The ICA San Francisco’s new exhibition of 2023 celebrates the power of Black women and leisure and adornment as self-expression.

The ICA San Francisco 2023 is beginning their year with “Resting Our Eyes,” a multimedia show that positions Black leisure, adornment, and beauty as radical and necessary acts. The show, cocurated by Tahirah Rasheed and Autumn Breon includes works from Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, Leila Weefur, Hank Willis Thomas, and Simone Leigh among many others opens to the public on January 21.

“Resting Our Eyes” is the first show Breon and Rasheed cocurated together, though it doesn't sound like it will be the last. The two got along quickly after being introduced, a long overdue meeting predated by many of their friends and colleagues encouraging them to speak. “[When] we started to get to know each other and realized that we both really identify with the tenets of Black feminist theory, that center and prioritize leisure, self-expression, and ideas like that. When we had the opportunity to curate an exhibition around ideas that are important to us, it organically came for us to center really trying to map out the visual vocabulary of leisure and adornment as it pertains to Black women,” Breon said.

Breon’s and Rasheed’s mutual respect and admiration was palpable during our conversation, with both citing the other as a source of inspiration for “Resting Our Eyes.” “I think that our approach is very Black feminist. It's not just the objects that we were choosing that were influenced by Black feminism, but also how we show up for each other, with each other, how we work together, the types of standards that we try to lead with, and approaches and practices. I think that was also very abolitionist and very Black feminists in nature, which makes sense. If we’re saying we're organizing towards this world and this is what we have organized our lives around, these nonnegotiables, it's not just in the objects that we choose and the work that we create, but how we work together, which is why I think it was so organic for us to work with each other,” Breon said.

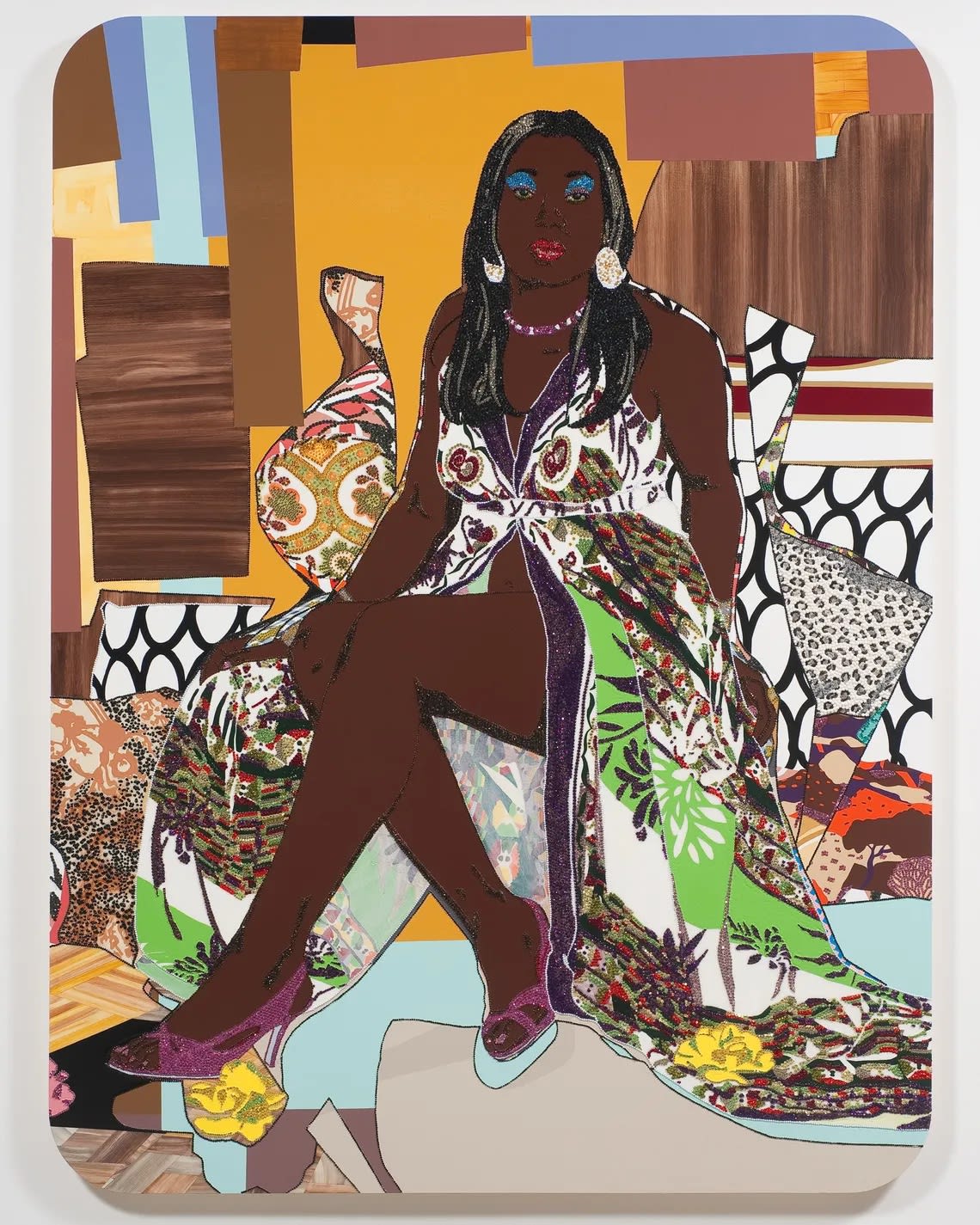

With self-inspiration and Black feminism as a foundation, Breon and Rasheed dove into thinking about which artists would carry the conversation forward. Mickalene Thomas “was one of the first artists that I thought of when we initially started talking about this idea,” Breon said. “The materials that she uses to adorn her work, how she works with acrylic and rhinestones. It reminded me of scenes of leisure, scenes of adornment that I’ve seen at my grandmother’s house, or how my aunts adorned themselves. It felt very familiar.”

Their exploration of lineage doesn’t stop here, with both Breon and Rasheed mentioning their aunts and mothers as inspiration. “An intergenerational lens is something that I innately have. Just seeing my grandmothers go to church in their church hats, and then that’s a part of how I practice everything that I do actually, how I see myself, how I adorn myself…. It’s how I grew up, it’s what I see, it’s what’s around me, it’s my history.” Rasheed said. This concept is apparent in the selection of artists included in the exhibition, which showcases a spectrum of creatives, young and old, like photographer Dr. Deborah Willis and her son, conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas

“Although each of us are making work informed by our unique experiences and perspectives, no one is making work in a vacuum. We have all been informed by a shared global experience, changing technology, a common awareness of art history, and our current political and social climate. It’s interesting to see how these commonalities become teased out by the curators of the show, and most importantly how the audience may see themselves within that narrative,” Helina Metaferia said.

Mickalene Thomas, Love’s Been Good to Me #2, 2010. Rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel, 96 x 72 in. Photo: Mickalene Thomas/ Collection of Jeffrey N Dauber and Marc A Levin.