This article originally appeared on Creators.

Tackling pop-cultureTackling pop-culture with high-art sensibilities, Mickalene Thomas' work spans painting, photography, collage, and film. Her art is in MoMA's permanent collection, and it lines the Lyons' walls in Empire. Throughout the diversity of her practice, one theme is near-constant: black women.

She creates portraits of everyday black women and notables like Oprah, Michelle Obama, and Solange Knowles. Through her gaze, black women are powerful, beautiful, all-encompassing. We're the sole inhabitants of the collaged, painted, and bejeweled world she renders in her works. Thomas depicts us posing like classical nudes and posting like 70s Blaxploitation pin-ups.

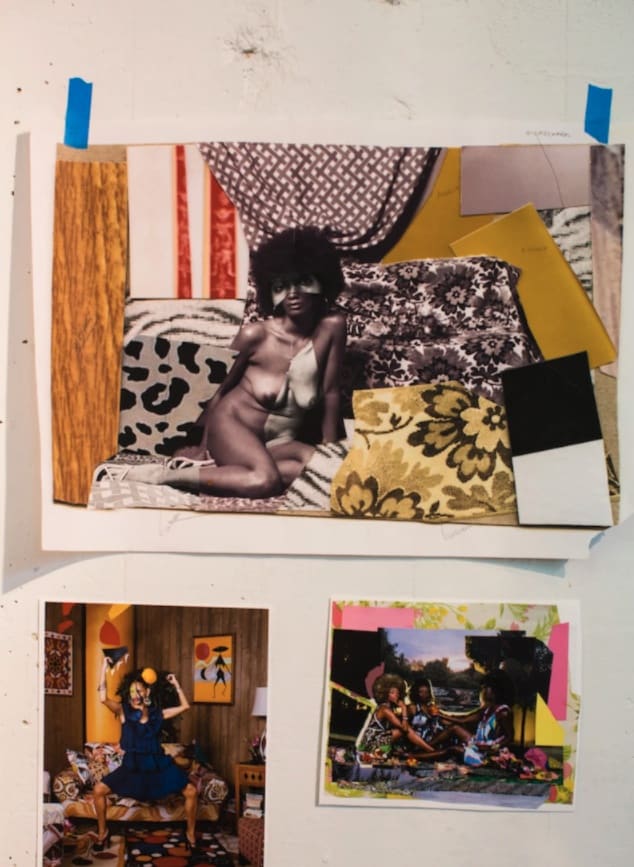

The New Jersey-born artist's studio is a tidy, spacious machine. As she shows me around, she stops at one workstation or another, observing the work of her assistants, telling them she liked the way the work was coming along. We pause before a giant collaged work that spans the greater part of one of the studio's walls. It's a classic Thomas—a beautiful afro-wearing woman leans back on a couch, one leg planted on the floor, the other lifted in the air. It's a version of her piece Racquel Reclining Wearing Purple Jumpsuit, a mixed media collage using elements of a photographed portrait of Thomas's partner, Racquel Chevremont.

Racquel is one of Thomas' regular muses. The term "muse" is culturally loaded, the artist-muse relationship complicated by the power dynamics of the people who generally inhabit those roles—the white male artist and his passive beauty object, who's almost almost always a white woman. Still, Thomas embraces the term, using it to describe the friends, girlfriends, models, and family members she depicts in her work. Muse is also the title of a book of Thomas's photo portraits, and the name of the exhibit that accompanied it. When both artist and muse are both black women, the dynamic is different. "It's sensually more powerful," says Thomas.

Racquel Reclining began as a photographed portrait that Thomas shot in her studio, on a wood-paneled living room set where nearly every surface is covered with colorful retro textiles. "Building these environments allows me to compose and really feel like I'm entering the space," Thomas says. After staging the portrait, she turned it into a collage, adding glitter and painted elements that created a distorted reflection of the original image. "It's looking at the photographic image and then deconstructing that image maybe five more times, layering it, and playing with the scale," she says. Inspired by artists like Modigliani, Racquel's form is elongated in the collaged work, almost overwhelming the couch on which she reclines. "That's why I needed to make her longer," Thomas explains. "I really wanted her to feel like she is commanding her space. To me, it's like, I am in full control of every movement that I am doing while I'm occupying this space."

Thomas made the slipcovers that jacket the set's chairs and couches. She visits Salvation Army shops and thrift stores looking for fabrics that catch her eye. Old house dresses are among her favorite sources for cloth. "I love using house dresses, my grandmother used to wear house dresses," she says. "Do you know why? Because there is something about the fabric and the softness from women wearing it that I love." My grandmother and great aunts loved wearing house dresses too, so I know exactly what Thomas means. Housedresses are icons of a powerful domesticity, of knowing matriarchs. By incorporating them in her work, Thomas taps into a tradition of commanding womanhood.

"Someone had spent time with this," Thomas says, running her hands over fabric cut from a housedress. "It's worn, the color is deteriorated, it's faded away. It has this really beautiful softness to it, like your grandmother's skin."

Though Thomas is best known for her mixed-media paintings and collages, new works find her branching into film. Her show, Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities, is currently on view at the Aspen Art Museum, and consists of video pieces. Hunched over a computer in her studio, Thomas shows me one of the works that's in the show. It's a four-channel video piece based on Eartha Kitt's performance of "Angelitos Negros," or, "Little Black Angels," a song that finds the singer wondering why, when she enters a church, she only sees images of white angels. She implores painters to paint black angels for "all good blacks in heaven." Thomas' take on the video features herself, Racquel, and an actress, all reenacting Eartha Kitt's performance alongside Kitt's original, their four voices intertwining for the audio.

"How come you don't paint our skin?" Kitt, Thomas, and the other women ask in song. Even though the work positions Thomas as an observer of art, in reality she is one of the painters to whom the song begs representation. Her every work is an answer to the song's plea—Mickalene Thomas is forever painting our skin.