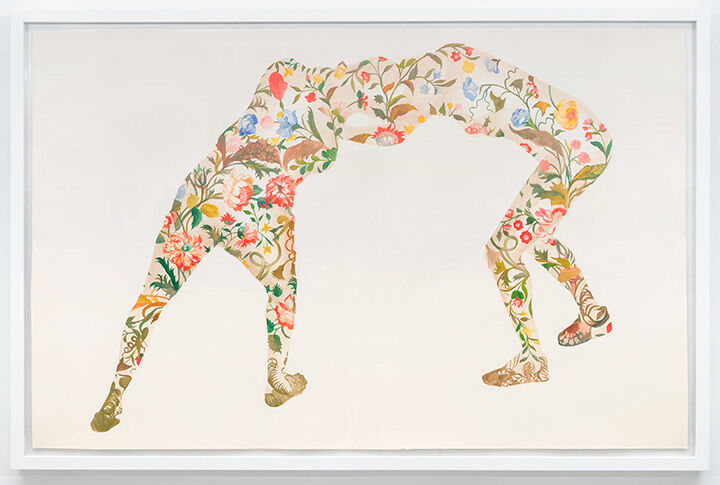

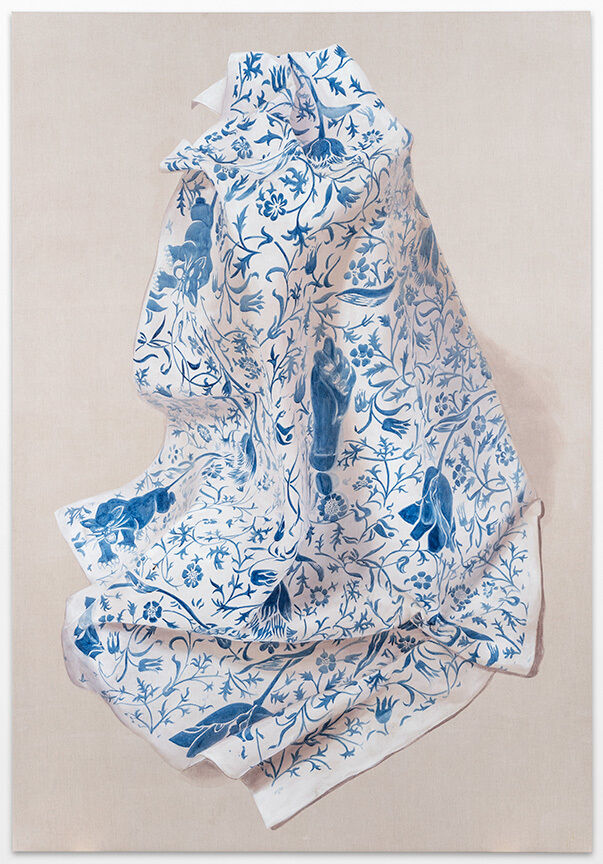

Báez is Dominican by birth and resides in New York, a diasporic context that could be easy to overemphasize in trying to make sense of her work, but that nonetheless must be acknowledged given her many explicit references to it. The primary experience of “Bloodlines,” however, is one of overwhelming aesthetic beauty. Báez moves effortlessly between mediums—often within the same works—mixing abstract washes of paint with intricate drawings, an exacting eye for archival materials with an exuberant, impressionistic handling of color and gesture. Patterns abound. Based on flora and fauna, strict geometry and swirling mandalas, these visual rhythms soar in their current installation under the southern Atlantic light. They draw you in close and yet cannot help but evoke the Caribbean islands just over the horizon.

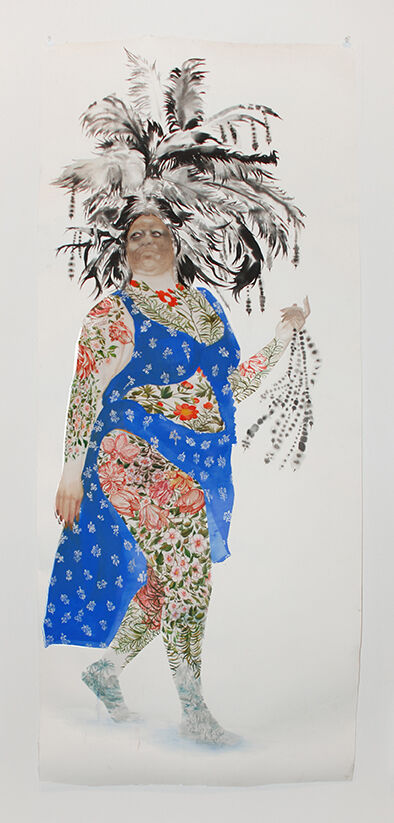

The works’ ornate, colorful designs are not simply there for our visual consumption, delectable as they might be. In many cases, they converge into powerful female figures, saved from complete abstraction by their piercing eyes and distinctive fashions and hairstyles. In other cases the opposite dynamic is at play, and a closer inspection of the patterns reveals symbols and narrative vignettes that reference the experiences of African-American and Afro-Caribbean women—scenes of subjugation and, more frequently, radical self-making in the face of it. It’s at this point that the real politics of Báez’s work surfaces, delivered to your consciousness in opulent, impeccably made packages.