Oscar Howe, the headliner of the exhibition Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe, was a bowler. As in, knocking pins over with a heavy ball, bowling. Oscar Howe was also a painter, known for colorful, swirling paintings that center his Očhéthi Šakówi (Sioux) heritage. Understandably, the exhibit now on view at the Portland Art Museum focuses on the latter rather than the former. Bowling is only mentioned once, and it’s in the catalog.

My latch onto the bowling detail could be explained by anxiety of influence in reviewing this show. Dakota Modern was reviewed by Peter Schjeldahl for The New Yorker when the show was at the National Museum of the American Indian. The review was published in July and Schjeldahl died in October. His eloquence will live on. In discussing Howe’s 1954 Dance of the Heyoka: “peekaboo are bits of figures in the plangent gallimaufry…Such paintings embody no rationale except their own.” Trying to write about this show has sent me into my own phlegmy spiral.

Thankfully, the installation of Dakota Modern in Portland is accompanied by a significant addition, Jeffrey Gibson’s They Come From Fire, that wasn’t part of the show in New York. The addition of Gibson’s work takes the Howe exhibit’s conclusions about the work and critical reception of a singular artist and applies them more broadly to comment on history, community, and individual experience.

Gibson’s project consists of installations on the exterior of the museum and in the Schnitzer Sculpture Court. The locations outside of the main galleries suggest a prelude or an introduction to Howe’s work. This makes sense logistically, but less sense thematically. Gibson made his work in response to exhibition curator and long-time friend Kathleen Ash-Milby’s work on Howe. The title They Come From Fire is taken from Howe’s 1965 painting He Came from Fire. Gibson’s work responds to Howe’s work and legacy more than introduces it. I’ll start with Gibson’s work and then tackle the Howe exhibition.

Suspended, multicolored glass panels dominate the space of the Schnitzer Sculpture Court. Gibson made the panels in collaboration with Portland-based glass studio, Bullseye Glass Co. Cursive script on each of the twelve rectangular panels proclaims different aphorisms – “They Choose Love,” or “They Protect the Land,” for example. All are freighted with meaning, but the one that speaks most directly to the project as a whole is “They rewrite their story.”

Spotlights trained on the glass panels project the glass panels’ multi-colored geometry onto the back wall, which is tiled with black-and-white photographs of people on the empty Park Block sculpture plinths. The photographs were pulled from a photo shoot that Gibson held last May when he invited Indigenouos, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and other community members to participate in his larger project vision.

Jeffrey Gibson, They Come From Fire (detail), 2022, site-specific installation, Portland Art Museum. Photo courtesy of Bullseye Glass Co.

The idea to use empty Park Block pedestals captured Gibson when he came to Portland for an initial site visit with Ash-Milby to determine the scope of the project. The plinths have been empty since 2020, when sculptures of Teddy Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, and The Promised Land were removed as part of the 2020 protests. Gibson’s photos give new life to the barren plinths, with a cast of individuals and groups, natal and chosen-family groupings. Some portraits came as no surprise given the venue and occasion: Carla Rossi, Lillian Pitt, and Sara Siestreem, for example. Others weren’t people I immediately recognized, but that, too, was part of Gibson’s project vision. A wall tag explains: “I want the overall work to point to narratives that may not be popularly known outside of these local communities and to celebrate the photographed individuals as leaders and innovators in the world today.”

