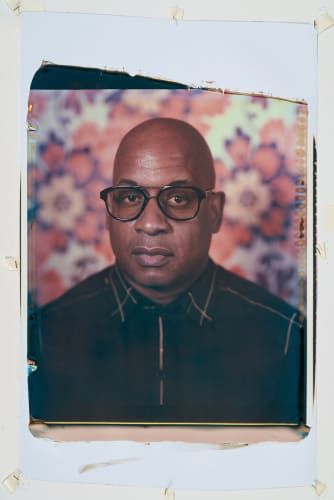

For over 30 years, the artist has been making work that speaks to American history — ambiguous, open-ended, existentially observant. At a time in which the fundamentals of fact and fiction are being questioned, his art captures the truth of a culture in decline.

On a wall in Glenn Ligon’s studio in Brooklyn, there is an astonishing 10-by-45-foot diptych bearing the entire text of James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village.” It is rendered in Ligon’s trademark style: painstakingly stenciled black-on-white letters partially covered with a layer of coal dust, which adds both weight and shimmer to Baldwin’s sentences. (“From all available evidence no Black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came,” the essay begins.) During a visit to the studio in May, the words “American soul” leap out. One strains to describe the impact of Ligon’s work in metaphoric language: His art provides its own language; it is its own metaphor. But the feeling he imparts is a kind of force field, asking us, as Baldwin did, where we stand, and where our bodies stand, in space and time, in relation to a history we share but, as a nation, upon which we do not agree.

This new painting is a culmination of a brilliant three-decade-long career — a bookend of sorts, as Ligon puts it. In 1996, he made his first “Stranger in the Village” painting, stenciling fragments of the essay on a gessoed canvas with oil stick, black on black: a visual play on Baldwin’s words, the blackness literally hard to read. (On the other side of Ligon’s studio is a black-on-black triptych of the complete text.) The essay, one of the writer’s most famous, recounts his experiences at age 27 in the hamlet of Leukerbad, where he had been staying with his Swiss boyfriend while finishing his first novel. “It did not occur to me — possibly because I am an American — that there could be people anywhere who had never seen a Negro,” he writes. The alienation Baldwin evokes is total, the simple racism of the village becoming a lens through which he sees with fresh clarity the more elaborated and systematized version of it back home.

“In the beginning, it was not only wanting to be with Baldwin but wanting to be Baldwin,” Ligon tells me when I ask how his relationship with the writer has changed over the years. “This intense identification with his queerness, with his Blackness, but also his engagement with what it means to live in America. In some ways it’s less about the specifics of the words, because I’d always taken his words and made them abstract.” Now that Ligon is 61 and one of the most celebrated artists of our time, he says it took him this long to be able to confront the text of “Stranger in the Village” in its entirety. “I’ve only used it in fragments for the last 20 years,” he says. “And maybe I feel like — calling Dr. Freud — this is a moment where I could tackle that in my work. The literal enormity of the text, in terms of its physical size but also its panoramic-ness, its breadth, its depth, you know?”

Ligon has in many ways inherited Baldwin’s mantle to become the foremost philosopher on race and identity in America. Like Baldwin, Ligon was making intersectional work long before it was commonplace outside of academia to think in such terms. (The Black law professor and theorist Kimberlé W. Crenshaw created the term “intersectionality” in 1989, the year before Ligon’s first solo show, to describe the ways in which our overlapping social identities, including our gender, caste, sexuality, race and other factors, influence our experience of the world and our position within it.) When Ligon made his first “Stranger in the Village” painting — on the other side of the civil rights movement from Baldwin’s original writing — he’d been creating paintings with stenciled fragments of text for several years; in 1989-90, when he had a PS 1 residency at the Clocktower Gallery in Lower Manhattan, he began covering the white-painted doors he found there with the words of Zora Neale Hurston (“I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background”), the repeated statements gradually dissolving into illegibility and opacity. The mantralike repetition evoked an entire psychology, an inner dialogue that blurred into a kind of fog of being. He confronted viewers unambiguously with what it meant to be a Black figure in white space, but more than that he seemed to unearth the unspoken consequences of the failure of human beings to read and know one other.

