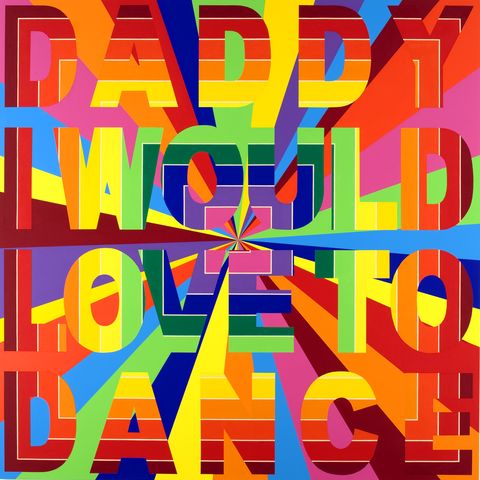

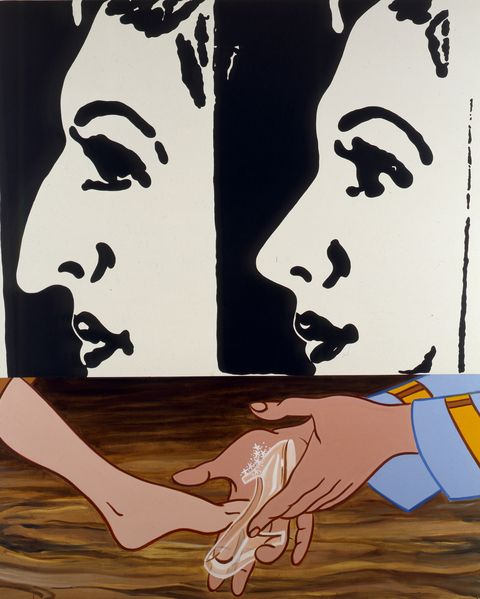

Deborah Kass takes in the world around her and distills it meaningfully into her artwork. This process was how she found her creative voice—using the language of art history as a starting point for her own expression. Her practice has spanned more than five decades across painting, photography, sculpture—even neon light installations. But her most recognized style is often a pop cultural spin on the artistic greats who came before her—from Eugène Delacroix and Pablo Picasso to Jasper Johns and Jackson Pollock. In both homage and critique, Kass’ paintings rewrite their work through her lens, infusing them with Disney cartoons, female artist icons, and texts on gender and identity.

The Texas-born artist (b. 1952) found worlds of inspiration in New York, the city where she was raised. By the time she was in grade school, Kass decided to pursue an art career. She took drawing classes at The Art Students League and spent hours in the city’s storied museums—which now aptly house her own artworks. She pursued her dream through drawing classes at The Art Students League and hours spent in the city’s storied museums—which now aptly house her own artworks. She studied painting at Carnegie Mellon University and later at the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. In the years since, she has made an indelible mark on the art world as an outspoken voice for change, often tackling social equality through her art.

Here, CR speaks with Kass about revising women’s narratives, why power—and art—are always political, and the female figures who were visions for who she could become.

"I actually consider them to be more first loves. I was exposed to them at a very young age, when I was figuring what it meant to be an artist. They were the people in museums at the time and that was how I got to know their work. The people who actually inspired my work as a conscious artist are Pat Steir, Elizabeth Murray, and Joan Snyder, basically the New York school of painting in the '70s where it intersected with feminism. These artists showed me how to use a language I had learned and make it speak for me. That's what they were doing, so that was my inspiration. It made me the artist I am because what these women did was much more about what I wanted that language to say. Faith Ringgold used materials that were not usually associated with high art, Adrian Piper was operating in conceptual art and philosophy. Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, and Cindy Sherman took a deconstructive approach to power and photography that has also informed what I do."

How has your work been a platform for equality within the arts?

"I was always interested in post-war painting in New York and looking back on how power and value are established in art in general. I wanted to see from my point of view and think about how I could use that language to reflect my own viewpoint, to talk about something other than the assumed value and the benefit of the doubt that was always given to white men. I have said it before but it is really the best explanation of it—I used art history as a readymade and made it speak for me. Post-war American painting was my first love, it was what I saw at MoMA when I was 16. I am always very loyal and grateful to my first loves."

"People of my generation really appreciate women of younger generations' ambition. Personally, I am obsessed with Sarah Cooper. For someone like me, it's a joy to see and I am proud of these women. They are often the daughters of my generation, and men who had a very hard time with women’s roles before seem to have a new appreciation of it with their own daughters."

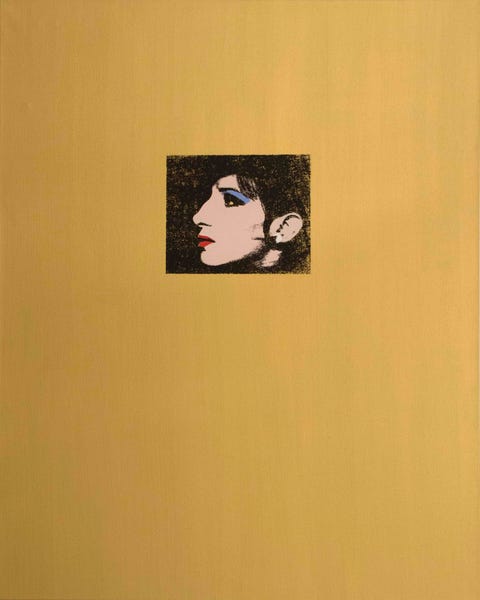

What did figures Barbra Streisand and Gertrude Stein mean to your creative expression?

"Speaking of ambition, they were fantastic role models for me. Barbra was out there at 20 years old expressing ambition, vision, and control. Identifying with her was so important. It's also why we love Madonna—because she went on [the Late Show with David] Letterman and said, 'I want to rule the world.' Gertrude [Stein] was a more mature and literary love that came later. My interest was from her portrait by Picasso that I saw at The Met when I was young, but it developed more in my 20s. She was another picture of female, Jewish ambition. She said, 'I am a genius' and she was profoundly centered on it. I had an aspirational identification with these women. I aspired to their ambition, their genius, and how they unapologetically owned these qualities."