The underpass is a kaleidoscope of ever-shifting images, ideals, and codes

In 1994, a police officer passing through the Krog Street Tunnel caught sight of then 16-year-old Amir “Totem” Alighanbari with a spray paint can in hand. The officer started after Totem, who took off running before stopping to hide behind one of the tunnel’s pillars that separate the road and the sidewalk. Totem bounced between pillars like he was playing peek-a-boo with the officer, who eventually tired after a few minutes of chasing. The officer let Totem go, and Totem resumed his painting.

Totem, a Cabbagetown native, treated the tunnel connecting his neighborhood to Inman Park as his playground. The subway graffiti he saw after visiting family in New York inspired the teenager to try tagging, or stylistically writing, his name around his neighborhood in bold letters. Though graffiti-style writing could be seen in the tunnel as far back as 1967, Totem was one of the first Krog taggers to later launch a successful art career.

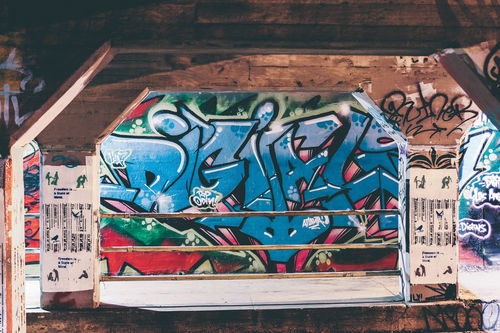

For a graffiti writer, the tunnel—a mishmash of graffiti art, tags, murals, and festival flyers—was the perfect canvas because the bridge provided cover and its concrete pillars framed the artwork. It served as a platform for young artists to prove themselves.

“At the time, I sought to emulate [graffiti artist] Hazus—he was the best in Atlanta all throughout the ’90s,” says Totem. “He didn’t like me, though, so I had to try to outdo him.”

As time went on, Totem and his friends Juis and Sevr went from tagging to painting more sophisticated murals and making their mark on a changing neighborhood. Cabbagetown was experiencing its first wave of gentrification, and abandoned warehouses like the Fulton Cotton Mill were being redeveloped. Totem says that the impulse to cover the tunnel with graffiti only grew as developments expanded.

“I had the attitude that, you might have bought my neighborhood, but that doesn’t mean I have to kiss your ass,” Totem says. “This was my neighborhood before you came, and we’re going to let you know this is our spot.”

In 1997, Totem spray-painted a portrait of “tough-guy” actor Robert Mitchum smoking a cigarette on the outer wall of the tunnel. The community responded favorably. Rather than whiting out the painting, they allowed it to remain untouched for more than 12 years. Later, at his brother’s urging, Totem started painting his phone number next to his portraits. The move led to commissions to paint murals for local businesses like Ria’s Bluebird, the former SciTrek museum, MJQ, and Liberty Tattoo. On Reynoldstown’s Seaboard Avenue, he created a mural that, 23 years later, still remains: a sprawling scene with yellow billowing clouds backdropping people in intricate grayscales.

Alabama native Michi Meko moved to Cabbagetown in 2003, just a few years out of college. He was enamored of the tunnel and the chrome letters of veteran Atlanta graffiti artist Baser. Meko approached him for artistic advice, but Baser instead shared the history of Atlanta graffiti and its unwritten rules.

“If your pieces could run for a long time in the tunnel, it affirmed your skill level,” Meko says, noting Totem’s Mitchum as one of the crown jewels. “It was a total game of respect, and I had to learn etiquette. If you wanted to cover up someone’s work, you had to be able to paint something that was better than what was there.”

Meko had a five-year run in the tunnel before realizing he could earn a living—legally—from his art. Under Georgia law, graffiti and even murals are considered a form of vandalism and remain illegal without a city permit.

“That was the usual trajectory: You start as a street writer and then find your way into different artistic fields. I chose the gallery route.” His street-writing style eventually morphed into murals and fine art that he now exhibits in contemporary art museums and galleries throughout the country. He’s currently in a traveling show called Dirty South, convened by Virginia Museum of Fine Arts curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, and the High Museum has an early work—a figurative piece that blurs the identity of men wearing saggy pants. His fine art still uses mark-making techniques and aerosols from his days in the tunnel.

Meko continues to live in Cabbagetown despite its changes, but claims the tunnel has lost its identity. “The tunnel now is full of ‘Sally Loves Johnny’ and ‘Atlanta United’ notes. You’ll see a piece go up and then boom, it’s covered by the next weekend like Nels’s F*ck Cancer piece, Meko says. “That meant something to people, so you should leave it alone.”

Peter Ferrari started painting in the Krog Street Tunnel around 2008 after graduating from Emory University. He learned about the graffiti legends who came before him, like Totem and Juis. Ferrari followed Totem’s example of bringing graffiti outside of the tunnel, and in 2011, he started painting commissioned murals, termed “street art,” for businesses like Hotel Indigo and Little’s Food Store in Cabbagetown.

In 2012, Ferrari started his own showcase, Forward Warrior, to legally paint bare walls of buildings in Atlanta neighborhoods.

“Commissioned murals have become really popular in Atlanta because people see a selling point for their business,” Ferrari says. “They’ll commission local artists to put up art because it makes them come across as authentic and being in tune with the local culture.”

Ferrari also helps curate murals along the BeltLine, choosing local artists to repaint its walls each year. “We now have an entire half a mile of commissioned murals right outside the tunnel that are respected,” Ferrari says. “Artists are allowed to spend much more time on the art, they get scaffolding, and they get paid.”

This newfound recognition and support didn’t come without a fight. In 2014, for example, when the Atlanta Foundation for Public Spaces planned a ticketed masquerade ball in the tunnel, nearly 100 artists, including Ferrari and Meko, organized a protest to paint the tunnel’s walls completely gray the week of the event to prevent the organization from profiting off the work of the artists. The protest left the Foundation scrambling for replacements in the days leading up to the ball.

Today, the murals and portraits of the late 1990s and early 2000s are few and far between, but the tags and stylized letters of the new generations are scattered all over the walls, as in Totem’s early days.

Totem hasn’t been back to the tunnel in nearly a decade and didn’t participate in the masquerade ball protest.

After several graffiti world tours, the husband and father now owns a studio in Norcross near Buford Highway, where he spray-paints artworks to display in exhibitions and restores vintage Japanese sports cars.

Though he calls himself an old wolf who is “long in the tooth,” he offers advice to the next generation of graffiti writers, cautioning against “whoring for dollars” in Atlanta’s expanding “ticketed art-for-pleasure landscape.” “The rule remains,” says Totem. “If you write over us, we’ll write over you.”