Looking at the work in Ligon’s studio, I wonder what Baldwin would have made of our current moment. There’s no question that we’ve become savvier about inequality, more aware of how our bodies are positioned in a hierarchy of value: our opportunities, cultural authority, health and finances contingent upon attributes over which we have no control. And yet, at the same time, the inequities defined by race and class have only intensified, and willful obfuscations have proliferated. As I write this, it’s the centenary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, during which mobs of white residents burned and looted what was then one of the country’s most prosperous Black communities, killing hundreds and displacing thousands — an incident still missing from most American history textbooks. The newspapers report daily the latest voter suppression law being enacted, or the newest effort to undermine teachers. It’s not that we haven’t learned anything from this past, exactly; it’s that, rather than setting a course for redress, the response is denial and outright delusion.

‘It sort of drives me crazy when people say, “Oh, the work is so timely,” ’ Ligon says. ‘Antiracism is always timely.’

Ligon’s art is often both an indictment and a kind of reframing of American history. He has worked across a wide range of media, in addition to writing the kind of criticism and curating the kinds of shows that revolutionize canons. He isn’t a painter of the human form, and yet bodies — desired, objectified, pathologized, policed and pitied — are central to all of his work. His 1988 “Untitled (I Am a Man),” often considered his first mature painting, was inspired by signs carried during the 1968 Memphis sanitation strike, when more than a thousand Black workers demanded higher wages and increased rights. Even this early piece suggests the elements that would become his signature: the visible painterly touch, the iconographic black on white, the reverberations of the past in our present. But at its core, the work’s central phrase — “I am a man” — is an anguished existential assertion. In this way, Ligon is obliquely present in many of his paintings, his identity filtered through mediated perceptions and narratives. For his 1993 show at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., titled “To Disembark,” Ligon was inspired by the story of Henry “Box” Brown, who in 1849 shipped himself from Richmond, Va., to Philadelphia in a bid for freedom, submitting his body to the terms of his objectification in order to escape. Ligon placed a set of wooden crates in a gallery and paired them with audio tracks, among them Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit,” her classic, haunting 1939 song about lynchings of Black people. The exhibition also included two print series, “Narratives” and “Runaways,” in which Ligon recreated period documents, more or less putting himself in Brown’s place. For “Runaways,” the artist enlisted friends to write descriptions of him as if he were a missing person and they were talking to the police: “Ran away, Glenn, a black male, 5'8". … Very articulate, seemingly well-educated, does not look at you straight in the eye when talking to you.” The more descriptions one reads, the more the personhood in question slips away, leaving a set of projections and abstractions.

Even when the human form is explicitly shown in his work, it serves as a mirror, a refraction of social takeaways rather than a single-pointed critique. This was the case in Ligon’s contribution to the 1993 Whitney Biennial, “Notes on the Margin of the ‘Black Book,’” an installation in which he framed pages from Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1986 book of eroticized photographs of Black men, sandwiching between them commentary from a host of sources, conservative and literary, foregrounding the various fears and fantasies projected onto these men’s bodies. (Among this commentary was a portion of Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village”: “… it is one of the ironies of Black-white relations that, by means of what the white man imagines the Black man to be, the Black man is enabled to know who the white man is.”) A watershed exhibition, the 1993 Whitney show was at the time reviled by much of the predominantly white and male critical establishment (the critic Robert Hughes called it “one big fiesta of whining”) — centered, as it was, on race, gender, sexuality and power. Ligon’s work, which spoke to all of these things at once, suggested the extent to which concerns over marginalized identities would shape art for years to come. When, in 1998, he made a clever double self-portrait, a pair of silk-screens on canvas, a homage to Adrian Piper’s iconic “Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features” (1981), he titled it “Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Black Features and Self-Portrait Exaggerating My White Features” — the joke, of course, being that the two photographic portraits were nearly identical.

