of itself. These things are factually and attentively researched, but ultimately, there’s a leap, and the proof is yet to exist, the indexical only signaling its presence. For me, the substitute for proof might be indexical “evidence” in the work that follows the parameters of a scientific methodology, and even jumping medium, whether more closely focused on numbers and objects or zoomed out to index larger systems, abstract or representational. By using multimedia, by jumping from one stream to another, this proof or record doesn’t have to be limited. And so the proof of image resulting from the chemical reaction of the silver on the surface of a work, results in a numerical figure that refers back to this kind of impossible proposition of calculation and presence combined, and is where some of my work sits, it’s at the core of a lot of it.

Rail: Even in your early video Salt Transfer Cycle (1993–15), where you’re dealing with huge piles of MSG, where you’re licking salt, where you yourself serve as a salt lick, there is this way of thinking about mark-making that releases the artist, necessarily, from a certain amount of decision making where the hand is present.

Joo: It’s great what you said about marking the body; I feel like I haven’t really pursued or thought of that enough. But the relinquishing of the hand is something that I was very interested in in this work, which was a three-part video work in which I wanted to move a character, myself as a fictional character, from east to west by going west. I chose three sites, among many, along this route to film at, the first being a shoot in my studio, at the time in Chinatown, where I swam in a performative work through 2,000 pounds of MSG that we had dumped into the studio in a large toxic lake. In the next piece, I was transported to Utah, the Bonneville Salt Flats, right on the GPS coordinates of a track, where they would run the record speed cars, and all this linear effort would go for naught as something that was meant to be surpassed and beaten again, and enacted a parody of evolution. And then finally, in this odd kind of cycling, interrupted patterning, ending up covered in salt, as a result of all of this energy expenditure, and sat as this kind of quasi-Butoh salt lick, waiting for 10 days for elk to come and ingest the idea that I started with into the reality of their bloodstreams. So, the concept or conceit was, how do we transport an idea into reality, into hyperreality, and so on.

Sitting on the side of the mountain, the scale of the elk was incredible; they are so visceral. Anything that I’m talking about may sound lofty and ethereal, but the fact of sitting alone, covered in nothing but malt syrup and salt, and after five days of delirium, running out of food and water, triggering remote cameras, only aware that someone’s changing the cameras—hopeful that somebody’s changing the batteries in the cameras—and feeling very vulnerable when this giant muscle finally comes and touches the skin, licking away salt and syrup as well as the red ants that were swarming all over my body at that time. There was nothing like that to realize you are; that you are where you are.

Rail: You have the bites from the red ants, but you also have of course tiny little cuts from swimming through the MSG and then also as you lick through the salt flats, your tongue is being worn away by this material that’s exceptionally rough even though it looks so beautifully smooth. Here is another way that we can start to think about indexicality and the way that that works in your practice. You spoke to me quite a bit about scar tissue, and the way that accident or action can leave its own mark on your body, and there too, the scar tissue is this index of your practice.

Joo: I think that’s what’s interesting to me, the physical evidence, and maybe there’s something of that in sculpture, and my interest in the idea of manifesting artworks at the point they might be viewable. This practice could go on and on and on as pure process in many ways, but there are always moments where there is evidence. And that evidence or scar doesn’t have to be an end to itself. Everything’s changed by it and the rest around it recalibrated, as a scar to the rest of my own body.

Rail: Could you talk a little bit about the scientific method and how you might think through that analogy to your practice? For example, how do you know which idea you want to pursue through all of these things that are swirling around through your process?

Joo: Well the language I use comes from where I was formally trained, and the environment I grew up in, which was the lab. Both my parents were scientists, but they diverted in their pathways, my mother more towards plant physiology and food security and my father went off to animal breeding, both with the ideal of reconstructive efforts for post-war Korea. I grew up inside their laboratories, but always there was a kind of—not utilitarian, but kind of idealistic end to the pursuit of that science, which was feeding people. There was always kind of a function as well. One of the things I ended up in early on, before art, was very low-level work with a seed science company.

