The tiny settlement of La Conchita, California, is one of those places that are at once utterly rational and crazily perverse. A neat oblong of ten streets perpendicular to the Pacific Ocean, it is almost as simple and idyllic as a seaside village could be—except that between La Conchita and the ocean lies the Ventura Freeway and a railroad. Until a few years ago, when a pedestrian tunnel was dug under the road, many residents chose to duck through a long storm drain instead of sprinting across six lanes of traffic when they wanted to watch the sunset on the usually deserted beach.1 La Conchita is hugged by mountains and is as close to the ocean as it is possible for non-millionaires to get anywhere between San Francisco and Mexico. It brought Roger Brown closer to the man he loved, whom he had lost only years before. It was the place in which he chose to draw closer to death, in an imperfect paradise of his own devising.

Brown first visited this stretch of coast in the summer of 1983 with his partner, the architect George Veronda, who had spent his adolescence in nearby Carpinteria, five miles up the highway. It was not the artist’s first visit to California. He had traveled there in 1968, and in 1980 he had an exhibition of his paintings at the University of California, Berkeley. Since the late 1960s, when Brown had been included in an exhibition called “False Image” at Chicago’s Hyde Park Art Center, he had been associated with the group of artists known as the Chicago Imagists. (The name, coined by the critic Franz Schulze, was seldom self-applied by its artists.) Although he had never been a household name exactly, Brown’s professional profile had grown steadily over the years and, with it, the opportunity for travel.

This latest trip to California accrued added significance because, shortly after the pair returned home to Chicago, Veronda was diagnosed with lung cancer. When, the following year, he passed away, Brown was utterly shattered. They had been together since 1972, and it is obvious, in Brown’s protean sketches and notes, what a generative meeting of creative minds their partnership had been. 2

Roger Brown (left) and George Veronda with their dog, Babe, in New Buffalo, Michigan, c. 1982. Photographer unknown.

Roger Brown (left) and George Veronda with their dog, Babe, in New Buffalo, Michigan, c. 1982. Photographer unknown.

Brown spent the next two years almost exclusively in the lakeside home and studio in New Buffalo, Michigan, that Veronda had designed and built as a retreat a few years before. He was not yet old, but he was growing weary of the Midwestern winters. Then, in 1988, at the age of 46, he was diagnosed as HIV positive. He later wrote, “I suppose on learning of HIV one could just stop everything—stop living and get ready to die. But why prepare to die […]? When you’re dead all the past preparation in the world doesn’t help your present condition. I chose to prepare to live.”3

Brown resolved to head for the sun. After considering properties on the Gulf Coast of Florida and in Albuquerque, New Mexico, he bought a plot of land in La Conchita, at 6754 Ojai Avenue—the street at the furthest end of the village. There was no house on the lot, but there was a magnificent trailer home: a 1955 Spartan Royal Mansion. After the Second World War, the Spartan Aircraft Company, then owned by J. Paul Getty, had shifted its manufacturing from making aluminum-skinned aircraft to making luxury aluminum trailers.

The top-of-the-range Spartan Royal Mansion was fitted inside with wooden paneling, and after Brown reupholstered the soft furnishings and added some of his own mid-century accessories, he found it so comfortable that he decided to retain the trailer as his living quarters and to build a studio on the adjacent land. Today, the trailer is parked, surrounded by plants, in the yard behind the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City.

The Spartan Royal Mansion trailer at the Museum of Jurassic Technology, Culver City, CA. Courtesy of Nicholas Lowe

Stanley Tigerman was an acquaintance of Brown and Veronda’s from Chicago—he also had a weekend home in Lakeside, Michigan, near New Buffalo. He had made his name as a member of the Chicago Seven, a group of postmodern architects who emerged in protest to a 1976 exhibition about Chicago architecture that gave undue emphasis, they felt, to the influence of Mies van der Rohe. At the time, Tigerman’s Lakeside home—which he designed in 1983 with his wife, Margaret McCurry—was one of his most celebrated designs. The house is classic Postmodernism: Clad in corrugated steel and with a white trellis covering one facade, the stark form of the main building with a Romanesque clerestory roof references both a rural barn and an Italian basilica.