In revisiting Ligon’s landmark works, I’m struck by his boldness — a quality he generally isn’t given credit for, perhaps due to his wariness of didacticism, skepticism of simple takeaways and preference for open questions, complexity and ambiguity. In Ligon’s appropriation of texts, I’ve thought I recognized a fellow introvert’s form of intimacy, a deep engagement with the words of forebears in the absence of actual mentors. But it also seems true that reframing the thoughts of others allows Ligon to express himself in a different register through the ventriloquism of art, as with Ligon’s work on Richard Pryor, whose voice he first heard as a teenager listening to the comedian’s albums on his cousins’ stereo. Brash and profane where Ligon is thoughtful and cool, Pryor inspired Ligon’s 2007 exhibition “No Room (Gold)” at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, which featured 36 gold canvases with Pryor quotes stenciled on them in black. (“No room for advancement,” Pryor jokes about the racism he has been subjected to. )

Ligon doesn’t shy from the fact that desire and objectification, power and sex are all a tangle. (In the 1993 version of “Notes on the Margin of the ‘Black Book,’” Ligon includes a personal exchange with his white boyfriend at the time, who confessed to having been asked if he was “into dark meat.”) Over the years, a question Ligon has been confronted with is whether he considers himself to be “a political artist” — a question that now seems preposterously naïve in its presumption of neutral ground. When I mention it, he chuckles. “When I first started showing in the ’90s,” he says, people would say, “‘Oh, your work is about your Black identity.’ And I was like, ‘That’s not a well that you just dip in and drink from.’”

Baldwin was always reminding us of the ways in which our moral lexicons are inseparable from our aesthetic ones. In one agonized passage in “Stranger in the Village,” he writes that even the most illiterate Swiss villagers have a claim on Western culture that he doesn’t. The inherited weight of an entire history of problematic representation is subtext to Ligon’s practice. Back in the late 1980s, he intuited the way semiotics — the academic study of symbols and what they signify, rooted in the human impulse to make meaning out of abstraction — might relate to racial prejudice, the way we essentialize people based on their skin color, as well as other characteristics. The inadequacy — and, often, outright manipulation and politicization — of public language and official narratives has a profound human cost. We all know what happens when phrases, events, even people become abstractions, reduced to signifiers, such as Ronald Reagan using the term “welfare queen” to rally his right-wing base, or the way in which critical race theory has become a straw man for a conversation many white politicians are afraid to have. As a young painter thinking about how to make the work he wanted without leaving too much of himself outside of the studio, Ligon found a mode of expression that exposed the tired binaries of abstraction versus figuration, of conceptual art versus painting, but also of the personal versus the political, as though these things haven’t always been complexly intertwined.

The centerpiece of Ligon’s 2011 retrospective at the Whitney, “Glenn Ligon: America,” was a 2009 neon work, “Rückenfigur,” in which the letters in the word “America” are reversed. The title, which refers to a pictorial device in which an artist includes a figure seen from behind, contemplating a landscape — a figure with which the spectator might identify — asks us to consider America itself as a makeshift construct, an unfinished argument. During the post-9/11 invasion of Iraq, Ligon saw a TV report of a teenage boy whose home had just been bombed by U.S. forces telling a reporter that America needed to live up to its promise. Ligon was struck by this. “America just bombed the [expletive] out of your city, but America’s still held up as this ideal,” he said.

Ligon has also discovered the downside of being a skilled semiotician in our virtue-signaling age, finding his work posted on Instagram by historically white institutions in facile displays of racial awareness. After the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art was criticized for posting an image of one of Ligon’s works, “We’re Black and Strong (I)” (1996), a silk-screen painting depicting the crowd at the Washington Mall during the Million Man March in 1995. The museum later posted an apology after comments pointed out the moral laziness of an institution leaning on a Black artist for commentary rather than issuing a statement of its own. A few days later, after Max Hollein, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used an image of one of Ligon’s 1992 etchings featuring text from Hurston in a letter to the museum’s members, Ligon himself spoke up on his Instagram feed: “I know it’s #nationalreachouttoblackfolksweek but could y’all just stop. … Or ask me first?” (The Met later apologized.)

Such digital-age exploitations point to a longer history of American art institutions’ superficial engagement with Black art. The idea of these institutions only paying attention to Black artists in moments of trauma or anger is all too familiar to Ligon, who knows what it means to be the token artist of color at the fund-raising dinner, or to be grouped in shows in which only artists of color appear, as though art made by African American artists were somehow on a different shelf, or relevant only during Black History Month or after the latest atrocity. “It sort of drives me crazy when people say, ‘Oh, the work is so timely,’” says Ligon. “Antiracism is always timely. Or, ‘Well, you have to excuse that because he was a man of his time.’ I’m like, ‘So was Frederick Douglass.’ I mean, Trump, he’s a man of his time, too.’”

