Poised and self-assured, James Little stands beside a pair of buckets, each filled with a different shade of black paint, in the Brooklyn studio where the artist has worked for three decades. The Memphis-born painter of absorbing abstractions—whether hallucinatory monochromes or variegated, potpourri-like surfaces—has been making all-black paintings for a decade, committing to each canvas for three or four months. In these works, contained geometries explode with nocturnal luminosity in concert with the viewer’s sways, and tightly orchestrated stripes play silent recitals of light, form, and movement. Little, who became an abstract painter after graduating from the Memphis Academy of Art in the early ’70s, has experienced what many would call a career breakthrough earlier this year with a majestic display of work in the Whitney Biennial; his current solo exhibition, Black Stars & White Paintings, is on view at Chicago’s Kavi Gupta gallery through December 20.

When I wasn't showing in the Biennial, I still always felt I was as good as anybody out there. Even when I wasn’t showing at all, I remained concentrated—focused on capturing the imagination of the wider public. Given where the art world is now, I’m definitely an outsider. Formalism was once the avant-garde, but no longer in this day and age. I am loyal to pure abstraction, and am not interested in painting a picture of anything. I’ve always looked at painting from the outside, by looking at other artists’ works and finding things that I wouldn’t do. I’ve always been concerned with the strength of a painting and try to make contemporary American art that can hold space on a wall next to a de Kooning or a Monet.

Most of the references that trigger my ideas are not in museums. Rather, they are outside, down the street where I might see a structure, a pattern, or a spill—stuff that people just don’t pay attention to. If it can fit within my vocabulary, then I’ll try it out. Everything is an experiment, including our democracy, and if we keep renovating it, it may survive.

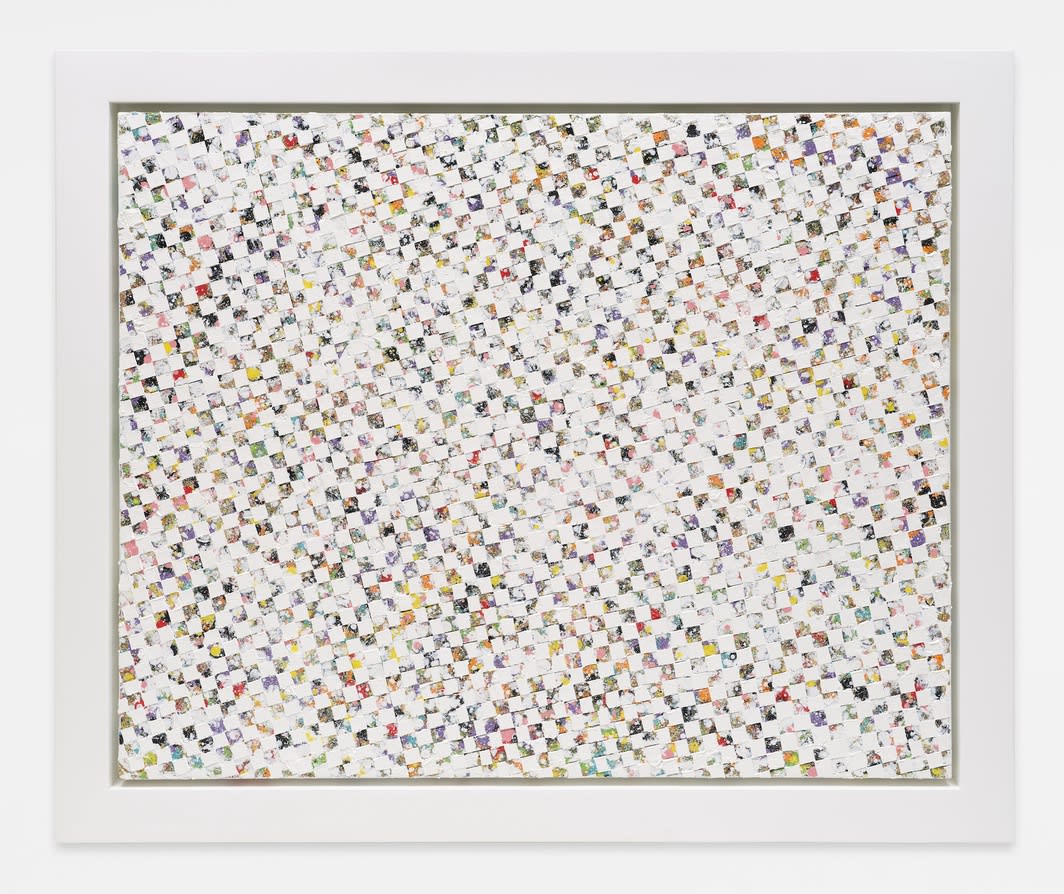

James Little, Thespian Stories, 2022. Oil on linen, 39 x 46 inches framed.

I am a political person but I don’t make political art. I try to make optimistic work and avoid too much verbiage or jargon. I am after something that can be shared with a wider community, rather than depending on a syllabus or descriptive analysis. You can say the paintings make social and political statements, but I try to stay away from identity politics. I can’t make a painting that reflects the terror and the pain inflicted upon people like me through racism. My experience has been shaped by living in the segregated Deep South, and if I were to paint that, it would necessarily be inadequate compared against that reality.

There is always a certain amount of fear: of the space; of the painting, of meeting the challenge at hand. I never want to lose the fear, because if I do, the only thing that replaces it is overconfidence. Before making an all-black painting, the surface is entirely white like a blank wall—there is nothing else, and that’s fear. There is possibility for both success and failure.

I wouldn’t say I work in isolation, but I like privacy and concentration. One reason for this is that I make a lot of my own paint, which has evolved over the years. The all-black paintings, for example, are a mixture of oil paint and beeswax, which I started using around 1972. For the white paintings, I still use oil because it feels necessary to use whatever medium that I think best reflects or expresses what I’m trying to do with the design and the format synergistically.

James Little, Spangled Star, 2022. Oil and wax on linen, 72 x 72 in.

When I paint the black-on-black paintings, the two separate shades can’t be too close to each other. Toward the end of the painting, however, I bring them really close, so you can barely see the difference. In a dark room, those paintings absorb whatever light there is. If you have more light, their response will be different—there is a subliminal, or even spiritual way in which they operate in a room. I’m interested in emotive content, in transcendence, and in physicality. There is an emblematic push-pull in the all-black paintings: By the time a third dimension appears, the work flips right back to the second dimension. I haven’t exhausted the ideas around a black painting—they are in a way measurements of time.

For each painting, I do various calculus iterations to figure out how big and complex the work can be. My mantra is to use what I need; if I don’t need it, then I won’t use it. I’ve been called a Minimalist, but I’m not—I just use what I need.

My intention is to eliminate predictability and not be repetitive. Music can be repetitive, but there is always change, chords, syncopation, rhythm. I try to accomplish something similar in my art, something that is more than a pattern or a set of regulations. I prefer to not have music playing while I’m working because painting with liquified wax is nothing to play around with. I love looking at each finished painting with music so I can actually focus and listen.

You have to constantly investigate and engage with the surface; the movement is perpetual—it won’t stop.

—As told to Osman Can Yerebakan