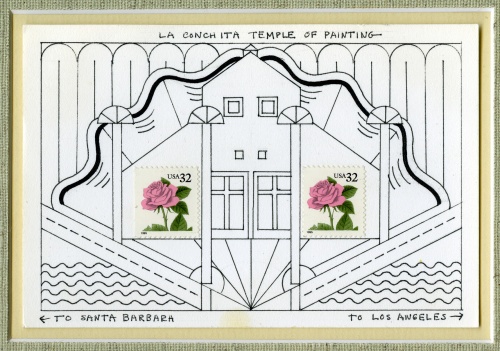

It is not clear whether it was Tigerman’s or Brown’s idea to replicate that basic shape in La Conchita. A sketch by Brown from the late 1980s shows two clerestory barn structures, one larger than the other, with the Royal Mansion wedged in between. The smaller barn, open at one end, would serve as a garage or a carport, and in later plans, it came to enclose the trailer entirely. The building would come to be known as the Temple of Painting. 4

It seems that the planning commission objected to some of the building specifications submitted by Tigerman. The local community was largely suspicious, too. For one thing, they could not fathom why the building, which was coded as residential, should have a polished asphalt floor. Inside. Nor were they happy about Tigerman’s choice of unpainted corrugated steel for the house’s walls. The retention of the Spartan trailer gave them additional concerns about the appropriate use of the land. Brown attempted to explain to the commission the unorthodox live-work situation under which he operated as an artist, but it remained unmoved.

Roger Brown, Citizens Killing Themselves After Having To Deal With the Ventura County Coastal Planning Commission (if you’re dreaming of California it doesn’t matter where you played before California is a whole new game), 1988, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 in. © The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brown family.

In 1989, Brown painted a picture showing an inverted ziggurat of boxlike offices, each containing a figure seated at a desk with hands clasped. It is dusk, and the light is fading on the horizon behind a row of silhouetted palm trees. Outside the offices, in front of six parked cars crammed with waiting families, six corpses are stretched out on the sidewalks. Two more figures are holding guns to their own heads, one as it closes an office door. The full title of the painting is titled Citizens Killing Themselves After Having to Deal with the Ventura County Planning Commission (if you’re dreaming of California it doesn’t matter where you played before California is a whole new game). 5

Finally, in 1991, permission to build was granted on the condition that the house’s floor would consist of poured concrete, the walls of the building be stuccoed (in keeping with traditional homes in the region), and the Royal Mansion was kept out of sight. Brown’s Temple of Painting was completed two years later, in 1993. Inspired by the color of the La Purisima Mission in nearby Lompoc, which Brown and Veronda had visited together, the stucco walls were painted salmon pink contrasting with a gray corrugated roof.

When he first acquired the La Conchita property in the late 1980s, Brown had raked gravel around the trailer to approximate a Japanese Zen garden, punctuated by several judiciously placed rocks and a border of roses. As Tigerman’s building was completed, Brown began to populate the surrounding areas with cacti, succulents, and native and non-native shrubs. Things accrued in ceramic pots and large planters: A Japanese maple, a fig, an orange tree, aloe, agave, and prickly pears all jostled together. He also kept a pair of caged peacocks, to the likely chagrin of the surrounding community. Along the house’s street frontage, Brown planted a line of six Washingtonia robusta palm trees (a motif echoed in paintings such as Citizens Killing Themselves), which, at the time, reached only the upper-story windows. Today, the tall trees are prominent across La Conchita.

Roger Brown Residence, La Conchita, CA; architect Stanley Tigerman, 1988.

Brown was a serious and discerning collector, although he had never had much regard for conventional hierarchies of value. His Chicago and New Buffalo homes were crammed with vintage toys and curios, tramp art, folk art and antiques, drawings by Joseph Yoakum and elaborate birdhouses by Aldo Piacenza. His strict Southern Baptist upbringing left him with an aversion to religion but a weakness for religious kitsch.

When he moved to La Conchita, he had the opportunity to start a collection from scratch. Most of his ceramic purchases were from thrift stores near his home, although he also owned collectible mid-century Russel Wright dinner services and pieces of skilled art ceramics. Many items were folk and tourist pottery from Mexico, particularly dripware from Oaxaca and soft red clay vessels from Tonalá in the west of the country. Together with his friend, the Mexican folk and popular arts expert Linda Cathcart, he trawled the thrift stores in the Mexican neighborhoods of nearby Santa Barbara for the choicest vernacular pieces.