Ligon’s curatorial work has pointedly underlined the call and response across art history’s exclusionary and arbitrary barriers. For his 2015 show at Nottingham Contemporary in England, “Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions,” he contextualized his own work within that of a range of other artists with whom he has found affinities, both elders (David Hammons, Jasper Johns) and contemporaries (Cady Noland, Kelley Walker). In 2017, at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, he used a 2001 Ellsworth Kelly wall sculpture originally commissioned for the foundation, “Blue Black,” consisting of two painted aluminum panels, as a jumping-off point for a show full of intriguing juxtapositions: A cluster of portraits, including a 1963 silk-screen painting of Elizabeth Taylor by Andy Warhol and Lyle Ashton Harris’s 2002 blue-tinted photograph of himself dressed up as Billie Holiday, became a conversation across time about who appears where and how. Ligon positioned his own 2015 neon work “A Small Band,” which reads “blues/blood/bruise,” the words taken from the testimony of a Black New York teenager savagely beaten by police in the 1960s, so that one could see the Kelly sculpture’s blue and black through it. When I ask Ligon how he decides, in history’s vast panorama, where to turn his attention, he’s silent for a moment, considering. “That’s an interesting question,” he says, explaining that he sometimes feels as though he has a kind of “chronological dyslexia” because of the way in which history can feel so present tense. “I guess I remember things that are attached to an emotion,” he concludes.

It’s tempting, for the critic seeking autobiographical through lines, to create a portrait of the artist as a stranger in the village, making his way among highly insular schools and institutions to became a leading artist of his generation. And in fact, that’s all true, if obviously reductive. Ligon’s story began, fittingly, with letters on a page: an alphabet exercise he made short work of as a bright kindergartner in the South Bronx. “The next day, my mother got a call from the principal at the school asking her to come in for a conference to talk about the fate of her children,” Ligon says. (His older brother, Tyrone, was also gifted.) Ligon’s mother was a nurse’s aide at the Bronx Psychiatric Center and was separated from his father, who worked for General Motors. “She couldn’t afford private school,” Ligon explained. “But she said that during the conference, one of my homeroom teachers said to her, ‘Well, your kids might be smart here but in a real school they would probably just be average.’” “Here” was a public school in what was then the poorest congressional district in the nation. But it’s also where, as Ligon points out, the Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the former Secretary of State Colin Powell and the urban planner Majora Carter grew up. He was once asked in an interview what it was like to have grown up “in a cultural desert,” and Ligon laughed. “I said, ‘Ever heard of hip-hop?’”

In calling around, Ligon’s mother found the ultraliberal Walden School on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, which was eager to diversify its student body. On field trips, Ligon went to SoHo, where he saw Andy Warhol’s paintings and ate brown rice and tahini for the first time at Food, the restaurant founded by artists including Gordon Matta-Clark. His mother didn’t want him to become an artist — “We didn’t know any artists” — but his talent was apparent, and she sent him to after-school programs in ceramics and drawing. Everything in these years was an influence on him, from Grandmaster Flash playing D.J. sets in the parking lot downstairs from the family apartment to the elaborate lettering of the graffitied subway cars he rode to school. While his older brother was athletic and gregarious, Ligon was bookish and shy (he identified with Spock on “Star Trek”); most of his friends lived over an hour away by train or bus. When his mother made them go outside to play, he would take the elevator to the first floor — they lived on the 11th — and wait in front of the maintenance workers’ office, where there was a clock. “I would sit in front of that clock for an hour and then go back upstairs,” he says.

At around 14, he found himself entranced by his uncle Donald’s white vinyl boots. “White vinyl was the frontier of masculinity,” he writes in an essay included in his 2011 collection of selected writings, “Yourself in the World.” “It signaled that the wearer was unconcerned with trivialities such as gender and sexuality, that he had reached higher ground.” After persuading his mother to buy him a pair, he found the effect not quite as he’d wished. (He’s since found his style: On the day we spend together, he wears a crisp navy Comme des Garçons shirt, picked out by Luca, the 7-year-old son of the gallerist he used to show with in Japan, and large glasses that strike me as the perfect framing device for his face, imparting both gravity and irony in equal amounts.)

