The mythology and humanity of Michael Jordan, Alvin Ailey dancers and other iconic athletes are the focus of Nikko Washington's West Loop exhibition, "For The Old Gods And The New."

WEST LOOP - A series of paintings by South Side native Nikko Washington elevate Michael Jordan, Sammy Sosa and other Black athletes into the realm of mythology while exploring how their roles as modern gods can simplify and distort their humanity.

For the Old Gods and the New, Washington's exhibition of new paintings, is open through Feb. 10 at Kavi Gupta Gallery, 835 W. Washington Blvd. in the West Loop.

The pieces on display reinterpret the "Uncle Remus" tales, African folklore and other histories and myths "in a modern language with modern protagonists": Black professional athletes, Washington said.

Just as people have seen their humanity reflected in the tales of Icarus and Achilles for centuries, tales of Kobe Bryant's work ethic or Sosa's fall from grace are fables for new generations, Wasington said.

"I grew up idolizing my sports heroes, and for me, that is a part of the culture of sports in our community," Washington said. "We really love our hometown heroes and lift up our greatest of all times, our GOATs.

"I started an earlier series about my relationship with violence and boxing, and from then on, it evolved into the fight of life through sports and an analysis of racism through [the lens of] sports. From there, I truly found this spiritual connection with sports and mythology. The mythology around players is what gives them this godlike or larger-than-life feel."

The real-life subjects in For the Old Gods capture the essence of sports icons like Jordan and Sosa, but they are far from spitting images.

"I never do portraits of likeness. I'm not really trying to capture that person's image and make it for them," Washington said. "I feel like that's like fan art, in a way, and that's about [appealing] to what they want to be viewed as, rather than an accurate perception of my view of these stars."

Nikko Washington, Diety II, 2023. Image courtesy of Maxwell Evans and Block Club Chicago.

In one painting, Jordan embodies "Black Jesus" as he dons a cloak like that of Isaac Hayes on the musician's album, "Black Moses." With the modern splintering of media and popular interests, the painting seemingly questions whether anyone can achieve the unanimous acclaim Hayes and Jordan saw during their careers.

Sosa's years of skin whitening informs "How the Cub Lost His Color," which sparks debate on how the public would respond to a white athlete changing their skin tone. The piece also underscores the social pressures the Cubs outfielder faced as he became "this American icon who was not American," Washington said.

Despite the lofty concepts he explores, Washington isn't preaching to his patrons, he said. People's conclusions about his art will be shaped by their cultural experiences and their own relationships with sport and competition, he said.

"My point [with the artwork] was through my own lens - of lessons and outcomes of fame, of celebrity, of reaching this status," he said. "It's not really to critique, it's really just to present a conversation in the gallery that the viewer also can speak about."

Interpretations of athletes like Jordan, Sosa, Colin Kaepernick and Jesse Owens are featured throughout the exhibition. In a side room at the Kavi Gupta Gallery, photos and ephemera of singular Black athletes like Jack Johnson and Satchel Paige are on display, further grounding the paintings in historical reality.

"The cultural storytelling in [Washington's] work feels very relevant to our larger program, and the research aspect to his practice is something we're deeply invested in," Kavi Gupta, gallery owner and director, said in a statement.

"Our gallery has a historic archive of over a thousand photographs, as well as books and other printed matter, all pertaining to civil rights and African diasporal cultural history. Nikko was able to curate a selection of these materials to supplement the show, illustrating some of the deeper cultural threads woven through his work."

