Mr. Little waited more than 40 years to show his work in the Whitney Biennial. This year, he prepares for two gallery shows and a collaboration with Duke Ellington’s music.

James Little was just 28 back in 1980 when he sent reproductions of his abstract paintings to the Whitney curator Barbara Haskell in hopes of being selected for the biennial she was organizing.

Having moved to New York four years earlier after completing his M.F.A. at Syracuse University, the Memphis-born artist had just been included in Afro-American Abstraction at PS1 in Queens alongside Ed Clark, Sam Gilliam, Al Loving and Jack Whitten, among others.

The well-reviewed exhibition gave Mr. Little reason to believe that the art world might finally pay attention to him and his peers who were rejecting the expectation of Black artists to make figurative and identity-based work.

Ms. Haskell praised Mr. Little’s paintings in a gracious letter that he said he has valued all these years for the encouragement and acknowledgment it offered. But she didn’t put him in the biennial. He would have to wait more than four decades.

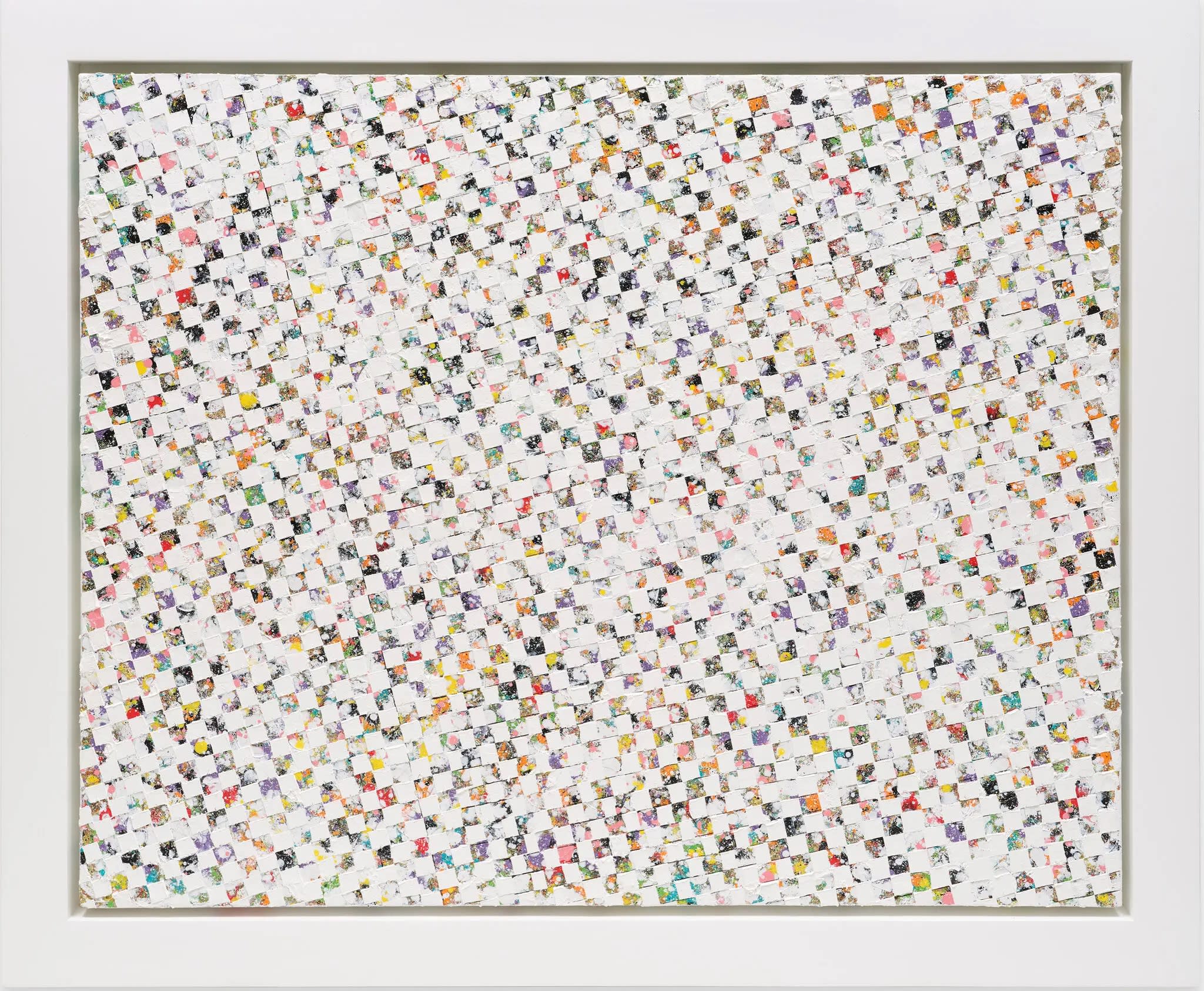

Mr. Little’s piece Thespian Stories (2022) was created on linen. Each colorful square contains a multitude of swirling pigments, applied with eye droppers. After more than four decades, he has stayed true to his labor-intensive approach to abstraction.