It’s really the part of scientific research that is the asking of a question; that’s where the work will start and what interests me. And sometimes the question will take the form of an impossible image, you know. Sometimes it tends to be within a structure, or even within something I see in a pattern. Like the idea of a liminal space between patterns that is also their backdrop. I think it’s something I wasn’t aware of when I was doing it in the past. But over the years it becomes more evident in the course of one’s body of work. What I do know is the method and the methodology, just how the process will begin, and the habitual kind of enactment of that process which involves rigor and skepticism about outcomes. I’m interested in potential and possibilities and that’s where things diverge from conclusions, and maybe that’s where it becomes non-functional, not useful as we understand it, like a statement, but also perhaps not prescribed, or predictable, and that’s not something that’s favored by the scientific method. There’s a lack of prediction or conclusion….

Rail: You said something that struck me about this pursuit of an impossible image, or the impossible image that happens to your mind as you’re thinking through your ideas and starting to begin a piece and seeing it through. What do you do when you hit an impossible image?

Joo: [Laughs] I think when I hit an impossible image, I find an analog, and one that’s not a compromise. For instance, in Bodhi Obfuscatus (Space Baby) (2005), I was given permission to work with the Rockefeller collection in the Asia Society. In this intervention with their collection, I saw these beautiful, amazing holdings that were collected and put away and they weren’t on view. I wanted to get us a little closer to them as objects and also close to this particular figure, which was a Gandharan Buddha from the second century, which to me seemed very influenced by Western sculpture. I thought one way we could get close viscerally would be to allow crickets or insects to crawl all over its face. Even the thought of that in pre-production meetings sent out alarm bells throughout the museum, so that image I had of a single insect crawling across the face of this sculpture, within the institution, was an impossible image. Ultimately, the resulting question became, what would the insect’s eye see; how does it see? And how would that look? It was a shift in perspective. It wasn’t a logical jump, but the solution for me in rerouting was to point the eyes as cameras on the face, 50 of them, that see at the same time, and allow us to see at the same time. Maybe not necessarily like an insect, but the pathway was a series of analogs through that original idea. In a sense, this fractured image was for me a more satisfactory and expansive solution because the surrounding 100 mirrors and monitors fragmented the face as well as the viewer and brought us all together in its circular ring outside the figure in service of looking more closely at the center.

Rail: It's a wonderful installation as well not just because of the close-ups that we're able to see on the screens—which permit us to get up close to the face of the sculpture, which is so exceptionally important and yet something that we're generally not allowed to do. Because of course, so often, artworks are positioned slightly above us so that we can't touch them. But also, this veil that surrounds the Buddha's head causes us to attempt to look at it more closely. We’re attempting to see through this armature into this thing that is the real thing.

Joo: This veil was like a space helmet to me. It was done with the help and advice of the Buckminster Fuller Institute at the time over in … I think it was in Williamsburg. And that led to a discussion with the people who work there, and even some direct collaborators of Buckminster Fuller. It’s interesting that this veil, so to speak, is a very dense veil, but visually, it's very light. The Asia Society was so great about letting this hover over it; really carefully getting this piece to float over the sculpture itself was a big deal for me.

Rail: And how did you want the viewer to experience this piece? Did you want people to walk around? Did you want them to stand in front of the piece and attempt to engage with the sculpture itself? What was your hope for the piece?

Joo: It’s a really theatrical piece. I think for me, it was unusually theatrical. There’s an artifice… I wanted there to be something that you’d have to process. As one’s eyes adjusted to the light, I wanted that whole image to be absorbed at once. There was a center. The center point was more lit, so I hoped only that something was recognized. And that recognition brings you, if not physically closer, at least makes you look around it. And hopefully what you see points back in a contextual way to forming clues to what that is or how it’s built or why it is. Hopefully, what you take away is your own reconstruction of the piece and then face through the darkness or how you were implicated in that. But it’s not meant to be seen in any kind of prescriptive way.

