Mickalene Thomas started out as an abstract painter, inspired by Australian Aboriginal art and late-nineteenth-century French Pointillism. She had always incorporated found materials into her work, but when she got to graduate school she began to make representational paintings using glitter—flashy animal personifications with punning titles like Black Cock Black Bitch. For a performance-art-history class in graduate school, she decided, as her final project, to embody an alter ego, Quanikah, which was her childhood nickname. In the staid precincts of Yale University, she presented herself as a sexy urban black girl, confusing fellow students and faculty who mistook her for a lost resident of New Haven. A photography teacher urged her to explore a subject close to her, one that came “from a vulnerable place,” and after initial resistance she decided to focus her lens on her mother, Sandra Bush, from whom she had been estranged. Thomas would later say, “The moment I started photographing my mother was the moment my work completely changed.”

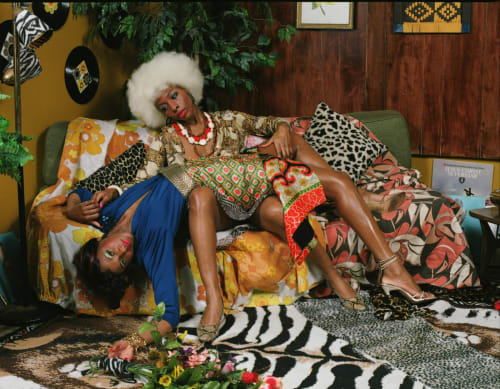

In her early photographs of Mama Bush, and of herself as Quanikah, Thomas revels in a theatrical form of feminine display. The makeup, hairstyling, and outfits of both women evoke the nineteen-seventies, when Thomas was a little girl and her mother was an aspiring model. Both personae represent a highly artificed femininity, celebrating black beauty by accentuating lips, hair, and breasts with enamels and powders, eye-catching colors, and seductive textures.

Over the course of the next ten years, Thomas’s complex investigations extended to representations of other women in her life: initially to her girlfriend, the object of her affection; then to female friends and acquaintances; and finally to an expanded field of trans women, all linked in their reflection of the seventies styles their mothers once wore. She describes her process as collaborative, working with her subjects to find the pose that is uniquely comfortable to each of them. With these muses, Thomas says, she sets out to capture “the exact moment when I sense her satisfaction of taking on a role and representing some aspect of her character through that role.”

In Roland Barthes’s reverie on photography, Camera Lucida, he muses at length about an image of his mother that the reader never sees. This phantom picture is at the core of his ruminations on photography, and yet he does not illustrate it because, as he writes, “It exists only for me. For you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture.” For Barthes, the truth of the photograph lies in the way it captures his mother’s air, her characteristic gestures and poses, and her gaze at a specific moment, a time both historical and present. For Mickalene Thomas, too, the power of the photograph resides in the gesture and the gaze, and, as it did for Barthes, in her relationship with her own mother, who passed away in 2012. A daughter’s love is transmuted to a love for photography, with its unique ability to create the delirious, uncanny sensation that the person in the picture, now just a memory, lives on.

In a recent interview, Thomas said, “By being my muse, [my mother’s] become the person she’s always wanted to be.” Perhaps also the person the daughter wanted her to be? A few years ago, in response to a question about the qualities she looks for in her muses, Thomas explained that she is drawn to confidence and self-awareness, as well as to “beauty, a little uncertainty, perseverance, and a sort of hunger. All of the stronger qualities I feel I possess. I guess I look for myself in these women.” Mama Bush’s beauty is indelibly preserved in her daughter’s ideal photographic images, enduring memorials to her mother, the pivotal muse in her work, her mirror reflecting a gaze between two women, and the self.