Books opened another realm of possibility. When we meet, Ligon is reading Frank B. Wilderson III’s “Afropessimism” (2020) and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s “The Mushroom at the End of the World” (2015), but he started out with the books and set of Encyclopaedia Britannica his mother kept on the shelf. (While giving me a tour of his studio, Ligon points out that small wooden bookshelf, which now sits in a studylike area and is filled with an assortment of items: a sage bundle, books on Pier Paolo Pasolini and Cy Twombly, a drawing by Luca and an etching by Goya.) In high school, one of his English teachers held an after-school poetry workshop at his home in the West Village, on Christopher and Bleecker Streets. Downtown, Ligon discovered writers like Audre Lorde and Octavia Butler at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, the first gay and lesbian bookstore in New York; he remembers hearing Lydia Lunch and Exene Cervenka performing spoken-word poetry. He liked the punk band X (Cervenka was one of the vocalists), but also the Pointer Sisters; Joni Mitchell, but also the Sex Pistols and John Coltrane, and this stylistic range would help inform his later appropriations.

It was while studying at Wesleyan University that he first read Hurston and Baldwin seriously, in Robert O’Meally’s African American literature course. O’Meally, a scholar of the Harlem Renaissance, invited Ligon, whom he knew was an art major, to a lecture by the painter Romare Bearden at Yale. “We’re waiting for the lecture to start and this guy comes out wearing coveralls and stuff and starts adjusting the microphone, and I’m still looking for Bearden,” Ligon says. “And then I realized, ‘Oh, that is Bearden.’ But later on, I thought, ‘I have so little imagination about what a Black artist looks like that even when they walk to the podium, I can’t imagine it because they just didn’t exist for me.’ … So, yeah, it was interesting, that lack of imagination about the thing that I was starting to want to be, but I had no role models for it.”

In time, Ligon himself would become an essential generational link connecting the Black abstractionists of the 1960s and ’70s to the art being made now, but when he was still an artist in formation, people like Norman Lewis and Beauford Delaney — Modernist painters who challenged us to think less rigidly about modes of visual representation — weren’t even part of the conversation. When I tell Ligon I share his fascination with Delaney, a gay bohemian who, like his friend Baldwin, found a certain sense of liberation in Paris, Ligon shows me a haunting watercolor by the artist hanging in his studio; painted on a trip to the South of France that Delaney took with Baldwin, it shows an abstracted figure on a beach, the sea a band of blue sandwiched between the glowing yellow sand and sky. The catalog for a 2020 exhibition devoted to Delaney and Baldwin’s relationship at the Knoxville Museum of Art included two personal letters of tribute from Ligon to Delaney, who died in 1979: “In your paintings, the line between figuration and abstraction is always porous. That has inspired a similar fluidity in my paintings, which often turn text (a kind of figuration, I suppose) toward abstraction.” I sense that the influence might also be spiritual, rather than strictly aesthetic: a queer Black predecessor who was unflinching in the way he saw the world, an intensity matched by few painters of his time. Ligon agrees, explaining that he’s also moved by the painter’s friendship with Baldwin, who was only 15 when he found a kind of role model in the older artist. As Delaney’s mental health began to deteriorate in the 1960s, Baldwin became the steadying hand that allowed Delaney to keep turning out remarkable light-filled paintings. I can’t help but wonder how Ligon’s work might have evolved differently had he had someone like Delaney in his life.

In an interview with the artist Byron Kim for the catalog of the 1998 show “Glenn Ligon: Unbecoming” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, Ligon said, “I had a crisis of sorts when I realized there was too much of a gap between what I wanted to say and the means I had to say it with.” At the time — the mid-1980s — Ligon was a student at the Whitney Independent Study Program, the museum’s prestigious curriculum in arts education, where he lasted one semester before, he says, he was asked not to come back. Conceptual work was at the forefront, much of it using appropriated imagery or text: Barbara Kruger, Martha Rosler and Yvonne Rainer all taught at the Whitney ISP. Meanwhile, downtown, the famous painters of the time, including David Salle and Julian Schnabel, were operating in a very different mode from the Abstract Expressionism Ligon loved. He had to reach back a bit further to find what he needed: Jasper Johns’s stenciled letter and number paintings, Philip Guston’s swivel from abstraction to figuration and Cy Twombly’s lyrical graphomania. (It seems not coincidental that Ligon was also working as a legal proofreader at the time.)