Rail: One of our participants just put a question in the chat: “Was the work silent?”

Joo: Yes, it was. That’s a great question. It was very silent, and we had this carpeting and everything to deaden the sound as well.

Rail: Oh, that’s interesting, wow.

Joo: It really absorbed, and everything was painted black, so again, very theatrical. The effect was to get you to focus on yourself, your own presence when you’re in the space.

Rail: And I assume that the carpeting helped to not just dampen the sound of footsteps, but to dampen the footsteps themselves, too. I’m assuming that the halo didn’t shake very much, or did it?

Joo: No, it didn’t at all. It was absolutely shock-absorbed and isolated [laughs]. But what was great is that your very footstep was kind of muffled, so the way your body records the way you move through that space was muffled and distanced. I think that has a lot to do with hapticality and a lot about touch, intimacy, and how we gauge our presence about where we are and locate ourselves, and that’s changed right now, especially in this current pandemic context.

Rail: You mentioned to me yesterday that a material approach can be a way of growing knowledge, which is a way of thinking about science, of course, but also about artwork, this idea of expanding our minds and allowing us to acquire knowledge of things. Could you tell us a little bit about your material decision-making?

Joo: DRWN, Carunculatus (28) (2015), for example, is based upon research again and in visiting liminal spaces. I’ve long been interested in birds and bird migration, and one of the things that I was looking at was the imagery of the cranes that I had grown up with, which were traditional symbols in Korea but also contemporary symbols of conservation, and of threats of species extinction. In that work, graphite and urethane were used to cast threatened crane species’ legs and feet. I was inspired by photogrammetry I had been doing of specimen samples collected by British colonial explorers in Korea from the region, pre-DMZ, that are in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian. And this particular species [of crane] is seriously endangered. The casts, every time they’re installed, leave a graphite mark and a portion of themselves behind. So in a way, there is a process, just by the act of installation, of mimicking what’s happening: the destruction of the piece itself, very slowly and subtly, almost elegantly. It’s really based on looking at the material for parallels in the systems that surround it. But what I extrapolate from this continued investigation, and interest in migration and movement in specific liminal spaces, is applicable to others.

In Locale Inscribed (Walking in the desert with Eisa towards the sun, looking down) (2014–15), pursuing that path of the idea of movement; I was looking at the movement of water through desert systems and the migration of people, looking at all these present and ancient irrigation systems in the United Arab Emirates near Sharjah that are in use or being excavated from the desert and which are one reason for nomadic movement and migrations. Even as the water went away and then left a place over time, [other] water was brought in, supporting and drawing people and the fact of this then drying up, leading to further migration. I mapped some of these irrigation systems, the ancient ones merged with the recent local ones, as the basis of an intervention in a Sharjah port warehouse where migrant workers worked and squatted, first excavating them in the floor and revealing the building’s foundations, which pointed back to the hands that made them. And then silver-nitrate mirrored the largest end wall of the site’s interior, which revealed the traces of the hands that made it, and when combined with all the light from the space, amplified both the presence of place and also the viewer’s. Aside from traces and presence, there is something in this example of material investigation through silvering that also asks “why photography” for me or “why an image?” By basing it in a very foundational laboratory experiment, and merging it with processes learned from glassmakers in Venice, of mirroring glass, and further overlaying these processes onto silver gelatin printing techniques, the results approach, in a perhaps in a somewhat roundabout way, a kind of image-making practice to me. Or image-referential, practice–indexical, I guess.

Rail: This is a piece that I’ve only ever seen in reproduction. I’m curious about it: Were people allowed to walk through the exhibition?

Joo: Yes, they were allowed to walk through it, and it was open all night, lit by mercury-halide lights that made it a really eerie oasis of sorts; we allowed, with some difficulty, people to continue to occupy the space and the upper floors who were working there. So, it did have a kind of itinerant population, daytime usually, some nights. It was occupiable space.

Rail: It's important to think about not just being able to inhabit the space and the way that we talk about that as art people, but that people inhabited the space.