Before Brown moved to La Conchita, his collecting and his painting had remained materially separate practices, even if they were ideologically conversant. In the most significant body of work that he made in California—a numbered sequence of nearly thirty object-paintings that he called the Virtual Still Life series, made in 1995 and 1996—he radically married the two. Each piece featured a wooden shelf fixed beneath a specially painted background; lined up on the shelves were items selected from Brown’s collection of ceramics.

He had made comparable constructions years before, although he had always implied a much more literal relationship between image and object. The first obvious precursors came in 1979: a piece called Lewis and Clark Trail, in which a painting of concentric rings of tree stumps is joined by a low shelf bearing three cross-sections of real wooden tree trunks. Another painting called Visit the Oregon Coast, from the same year, had stuffed seagulls placed in front of it.

Roger Brown, Virtual Still Life #5: Elegant Pot With Gold Sky, 1995, oil on canvas, mixed media, 26 x 31 x 8 1/2 in. © The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brown family.

With the Virtual Still Life paintings, however, Brown moved beyond the museum diorama principles of these earlier object-paintings, in which one level of unreality (a taxidermied animal, most often) is contrasted against a greater level of unreality (a painted background). Instead, when he places a ceramic vessel in front of a receding cloudscape, for example, as he does in Virtual Still Life #5 Elegant Pot with Gold Sky (1995), he is casting the pot as a protagonist in a metaphorical drama. Many of these works call to mind those paintings of Caspar David Friedrich in which a figure turns away from us, the real human viewers, to contemplate the depicted landscape. In Friedrich’s iconic The Wanderer Above the Mists (1817–18) a frock-coated man—a stand-in either for the artist or you the viewer or Colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken of the Saxon infantry, depending on who you read—gazes over a sublime mountain range.6 In Virtual Still Life #5, the frock-coated man is replaced by a softly glazed, asymmetrical piece of art pottery. Given Brown’s predilection for the dignified but unassuming mass-produced item, it seems likely that his designation of that art pot as “elegant” in Virtual Still Life #5 is meant as gentle mockery of its aspirations.

Roger Brown, Virtual Still Life #8: Vases With A View, 1995, oil on canvas, mixed media, 25 x 25-1/2 x 7 in. © The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brown family.

This personification is only really half the story. Perhaps not even half. In most Virtual Still Life paintings, the shelf holds not one but several items—a whole landscape of pottery. In many cases, the colors of the painted backgrounds match precisely the tones of the ceramic glazes, suggesting that these conjunctions of image and object are not meetings of the self and the other, or reality and artifice, but are in fact seamless syntheses of pattern and functionality, and of fine and applied arts. What else is ceramic but clay from the earth, after all?

The transformation that takes place, as so often in Brown’s work, is one of scale: the hand-thrown mug that is as high as a mountain, or the bowl that is as broad as a plowed field. Along with the plants in pots throughout his garden, Brown collected bonsais, a plant that appealed to this ongoing fascination with the disorienting possibilities of scale. In 1997, at the very end of his life, he painted a series of pictures in which the exaggerated and sometimes distorted forms of bonsai trees dwarf tiny human figures, as if the trees were not just life-size but colossal natural specimens like the giant sequoias and redwoods that tower over tourists in other parts of California.

Roger Brown, Another Shitty Day in Paradise, 1993, oil on canvas, 72 in. x 48 in., Iris and

Roger Brown, Another Shitty Day in Paradise, 1993, oil on canvas, 72 in. x 48 in., Iris and

B. Gerald Cantor for Visual Arts, Stanford University.

Not all his paintings included shelves and objects; before the Virtual Still Life works and the Bonsai series, he made a number of paintings that responded in ironic ways to the curse of Southern California’s blandly blue skies. Brown had always been interested in weather, often using clouds to conjure portentous, unsettled atmospheres. Another Shitty Day in Paradise (1993) is a painting of rolling green hills with tiny houses nestling between. Overhead, huge black clouds have formed themselves into two massive pompom balls with teddy bear or Mickey Mouse ears attached. The picture, like others in the same series, appears as a dreadful warning against the homogenization of American mass culture and the leveling of the playing field of aesthetic entertainment.

