After Tirtzah Bassel became a mom, she noticed something strange about the Western art canon that she’d always loved so much. The act of birth was conspicuously missing. Fresh out of the maternity ward and hyperaware that being born is among the few things all humans have in common, Bassel found this to be a glaring omission.

“Like, if men gave birth, wouldn’t every single male artist have his depiction of birth that was a quasi–self-portrait? That’s obvious,” the New York–based painter told ARTnews. “What better metaphor do we have for the creative act? Clearly that metaphor did not serve men very well, and so it’s just completely absent. Men have worked really hard to create all sorts of other metaphors for creativity that centered a male experience.”

Bassel returned to her studio a few months later and started playing with the idea of an imaginary canon where the experiences of birthing and menstruating bodies ruled supreme (and the patriarchy never existed). In Bassel’s parallel universe—and in a series she calls “Canon in Drag,” art is made by women, for women, and commissioned by women.

She started with familiar images by Old Masters such as Rubens, Rembrandt, and Van Eyck. In Bassel’s version of the Crucifixion Diptych (1460) by Rogier van der Weyden, for example, a bloodied Christ is replaced by a menstruating martyr whose uterine wall sheds posthumously in a demonstration of possibility, loss, and renewal. The Origin of the World in Bassel’s canon resembles the infamous one by Gustave Courbet (1866), but as per its name, it shows the actual act of birth. (In the catalog accompanying the exhibition, a sort of alternate-universe art history textbook, the text for Origin of the World teases that this work “anticipated the 21st-century phenomena of birth as performance art.”) And in her remake of Petrus Christus’s The Nativity (ca. 1450), Joseph is no passive bystander but rather the primary caregiver of the baby Jesus, tenderly cradling him with skin-to-skin contact.

Bassel strays from the original artworks she transforms but never veers from the canon itself. “There’s an argument for ‘Let’s burn the whole thing down and start somewhere else,’ for obvious reasons,” Bassel admits. “I don’t want to throw it out; I just want it to expand. And the other thing is, for better and for worse, the canon holds such authority.”

In her adaptation of the canon, Bassel has created works that are utterly satisfying on their own. But she is not the first woman to appropriate iconic images by men to drive home a point about gender imbalances. Below are 11 other artists who have made canonical

artworks by men their own, across painting, photography, video, and sculpture.

Deborah Kass, 12 Red Barbras (the Jewish Jackie Series), 1993

In one of Deborah Kass’s best-known series, “The Warhol Project” (1992–2000), the artist uses the Pop artist’s celebrity portraits to address the lack of representation of Jewish people that she experienced growing up. “I had never seen a movie star that looked like Barbra [Streisand], which is to say that looked like me and everyone I knew,” Kass has said. Among the icons Kass granted the Warhol treatment are Streisand, Gertrude Stein (whom she turned into Chairman Ma as a wink to Warhol’s Chairman Mao), and Kass herself.

In 12 Red Barbras, 1993, Kass substitutes singer Barbra Streisand for Warhol’s repeating profile images of Jacqueline Kennedy. “I replace Andy’s male homosexual desire with my own specificity,” Kass explained. “Jew love, female voice, and blatant lesbian diva worship.”

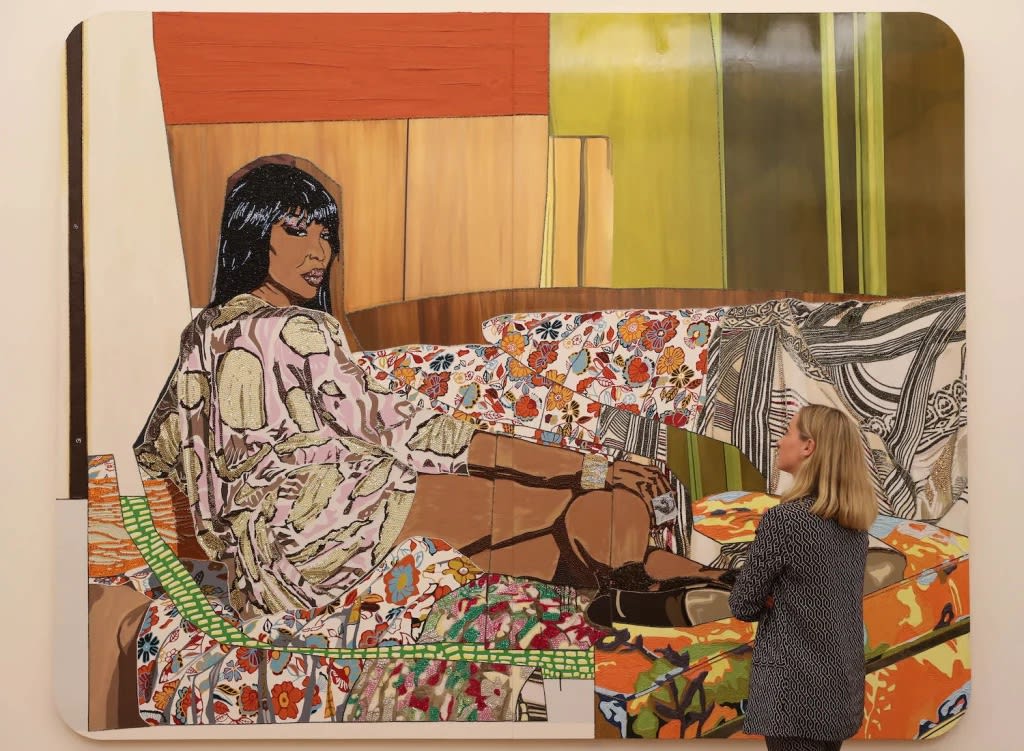

Mickalene Thomas, Naomni Looking Forward, 2013

Mickalene Thomas, Naomni Looking Forward, 2013, at Sotheby’s Frieze Week Contemporary Art Auctions, London, 27 September 2019.

In 2010 the Museum of Modern Art in New York asked Mickalene Thomas to create something for its 53rd Street restaurant windows. She came back with her own version of Manet’s landmark painting, Luncheon on the Grass (1862). In Thomas’s collaged photograph, not only is the commanding trio of Black women dressed (and exquisitely), but men don’t even have a seat at the picnic.

Thomas often references Western art history in her work, as in this painting of supermodel Naomi Campbell, which—like the Guerilla Girls piece above—quotes Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814). “By portraying real women with their own unique history, beauty, and background, I’m working to diversify the representations of Black women in art,” Thomas told Smithsonian magazine.

She has also revised the work of Manet’s contemporary, Gustave Courbet. In 2012 she reworked Courbet’s Origin of the World as Origins of the Universe I (2012), a painted self-portrait she created by photographing her own torso, abdomen and genitals and then transferring the image to canvas (using her signature rhinestones to stand for pubic hair and labial folds). The passive objectification that appears in the original painting became a powerful image of agency.