In the Boyle heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, tucked between a gas station and what looks to be an abandoned warehouse, sits a former ceramics factory that now houses the studio of Glenn Kaino, a prominent conceptual artist. One morning in April, Kaino opened the back door and ushered inside the Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith; Smith’s wife, Delois; and me. We were greeted by an imposing stack of 70 or 80 cardboard boxes. “What are those?” asked Smith, who at 6 foot 4 towers above Kaino. “Arms,” Kaino responded. “Those are all arms?” Delois exclaimed.

The arms are not just any arms, but fiberglass casts of Smith’s actual right arm, made from a silicone mold that Kaino took a few years back. Dozens of replicas are now strewn across the studio, in various states of preparation. Each one extends from the shoulder to a gloved fist, every vein, and ripple of muscle discernible along the way. When any of the arms is held upright, its significance is immediately evident.

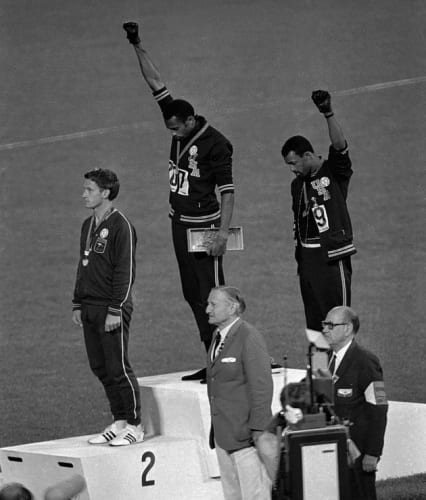

Tommie Smith was once among the fastest men on Earth. During his sprinting career, he held 13 world records (11 of them simultaneously). He set the most famous of these on October 16, 1968, when his 19.83-second 200-meter dash at the Mexico City Olympics earned him a gold medal. His countryman and college teammate John Carlos won the bronze. When the two Americans mounted the podium to receive their medals, “The Star-Spangled Banner” blaring over the stadium speakers, each bowed his head and raised a black-gloved fist—Smith’s right, Carlos’s left. Around the stadium, jaws dropped and cameras flashed. Their protest, which was interpreted by many viewers as a Black Power salute, remains one of the most iconic images in the history of sports.

Several years ago, a friend of Kaino’s noticed a photo of that salute taped to his computer screen. (Kaino has an abiding interest in social protest: Another recent work of his, titled Suspended Animation, features a conveyor belt dotted with rocks collected from the sites of recent political protests, including Egypt’s Tahrir Square and Ferguson, Missouri.) The friend mentioned that Smith had been his coach in college and offered Kaino an introduction; within days they were on a plane to Atlanta, where Smith now lives. Once there, Kaino proposed an art collaboration and politely asked whether he could “take the arm off your body.”Smith agreed, and Kaino has used the resulting mold to turn out a whole collection of arms. The ones that were packed in boxes on the day of our visit were from a work called Bridge, which had just returned from an art show. When installed, dozens of the limbs—painted gold, like Smith’s medal—hang from the ceiling in an undulating pattern, each one parallel to and at a slightly different elevation than the last. As one critic put it, the effect recalls “vertebrae in a paleontological exhibit.” “We’re using the arm to indicate continuation,” Smith said, referring to what he sees as continuity between his protest and the present moment—a time of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, of Black Lives Matter, of renewed discussion about race in America.

The work’s latest home is the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta, where it is part of a larger exhibit by Kaino and Smith, called “With Drawn Arms.” “The image that [Smith] created was so powerful that it kind of flattened him into this one 90-second moment,” Kaino told me. “What we’re trying to do is re-dimensionalize him.”

Smith was born in 1944, the seventh of 12 children. His father was a sharecropper, first in Texas and then in California; Smith grew up picking cotton and grapes when he wasn’t in the classroom. In high school, he played basketball and won a scholarship to San Jose State University, where he contemplated becoming a three-sport athlete before settling on track. San Jose’s team was at the time amassing top talent, earning it the nickname “Speed City.” Smith thrived, tying two world records—the 200-meter dash and the 220-yard straightaway—in his sophomore year.

Immediately after running those races, Smith headed to a protest march he knew about through a student athlete turned activist named Harry Edwards, with whom Smith had bonded over a mutual respect for education (“You can’t eat speed,” Smith recalls Edwards telling him). It was 1965, and the civil-rights movement was in full swing; inspired by Malcolm X, Edwards had decided to organize student athletes to protest racial disparities at San Jose State. Smith was an early and staunch supporter of Edwards’s movement, which quickly grew beyond campus. In 1967, as the Mexico City Olympics approached, Edwards formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights with a handful of athletes. The group threatened an athlete boycott of the Games—though Edwards says its real goal “was to change the total perception and understanding of the role that sports played in black life in this country.”

The athletes ultimately decided to attend the Olympics, clearing the way for Smith and Carlos to win their respective medals and stage their demonstration. The protest was meticulously thought out: The men wore scarves to symbolize lynching; black socks and no shoes to symbolize poverty; and gloves, Smith has said, to represent “freedom and power; equality.” They also had on Olympic Project for Human Rights pins, as did the silver medalist, a white Australian named Peter Norman, in solidarity.When Smith and Carlos raised their fists, the stadium and the world went quiet. “For a few seconds, you honestly could have heard a frog piss on cotton,” Carlos wrote in his autobiography. “There’s something awful about hearing fifty thousand people go silent, like being in the eye of a hurricane.”