While at the ISP, he began overlaying text appropriated from porn magazines over beautifully painted canvases. One 1985 work reads, “I don’t really know what happened. I mean, I’m not gay or anything. It was a fluke. Yes, that’s it. It just happened. I’m sure it’ll never happen again.” It was, he thinks, the last time he used his own handwriting in his work. “Even though I was really into Twombly, I didn’t have that kind of beautiful graphic line that he has. And also, I was quoting,” he says, adding that his own handwriting “seemed too personal.” At the time, he was sharing a tiny studio with another student, a woman who was working on a project about the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot and hysteria: “I was saying, ‘Ugh, the reading’s so difficult for me because I just didn’t take theory courses in college. I’ve been reading James Baldwin essays as a palette cleanser,’ and she’s like, ‘James Baldwin, who’s that?’ And I thought, ‘The problem is not that you’ve never read James Baldwin, the problem is you’ve never heard the name.’ Which was indicative, I think, of a certain kind of way of being in that milieu at that time. You had to toe the party line. And maybe that was the beginning of me thinking, ‘OK, I’m putting Baldwin in my work. I’m putting Hurston in my work. If you don’t know, now you know, because it’s in the work.’”

Ligon’s mother wasn’t alive to see his first solo show, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me: A Project by Glenn Ligon” in 1990 at BACA Downtown in Brooklyn, though he remembers taking her to an open house at the Whitney ISP of mostly conceptual art that included his porn texts. During the opening, held in a walk-up loft on lower Broadway, the power went out. “So no wonder she was like, ‘Why do you want to be an artist? Some crazy walk-up loft that goes dark in the middle of the opening, is this what being an artist is?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, it kind of is,’” Ligon says with a laugh. He clearly has empathy for the woman who gave him the very opportunities that made it harder for her to understand him. When I ask about his father, who lived nearby, Ligon shows me the “Dream Book” series he did in the late 1980s. Ligon’s father, who died in 2002, worked at General Motors’ Tarrytown, N.Y., plant; on the weekends, he ran numbers at the local pizza parlor. “Everybody played the numbers; it was illegal, but it wasn’t considered strange,” Ligon says. Like many people, his mother kept a dream book (hers was next to the encyclopedias); when you had a dream, you could look up what appeared in it and use the corresponding number to play the Lotto.

One day, Ligon’s father — agitated, suffering from hypertension, lying in a hospital bed after a heart attack — told him he owed someone named Dizzy money. “I was like, ‘OK, Dizzy — how much you owe him?’ ‘Three hundred bucks.’ ‘OK, well, I’ll go pay Dizzy.’ ‘He’s at the club’” — a Bronx pizza parlor that was a front for illegal gambling — Ligon recalls. “I lived in Brooklyn, so I was like, ‘OK, I’ll go on a weekend to pay Dizzy.’ ‘No, you got to go sooner. Interest compounds daily.’” Ligon found Dizzy outside the pizza parlor behind the wheel of a Cadillac. He had three missing fingers: “Not a very good loan shark,” Ligon thought. “And he’s like, ‘How’s your dad? I got to go visit him while he’s in the hospital.’ I’m like, ‘Please don’t go see my dad in the hospital.’ It turned out they were old buddies from the G.M. plant; he was at my parents’ wedding. Loan sharking was just the side life. He lost his fingers in an accident at the plant. They were friends.”

In other words, no one’s story is simple. The personal histories we tell, in all their ambiguity, have a way of becoming emblematic, worry beads that allow us to hold on to people we never fully understood and who maybe never really understood us. His father was a hardworking man who never missed a day at the plant before the heart attack, Ligon says; he had a second family after Ligon and his brother, and presumably, he needed the money. It’s also a story about friendship, something Ligon takes seriously; he keeps a tight circle of friends, including Kim and the artist Gregg Bordowitz. It was Kim who introduced him to his current partner, James Hoff, a multimedia artist and an art-book publisher. They met at “the last supper,” as Ligon puts it, before the pandemic’s onset. Hoff visited him shortly thereafter in upstate New York, where Ligon, who also has an apartment in Lower Manhattan, has had a home for a decade or so. “We talked for like seven hours in my backyard and I thought, ‘Well, that’s a good sign, since I don’t know you at all.’” When it got late, Ligon offered Hoff the guest room — a courtly gesture that has subsequently become the amusing centerpiece of their origin story. “And he’s like, ‘F this, I’m going home.’ But we worked it out. It worked.”

