The Washington, D.C. Commission on Arts and Humanities just seriously upped their game with their latest city-wide temporary public art project called 5 x 5. Five curators brought 25 artists’ site-specific installations to all 8 wards. Each piece we toured highlights an aspect of the District’s changing identity in the face of rampant redevelopment and gentrification. Many pieces make a combative, political point, wading into some of the most troubling issues in the city, while others offered more nuanced stories, but still aim to strike a chord.

Underlying all of it was a genuine effort to bring compelling pieces to all D.C. residents. As Sarah Massey, who was doing outreach for the commission, explained, “this whole project is a dialogue between the monumental core of the city — where all the tourists go — and the actual district, where people live. Do people who live in Anacostia go to the monumental core? We don’t know. The commission wanted to bring art to where people live.”

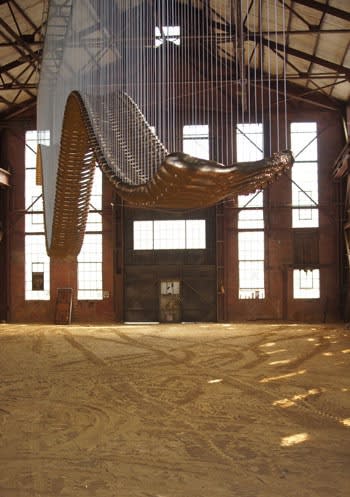

We start at the Navy Yard, which has gone from being the site of abandoned armaments factories and strip clubs to one for high-end condos, restaurants, and a hipster-loving trapeze school in less than a decade. Many of the old naval buildings have been taken over by new restaurants, but one that has yet to be turned, a gorgeous empty shell of a building, is now the temporary home of Glenn Kaino’s magnificent Bridge (see image above). Kaino’s work overwhelms on first sight, appearing to be a hundred-foot-long dinosaur spine hanging from the ceiling. But it’s actually a bridge, made up of 200 unique slats. Each slat is a cast of athlete Tommie Smith’s arm, with a clenched fist at the end. Smith made his famous Black Power fist at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, where he won a gold medal. For this political act, Smith was expelled from the games.

Kaino writes that the use of extended arm and fist was long a political symbol before it was appropriated by Black Power activists, and its meaning has since evolved, given our ever-shifting understanding. The bridge is then meant to show this path of a “revised, formed, and remitted cultural narrative.” Smith seems to reflect that changing narrative himself. When I asked him what the Kaino’s piece said about black power in the District today, he replied, “Well, I didn’t actually make the Black Power sign. I was showing solidarity with all the world’s repressed people. It was a sign of freedom.”

As we move to Anacostia, we learn about a series of billboards that match African American male poets and visual artists to create site-specific billboards around the city called Ceremonies of Dark Men. As curator A.M. Weaver explains, “D.C. used to be the Chocolate City, but it isn’t anymore. We need a new way of looking at the black male figure. We want to re-assert this figure in a changing community, with all the hipsters coming in.” Weaver picked highly visible spots in every quadrant and augmented the billboards with apps that have video slideshows. She said each juxtaposition between image and text was carefully curated.

Heading towards the Southwest Waterfront Metro stop, we are confronted with a group of five pieces in what was empty grassy space next to a D.C. government office building. There, curator Lance Fung, who was behind the ambitious Artlantic project in Atlantic City, New Jersey, explained his Nonuments public arts exhibit. Fung said with the help of the “best neighborhood” and local partner, Washington Project for the Arts, “the community now has a temporary art park.” He made a point of saying “we didn’t phone in these works of art; they all came out of the soil of this place.”

To lay the foundation for this art park, artist Peter Hutchinson threw a rope and plotted natural material along its path — in this case, 33 trees.

Four other works seem to orbit this central work. One is Migration, a set of otherworldly “nests” by artist Cameron Hockenson, who explains: “these nests are much like neighborhoods now on the move, embracing, adapting, or resisting forces of gentrification now sweeping the city.”

There’s also Portrait Garden by Jennifer Wen Ma, a painter who magnified a picture of a local resident, chosen at random through a lottery, into a large-scale portrait through an unusual material: ink-stained plants. Ma wants to honor the “unsung heroes of daily life with plants that, like every life form, are under daily stress.”

But here, Ma has added extreme stress, coating the plant’s leaves in ink, like they are rice paper in a Chinese brush painting. Ma explained that this was part of the meaning of her work. The plants, like people, will either succumb to or overcome their challenges. I expressed concern for the plants, but she said, “they prove to be amazingly resilient. The same plant can come back year after year. They will survive if they are watered.”

And the most arresting piece was Peep by artist Jonathan Fung, which aims to use art to increase awareness of human trafficking, a dark undercurrent of humanity that also runs through the District. Fung told me that there are now more people enslaved at any point in human history, more than 30 million, and the district is a hub for this activity. In his piece, a shipping container, which is a common means of transporting trafficking victims, is painted bright pink, like something that would appeal to a child. This is because vulnerable foster children or young adults in this country — and around the world — are often the targets of trafficking, lured by people pretending to be their friends. Fung said the piece represents “stolen innocence, lost childhoods.”

Inside Peep are rows of sewing machines and a recording playing their droning music. Fung said, “it’s about the commodification of people.” Being in there working on the piece, Fung said he also now understood why so many trafficked people don’t make it on their long journeys: The shipping containers are unbearably hot. (Learn more about human trafficking in Fung’s film, Hark, or this TED talk).

Many more pieces not covered here are on view until December.