The shunning that followed the silence was even more difficult to bear. Both Smith and Carlos were barred from future international competition, effectively ending their sprinting careers. “I never would know how fast I could have become,” Smith later wrote in his memoir. “I would have just turned 28 by the time of the 1972 Olympics in Munich, and everyone has seen what runners like Carl Lewis and Michael Johnson have done as they matured.” Back home, the men were ostracized not just by white Americans but by many black people who feared being associated with them. Hate mail and death threats piled up. Smith got one letter telling him to “go back to Africa,” complete with a fake plane ticket. “I was knocked verbally and financially,” Smith told me.After graduating from San Jose State, Smith was able to find only sporadic employment, including a brief stint on the Cincinnati Bengals’ backup squad. Smith says he could barely afford to supply his infant son with formula during this period, and the resulting stress contributed to the dissolution of his first marriage. He eventually was hired as the track coach and an instructor at Santa Monica College—positions he would hold for more than two decades—but he continued to struggle. As his second marriage was falling apart, in the mid-’90s, he was robbed of tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry and memorabilia.

By then, his notoriety seemed to be fading to anonymity. Delois, his wife, told me that when she met Smith, in the late ’90s, she had no idea who he was. (Her daughters had to look him up online.) As they were falling in love, she helped him get some of his stolen items back. Smith credits her efforts with helping persuade him to give marriage one more try. After the two wed, Smith’s life turned something of a corner. In 2005, San Jose State erected a statue to Smith and Carlos—among the most public commemorations of their salute to date and one that Smith found especially moving because it had been spearheaded by a white student—and awarded them honorary doctorates. A few years later, they accepted the Arthur Ashe Courage Award from ESPN.

As we walked around Kaino’s studio, Smith paused to look at one of the latest renderings of his arm. Hanging on a wall of the studio was a rectangular box, inside of which was an upright arm (painted gold, like all the others). A mirror at the back of the box created the illusion of a series of arms repeating into the distance. “I love those arms,” Smith said. “The continuationof things.”

The reverberations of Smith’s gesture are perhaps more evident today than at any other time in the past half century, thanks in large part to Colin Kaepernick, whose practice of kneeling during the national anthem rapidly spread across the NFL, prompting backlash from President Donald Trump, team owners, and many fans. Kaino helped arrange for Smith to meet Kaepernick last fall, an encounter that was filmed for a documentary portion of their collaboration. “He knew about the stand in Mexico City,” Smith told me proudly. “He was on his knee and I was on my feet, but we represent the same thing. The brutality, inequality.”

After the 1968 Olympics, Smith was called a militant and his act was labeled an expression of black power—descriptions he’s been trying to shake for decades. He bristles at the mention of the Black Panthers (though Edwards, the San Jose State activist, was a member), and he insists that his protest was about human rights broadly. “I never focused solely on blacks to the extent that everything else was secondary,” he has written. “I did not want my participation to be about only one kind of people.” In the 50 years since what he calls his “silent gesture,” Smith believes, society has made progress toward some types of equality—Americans did elect a black president. A lot, of course, still needs fixing: More than once Smith noted to me the frequency with which African Americans are subjected to inhumane treatment in the United States. But he is heartened by the attention that activists like Kaepernick and members of Black Lives Matter have garnered lately.

Which isn’t to say the attention has all been positive. Like Smith, Kaepernick has been vilified and unable to find a job (he’s suing the NFL for colluding against him). Nonetheless, Smith believes that Kaepernick’s actions could prove more impactful than shorter-lived protests by other African American athletes over the past 50 years—among them the basketball players Craig Hodges and Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf in the 1990s. “You just keep working, it will happen,” Smith told me. “I’m not broken to a point that I can’t move forward. Colin Kaepernick is going to be the same way.”

In the meantime, Kaepernick’s protest continues to spur renewed interest in Smith’s. “With Drawn Arms” will stay on display through February 3, 2019, when Atlanta hosts the Super Bowl. “I’m expecting the audience to be much broader than we typically see,” says Michael Rooks, the show’s curator, adding that he believes the exhibit “will allow our audience to see themselves in Tommie.” Literally: One of Kaino’s favorite pieces is a life-size sculpture of Smith cut in half vertically and finished with mirrored steel. It is titled Invisible Man (Salute).

Perhaps needless to say, Smith was not invited to the White House in 1968, as many Olympians are. But in 2016 (shortly before Kaepernick first took a knee), President Obama saw fit to belatedly honor Smith by having him visit; Kaino and Delois came along. As a gift, they brought Obama a drawing of Smith passing a baton during a world-record-setting 4×400-meter relay race. On the back, Smith wrote, in part: “Most importantly, the ‘Baton’ was not dropped.”Smith returned to the White House again later that year with the U.S. Olympic team, but says that he won’t be visiting the current president. The baton has, in his view, been dropped. “But it didn’t roll out of the lane,” he added. “You can pick it up.”