In the light of Brown’s advancing illness, it is also possible to read the cloud forms as menacing, mutant penumbrae that, even on apparently clear days, were looming on the artist’s horizon. There is no doubt that he was preparing to face his own death. In his New Buffalo garden in 1993 and 1994, he planted 204 rose shrubs in 86 varieties and also produced a series of four Rosa paintings. Rosa Foetida Bicolor (1994) shows three squat rose bushes beneath a swirling, ominously dark sky. (Rosa foetida is a variety named for its unpleasant smell.) In Rosa Californica (1994), wild roses grow incongruously on what looks like a fat four-stemmed cactus. All is not well in these images; despite Brown’s creation of a personal idyll in La Conchita, it is clear that the increasingly sick artist had his mind on forces of natural darkness as well.

In 1995, he donated his cherished New Buffalo home and studio, along with the collection that it contained, to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in order that it be used as a retreat for faculty and staff. A year later, he gave the bulk of his remaining collection, installed in his Chicago home on North Halsted Street, to the SAIC, which agreed to buy the building in order to house it. The Roger Brown Study Collection was founded with this gift and remains active to this day.

In other important ways, Brown was not preparing to die but, as he had written, preparing to live. In the last two years of his life, he produced an extraordinary number of architectural plans for buildings and landscapes that he seemed determined to realize. He bought land close to the pink mission in Lompoc, seventy miles up the coast, and made detailed plans for a three-room adobe home and studio that was inspired by the Gallegos House near Santa Fe in New Mexico.

The Roger Brown Study Collection at 1926 N. Halsted Avenue in Chicago

© The School of the Art Institute of Chicago

More ambitious still, he made a number of plans for the landscaping of an expanse of land adjacent to his parents’ home on Glenn Street in Opelika, Alabama, and building a house for himself there. The plans went through several stages of refinement, but in the final version, a two-story “antique house” was to be moved from a location across town onto the Glenn Street property and reconstructed. Palm trees line the drive, and a network of streams connect to a central pond. On the grounds, a greenhouse, a painting storage facility, and a Nantucket barn are situated among a cotton field, a rock garden, a wildflower meadow, woods, a vegetable garden, and trees, including lilacs, cypress, smoke trees, and pecan. Brown’s mother had understandable reservations about these plans, which nevertheless deeply disappointed him, and they remained unrealized.

As a second recourse, he persuaded the owner of a house he had long admired in Beulah—a few miles out of Opelika—to sell. In 1997, as his health faded, he made plans for his use of the building, known as the Rock House, with a studio on the ground floor and living quarters up above. He ordered appliances and furniture and organized the transfer of some of his collections to Alabama.

He knew that he must leave La Conchita forever in order to spend whatever time he had left close to his family. His friend Linda Cathcart recalls how, after finding a good home for his beloved white bulldog, Elvis Whitedove, he tidied the Temple of Painting for the last time, cleaned out the refrigerator, and filled bowls on the living room table with candies. A month and a half later, on November 22, 1997, the day before he was to sign the transfer papers on the Rock House, Roger Brown died.

Roger Brown home/studio, La Conchita, CA, 1998. Overview, living room, east view. Photo: Roger Brown Study Collection

© The School of the Art Institute of Chicago

As with almost all of his estate, Brown bequeathed the house in La Conchita and its contents to the SAIC. Only a thin sliver of Brown’s enormous ceramics collection made it into his Virtual Still Life series; the rest remained on shelves and hutches in his home and studio. Some even overflowed into the garden: When he left La Conchita, there were at least two hutches of ceramics in the carport. The institute reluctantly sold the house in order to fund the maintenance of the two properties in Chicago and New Buffalo. The entire contents of the house and garden, including all the ceramics, were shipped to Chicago, where they are preserved by the Roger Brown Study Collection. That Spartan Royal Mansion—the seed of Brown’s Californian Shangri-La—presented a dilemma to the SAIC until the Museum of Jurassic Technology, which already owned a smaller, Spartanette trailer, offered to take it into its care. Today, the trailer is used by resident artists as a living memorial to Brown.

We do not know for sure whether Brown believed in heaven. He was vocally critical of organized religion, especially of hypocritical evangelist preachers like Oral Roberts, but he remained a spiritual soul.7 He spent a lifetime imagining and building earthly paradises, along with their inevitable flaws and contradictions. Through his paintings, his homes, his collections, and gardens, many of those paradises remain today.