Some things, the best things, can’t be planned, but they require a certain kind of person to recognize the moment. Many of Ligon’s breakthroughs have come by accident. In his ongoing series “Debris Field,” which he worked on both before and during the pandemic (the newest will appear in a show at Hauser & Wirth in New York in November), allowing for error has taken him in a new direction: This time, stenciled letters don’t form words but are sent floating on their own, bodies in space, the paint allowed to bleed beyond the margins of the stencils. When he was making his first text paintings in the late 1980s, he was trying to make the text very clear and clean and flawlessly justified; it took him about six months, he says, to see the potential in the mistakes. These moments, Ligon says, are crucial: “You can’t plan those things. The mistake was the fact that the text was getting all smeary until I realized, ‘Oh, smeary text is the thing.’” His use of black neon came about in a similar fashion: One day in 2007, Ligon met Matt Dilling, a neon fabricator whose shop was in the same building as Ligon’s studio. Dilling showed him the project he was working on — white neon tubing with black paint on the front for a Burberry window — “and I was like, ‘Negro Sunshine,’” he says, snapping his fingers, instantly envisioning the phrase from Gertrude Stein’s 1909 novel “Three Lives” rendered in the same way. He commissioned it on the spot, and it became one of his most recognizable pieces. “I decided to include it in a show before I’d even see it, which was weird,” he says. “But I just knew it was going to be good.”

Late in the afternoon, we leave Ligon’s studio and visit “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” the New Museum show that he, along with Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni and Mark Nash, took over curating when its originator, Okwui Enwezor, died of cancer in 2019. Enwezor had conceived of the show as a showcase of Black art in the context of the white grievance unleashed and normalized following the 2016 U.S. election. Describing the last time he saw the eminent curator, who was undergoing chemotherapy in a Munich hospital as they discussed the exhibition, Ligon chokes up. Pulling the show off in Enwezor’s absence, with all kinds of public health restrictions in place, was a challenge. “I mean, I have said that I make work to think about things — well, I curate shows to think about things, too,” he says. “And so when I’m curating a project, I feel some responsibility toward the art, the artists I’m working with, you know, not to do them wrong. … Toni Morrison says you’ve got to write the novels you want to read. So you kind of have to curate the shows you want to see.”

“Grief and Grievance” displays the many ways Ligon’s contemporaries, predecessors and inheritors have embodied white spaces, from “Peace Keeper,” Nari Ward’s surreally menacing 1995 installation, recreated in 2020, of a tarred-and-peacock-feathered hearse, to Melvin Edwards’s “Lynch Fragments,” a series of brutalist clusters of welded steel scraps the sculptor began in the 1960s. (Bumping into Edwards and his family at the museum, Ligon pauses to thank the sculptor for his contribution.) Ligon’s neon work “A Small Band,” with its “blues/blood/bruise” affixed to the museum’s facade, sets the show’s tone. Ligon points out Jack Whitten’s 1964 work “Birmingham,” which I’ve never seen in person: a 16-by-16-inch square of plywood covered with blackened aluminum foil torn and peeled back to reveal an image that takes a moment to coalesce: It’s a newspaper photograph of a police dog attacking a civil rights marcher.

As we stand together in one of the gallery’s dark screening rooms watching Garrett Bradley’s 2017 short black-and-white film, “Alone,” about the toll of incarceration on a young woman, Aloné Watts, whose partner is in jail, I think of the way in which the histories we write, document and live are all with us: Ligon’s “chronological dyslexia.” As the camera lingers on Watts — she’s alone in bed, lost in reflection and longing — I’m reminded that damage continues apace. There’s no doubt we’re trapped in history, as Baldwin wrote, and that history is trapped in us; but the strength of any village is relational, and those who know its periphery tend to be those who see it most clearly.