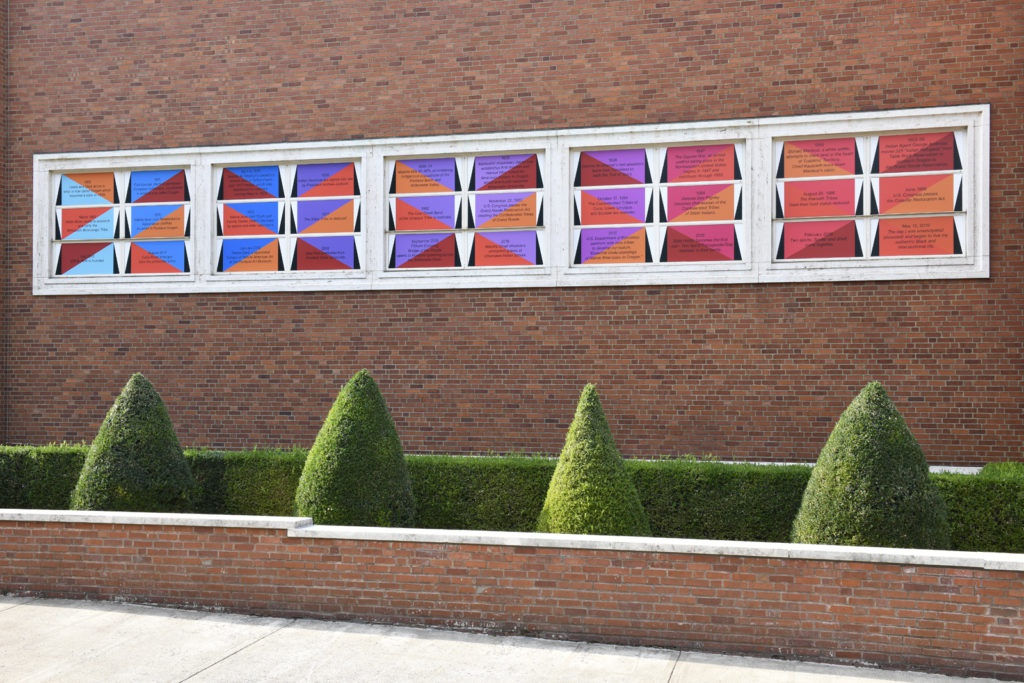

The notion of unsung narratives and their relationship to official historical record features in Gibson’s project on the exterior of the museum building as well. In multi-colored, triangle-patterned panels, Gibson intersperses the events that populate timelines (“1830 The Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson”) with other events, pivotal but not the kind that make the history books (“October 1998 Bill Ray marries Lawretta Ray”).

Jeffrey Gibson, TIMELINE, 2022, site-specific installation, Portland Art Museum. Photo by Dale Peterson.

Gibson’s work in the Schnitzer Sculpture Court is arresting and effective in its messaging. The exterior timeline, though strong in concept and theoretically well integrated with the ideas of the interior work, isn’t as impeccably executed. Some of the events – the marriages, divorces, births, moves – those seem in line with Gibson’s interest in celebrating individuals and their narratives. The importance given to the museum in the timeline though is curious, especially given the location of the work on the front of the museum. There are only sixty timeline entries. Including the founding of the Portland Art Museum (1892) makes perfect sense but to include the hiring of two PAM Curators of Native American Art, Deana Dartt (January 2012) and Kathleen Ash-Milby (July 1, 2019) as well as the hiring of Erin Grant as the “IMLS Curatorial & Community Partnerships Fellow” (February 2022) seems a bit much. The inauguration of Portland Art Museum’s collaboration with Numberz FM in 2019 is indeed noteworthy but including this and so many other events on this timeline almost ventures into the realm of self-congratulation.

Far more compelling than the institutional milestones are the personal ones: “1996 Gladys Bolton becomes Siletz’s Tribal Whipwoman and maintains this role for many years” or “1917 Lynette Howes’ grandparents move to Tammany, Idaho from the Cherokee reservation.” These entries augment the historical narrative, offering a welcome alternative to the “official” histories which have most often trained attention on events and people from dominant white culture at the expense of consideration of Indigenous, Black, or Queer histories. Equally, the textbook story of history has never considered most of the individual machinations that make up and shape life. The history textbook has always privileged the stories of the select few, in the United States, those designated as the “Founding Fathers” – the ones with the sculptures.

Jeffrey Gibson, They Come From Fire (detail), 2022, site-specific installation, Portland Art Museum. Photo by Dale Peterson.

Gibson didn’t remove Teddy Roosevelt or Abraham Lincoln from the Park Block plinths, but by asking Indigenous, Black, and Queer community members to occupy those spaces and putting the photographs up in the museum, he offers an alternative version of history–one that, instead of national heroes, celebrates real people for a history that is more representative of the collective, more inclusive, and more equitable.

The glass panel reads “They rewrite their story.” That statement conveys agency but doesn’t convey that it is a shared responsibility: Our collective story needs to be rewritten, because it is incomplete. In prioritizing a single story, it leaves most people out of that story. It’s as though standard history is a big rope composed of an infinite number of individual threads. Rewriting the story means untangling the rope and rearranging those threads into a web of meaning rather than only considering the pre-defined whole.