Joo: It was a semi-used but privately-owned warehouse, and as it was being squatted and fell out of use, it was later destroyed. A couple of years later I got an image from some students in the region, and it was channels and debris; it had been reabsorbed by the site, so now it’s this kind of flat place with fossilized traces—with evidence, rather, of this excavated drawing.

Rail: So much of your practice is either meant to be installed in a particular place, or it's drawn from a particular place and the evocations that that place provides for you and you're hoping to provide for your viewer. I think we could understand it as being multi-focal: we could understand site-specificity as migration, as movement, two of your words that you wrote to me this morning. And even a moment in time, if we think about temporality as site-specific work. So, we could think about your work at Sharjah, or the DMZ, or fossils as being site specific.

Joo: Yeah, absolutely. That's a great lead in from you to Saltation, Traction, Precipitate (2018). In it is a bridge called the Friendship Bridge, which I believe was initiated by North Koreans, before the Korean War, at a time when the border was at a different place, and which was then completed by the US Army Corps of Engineers as the movement of borders and occupied territory continued to shift. It is a very particular architecture and vision of a specific perspective in the form of a regime, of another government. The bridge next to it was built because the original is deemed unsafe and is the new Friendship Bridge, which is actually usable. A third bridge flanks the new one as an upgrade to the current functioning one, but not yet in use. The historical versions of this bridge, crossing the Han River, are on record at the same time, but also displaying the different shifts in priorities and ideologies. What’s further important to me is this is also where my mother crossed over on her uncle’s shoulders from North to South Korea in the late ’40s. So, at this point on the river, the context was incredibly charged for me for personal reasons, as well as those we’ve talked about. The scar tissue and liminality as the analogs for the social ecologies that develop around living in such contested and shifting places. Maybe even the animals have a particular kind of identity and role, from symbolic to scientific. In a way the people that exist there and the social lives that they lead are very real new histories. And I think they will teach us something.

In my desire to study this, I worked with a number of school kids in the region who live in communities around the DMZ to collect rocks, which are one of a few geologic things, that can move perceptibly in our own lifetime—through saltation as pebbles move down a river system. The Han goes up and down and every way but north and south, even as it crosses from North to South. At this winding point in the river, we explored the bridges and collected rock samples, that were used in playing a children’s game called “tangt-tah-mok-ki” which is basically a territorial game. They’ll throw a rock and create a geometric pattern and the one with the biggest domain wins; the goal is to eat and consume the other territories. I had the kids play this game with these volcanic rocks on the original Friendship Bridge and then again in a place they can’t normally access, the Cheorwon Peace Plaza which is about 100 yards from the DMZ within the military-occupied zone. On that plaza I had the children play the game and recorded their pathways in the much larger territories that they were making. We then took the samples of the rocks, collected and scanned them, and we composited them into a large-scale, cement-cast version of this single rock that we then put in the site at the Peace Plaza, which is a plaza for the future, really; it’s a public plaza that it is not public yet. So, though my interests don’t usually tend towards monuments, here was a monument that wasn’t about the past but a monument that was yet in formation and had no clear identity. And I felt that was a good analog to looking at the deep past in a way, rocks and pebbles that might have come from an unknown volcano in the north that flowed down to the south. These are the kind of discussions that I had with the children, for them to talk with their parents about and to use as a hub for talking about the reality that is beyond reach as well, which is their grandparents' movement down through that system.

Rail: It’s really beautiful.

