Helping museums acquire work by underrepresented artists has been the goal of the Atlanta-based Souls Grown Deep Foundation for the past two years. In 2018, it shifted from loaning items from its huge collection of Southern, African American artists to placing them in museums' permanently.

"Loans are wonderful, and they have an impact in the function of exhibitions and displays," says the foundation's president, Maxwell Anderson. "But they don't accomplish the larger objective, which is to see the works in the permanent collection alongside other works of 20th century American art."

The foundation's collection is "so massive" they could have opened their own museum, says Franklin Sirmans, director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, who joined the Souls Grown Deep board last year.

"That would have been nice and some of us would have made the pilgrimage. It would have never, never had the impact that I believe they're having now," Sirmans says.

Souls Grown Deep has placed 400 pieces by artists including Thornton Dial and Nellie Mae Rowe permanently in 20 museums including New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

The foundation sells the work to museums at below-market prices. Which is a good thing, because nowadays these works have become costly as museums are scrambling for artists they ignored during their lifetimes says Valerie Cassel Oliver, curator at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

"The desire is to have them, but they're now too expensive and it's like, well, yeah, there were certain works that were $2,000 in 1970 when you didn't want them. Now they're $200,000," says Cassel Oliver.

So, to afford them, some museums are selling other art. Two years ago, the Baltimore Museum of Art decided to sell paintings to raise money for more work by women and artists of color.

Christopher Bedford, Director of the BMA, says the museum sold seven paintings, "all by white male artists which quite naturally represent the redundancy within a collection due to a history of both conscious and unconscious bias."

The sale of works by artists including Andy Warhol, who Bedford says are still well-represented in the museum, raised $7 million – some controversy – but also praise.

Last year, SFMOMA sold a Rothko it had in storage. The Art Gallery of Ontario sold 20 paintings by a Canadian landscape artist to purchase more indigenous works.

But Cassel Oliver says she's not crazy about these types of sales.

"I think that sets up binaries that I think feed into this notion or this anxiety and this fear that in order to represent other people, you have to erase or remove others. And that's a fallacy," asserts Cassel Oliver.

She says if museums really want to expand their collections, they need to make it a priority to raise funds from donors "to buy works by women artists ... to buy works by other artists of color."

More museums have been setting up targeted funds in recent years, and that's important because it sets goals to last. Museum leadership can change. Momentum can fade. The terms of the donations remain in place.

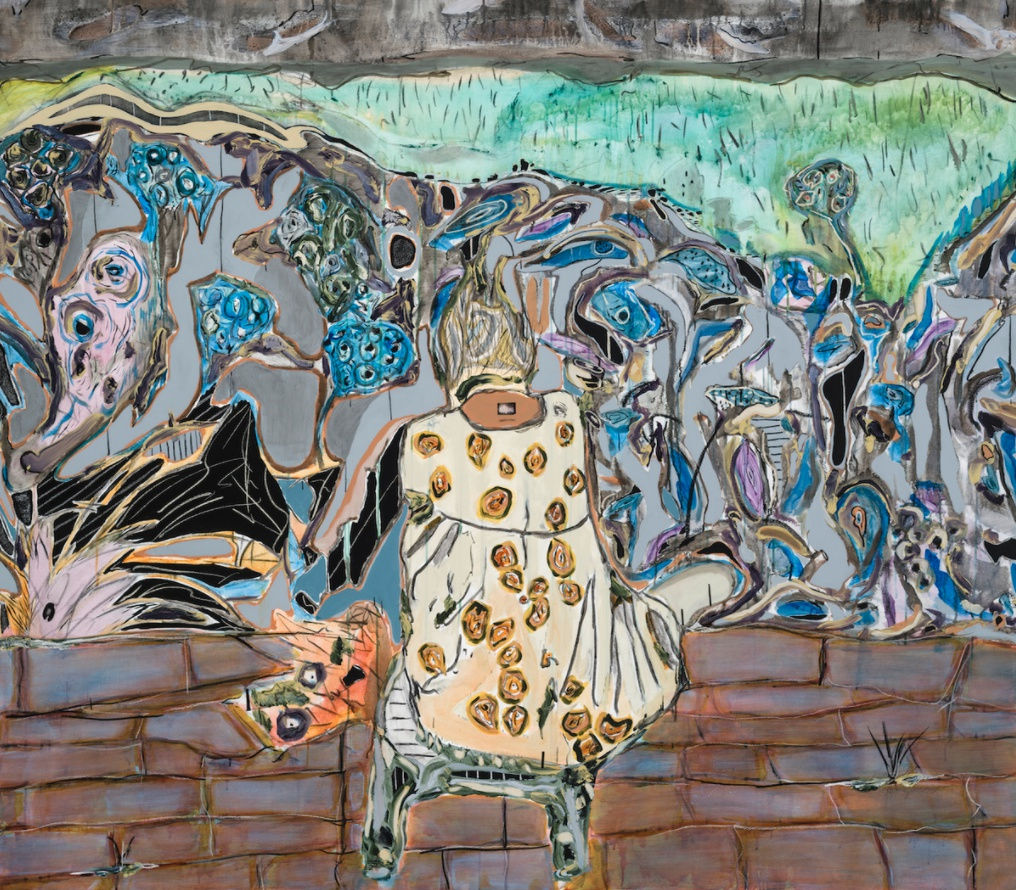

Artist Manuel Mathieu thinks his grandmother would be more pleased with the fund that bears her name than she would seeing Self-portrait on the museum's walls.

"She did make a difference in my life. And I think it makes sense that she keeps making difference in other people's lives."