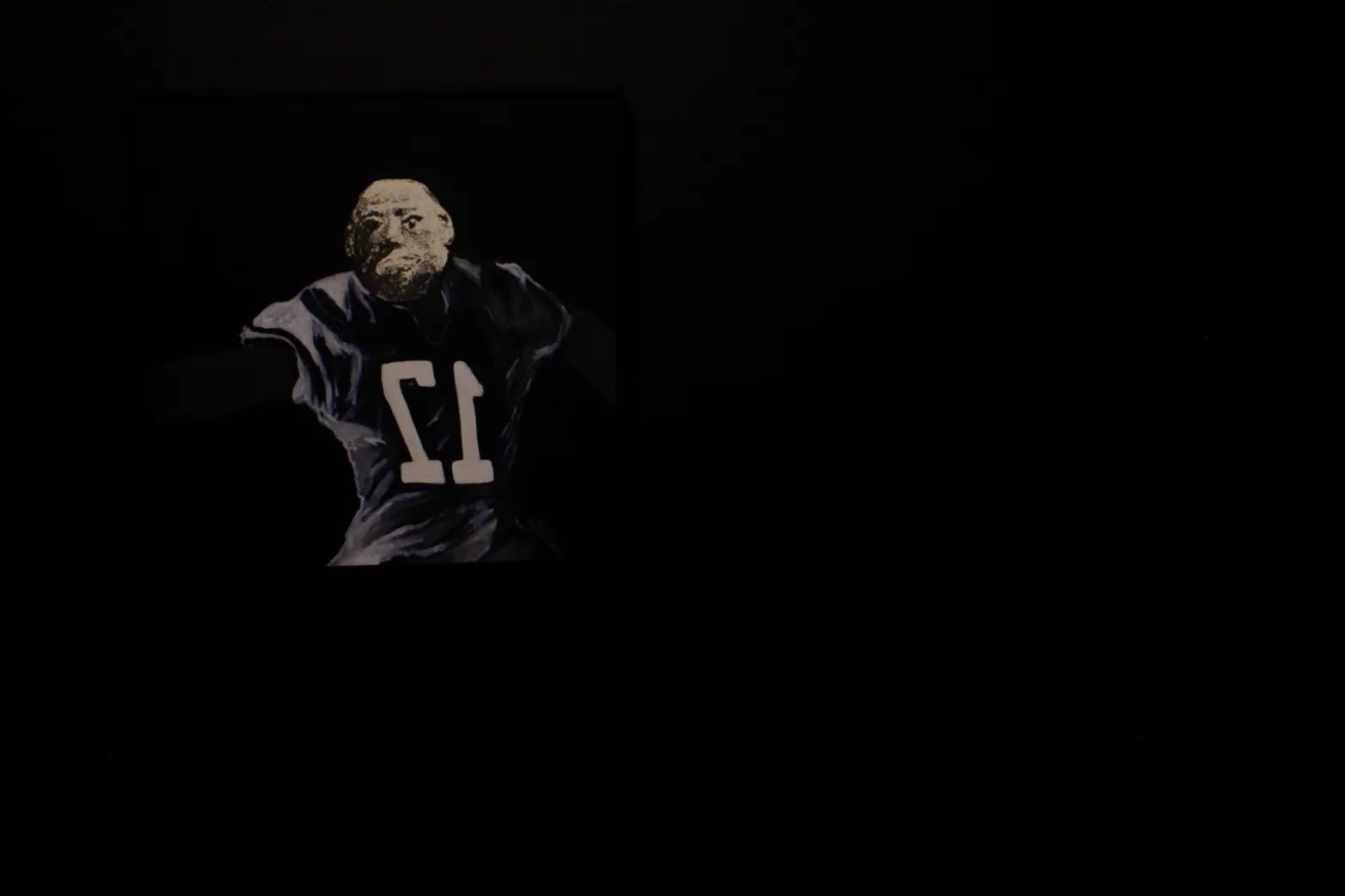

Other pieces draw inspiration from broader and more abstract sources. In the painting "Jim," a detailed crow plays the role of an athlete as a mostly featureless crowd celebrates, or maybe heckles, the bird.

Nikko Washington, Jim, 2023. Image courtesy of Maxwell Evans and Block Club Chicago.

Several works portray Black female dancers displaying their power and grace as they create new worlds and offer shelter from ominous forces. Those were influenced by Washington's sister, whose wall was lined with posters of Alvin Ailey dancers while he idolized hoopers like Bryant and Allen Iverson.

Taken together, the pieces in "For the Old Gods and the New" invite deeper conversations about how the beauty, violence and dedication athletes embody can inspire others - and reduce them to symbols rather than full human beings, Washington said.

"It's not about the sports, it's not about the athletes, it's not about the celebrity. It's about narrative behind them," Washington said. "Each era, each generation has their one star that has a target on their motherf-ing back, or a lesson in the story of how they ended up.

"All these people … you can learn a lot from [them] outside of their sport - how they were treated, what they stood for."

Washington, a Hyde Park native, credits independent boutiques like the now-defunct PHLi Store on Harper Avenue, art programs like those at the Hyde Park Art Center and graffiti crews who painted and breakdanced near his childhood home among the formative influences on his artistic career, he said.

Hyde Park is also where Washington started practicing Tang Soo Do as a 5-year-old. He credits the "controlled chaos" of the Korean martial art for instilling a sense of discipline he's carried into his art practice, he said.

"There's a big sense of community there that really nourished each other … [and] all of this stuff was just nurturing for a young artist and a young person," Washington said. "I'm thankful I grew up in this neighborhood."

For the Old Gods and the New" is not the first time Washington has portrayed the relationship between Black athletes and their mythical roles in society in his art.

Nor is this latest exhibition a final statement on the subject, the painter said. Washington has studied Greek mythology since high school, but he said the creative process has helped him "reclaim" the Black American, African, Caribbean and other folk traditions as his own.

"I found a new ocean of information and inspiration with the folk tales," Washington said. "A lot of these folk tales are just explaining how things are, like how catfish don't have any scales and [why] they look they way they do.

"These stories are very important, because while they may not be scientifically true, there's always a moral in it about the dos and don'ts of the world. I think you find that in a lot of these narratives of athletes who made the wrong choice or made the right choice - the dos and don'ts of how to navigate life as a Black person."