Joo: About 100 yards away are thousands of mines and the world's most heavily guarded ecological preserve. After thinking of all of these places that were so external, and that were so site dependent, I returned recently to thinking about the body and with the “Single Breath Transfer” series thinking about the site that we occupy here, in how things are transferred and transmitted. One of the things we talked about was knowledge: I'm very interested in how something is passed on to another and particularly with regards to being an artist who sometimes works with fabricators. In this case, I collected bags from the street to inflate with my own breath. I was considering some digital thermal imagery of the lungs undergoing a test called the single-breath transfer test, which is a measurement of the body's ability to absorb toxins in the air, and that single breath transfer test, which is taking a breath of carbon monoxide, and exhaling to deduce what’s absorbed, is the reference point of this piece… With my own leap being to manifest how that would be transferred. I collected bags from outside bodegas and on the streets of New York, and would inflate them to the limit of my own breath, my own single breath, and next froze them with liquid nitrogen or CO2 and then wax to arrest the form, and then quickly molded this in investment and passed it on to the glassblower who then put his or her breath into the molten glass which expanded and burned out the bag inside of the ceramic mold. The resulting mold-blown glass form is a record or metric, like a gauge. I wanted to make vessels that are records of that transfer of breath. In a sense, the glass, a frozen state of this liquid material, given the conditions of our world, is also a record of transmission or maybe the passing on of something to another, one person to another one human.

Rail: These are fascinating to me; I have so many weird, nitpicky questions about them, like, did you clean the bags first?

Joo: Recently, more so than in the past, yes. A little reckless, perhaps.

Rail: Glass blowing is an intensely physical process; glassblowers are very much akin to athletes or to singers, where they have great control over their breath. This too, was a question that I had for you: how do you feel like your breath compared to the breath of the glassblowers you were collaborating with?

Joo: That’s a great question because it's obviously nothing compared to their abilities. You know, one of the glass blowers I work with could probably blow up an industrial drum with one breath. I could barely blow up some of these bags. But I felt it was appropriate, because it was the scaling down of material, the humbling of a big idea into plain and then not-so-plain material. What the material's asking of you is also something I'm responsive to and aware of. Sometimes I ask questions of the material in order to push it. But that acknowledgement of control is as close to research as it gets, and as close to science, because I think what I'm really listening for is how it's pushing back in that process, finding out where we might go with it that's not been yet explored, and what it might mean to us because it does.

Rail: Some of them possess color. Is this found color? Or is this a decision that you are making?

Joo: It’s a decision that began based on the colors of the original bags themselves, and done with what's called the Swedish overlay, a very tricky process. One of the fellows at Wheaton Arts assists in making these and showed us this technique of literally embedding a bar of colored glass into the molten ball and really impregnating the color into the glass, as opposed to pigmenting, and in effect blowing through the merged glass so the color when blown is extruded and fused into the glass itself as it stretches to form. It might sound a little too grand the way I'm describing it, but it's a really quite amazing.

Rail: They’re stunning. I love the installation shot, too. It must have been remarkable to walk among them.

Joo: Maybe I’ll close with some work I'd been doing with trying to bring fossils sections together through imagining and mapping uncontestable landscapes and 500-million-year-old real estate, and seeing if I could bring some of these fragments back together again into something we could actually touch, a space we could experience, that would aspire to bringing us closer to what we can't comprehend or really process or empathize with. And working with these distant and inaccessible objects has led me more recently into working with 3D digital scans accessed through the Smithsonian Open Access program, which has been offering unrestricted public access to the 3D scanned image files of their vast archives. Within the archives of the National Museum of American History, I was drawn to the life cast of Anne Sullivan, Helen Keller's teacher. This life cast bust, which is really different from a death mask, was fascinating to me, because in it was the physical record or topographic map of the vibration points, the movement, and texture of Keller’s teacher’s face, through which she was able to receive and construct, or generate language and voice of her own. The haptic moment contact referenced in it. But we still don't know exactly what happens when touch is received and then processed by us, and what human triggers result. There is something in there about art for me. Something very particular that goes on; it's pretty incredible, the leap that's made. Since a digital 3D print can't be built without being based upon and anchored to the ground on which it’s built, I have been using these structural support points as key corollary analogs to the points of Keller’s touch on Sullivan's face. An architectural model and topographic record of another type of transfer. As a teacher and as a parent, I think this transmission and resulting knowledge generated has more positive resonances than the kinds of transmission we're looking at right now.