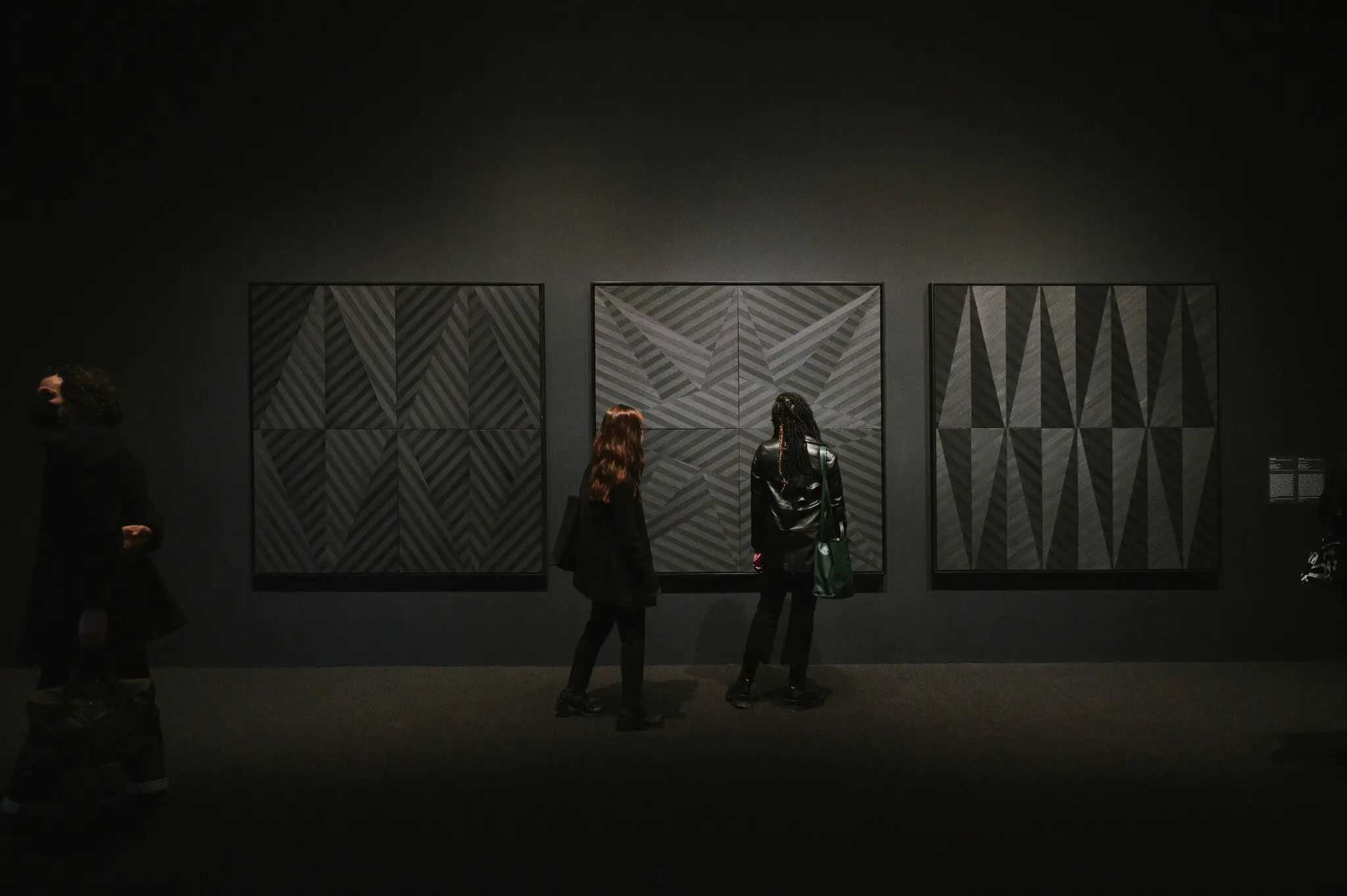

Today, at 70, Mr. Little is widely heralded as one of the breakout stars of this year’s Whitney Biennial. The museum has just acquired his large-scale oil-and-wax canvas Stars and Stripes (2021) — which Holland Cotter called “magisterial” in his review in The New York Times. Painted with colliding diagonal bands in two shades of black that optically shift between lighter and darker with the viewer’s movement, the dynamic canvas was one of three such geometrically patterned all-black works by Mr. Little in the show that held court with a mysterious luminosity and presence.

At his longtime studio on Hope Street in Williamsburg, the artist said that working outside the limelight allowed him to find his voice and personalize his art. “I knew the recognition was going to happen sooner or later,” said Mr. Little, who has stayed true to his labor-intensive approach to abstraction emphasizing color, design and structure. “I’ve always been in the mix.”

Mr. Little was preparing for his first show with the Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago, opening Nov. 12, called Black Stars & White Paintings. It will include more of his two-tone black paintings, a theme he has explored in variation over the last decade. He spends three months on each piece, painstakingly building their intersecting vectors in up to 20 layers of hand-blended pigments that he mixes with hot beeswax to seal the color and give it a kind of sheen.

His longtime studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where Mr. Little said that working outside the limelight all this time allowed him to find his voice and personalize his art. Elias Williams for The New York Times.

“I come from a family of construction workers who used to mix mortar and lay bricks,” he said. “That had an effect on me.” So did his mother’s cooking from scratch and structuring of meals for seven children. Indeed, his studio tabletops looked like a kitchen explosion or a mad scientist’s lab with a jumble of buckets, jars, bottles and blenders filled with his concoctions. On the canvases, though, all is distilled and clean-edged, bridging vernacular craftsmanship with modernist ideas mined from Paul Cézanne, Piet Mondrian and Willem de Kooning, among others.

The Gupta exhibition will also show Mr. Little’s more recent series of white canvases, some included at the Whitney, that are studded with grids of little circles or rectangles, each containing a multitude of swirling colors like mini Jackson Pollocks. These grids are inspired by commonplace industrial design that the artist notices on architecture, sidewalks and textiles.

“The whole society’s full of patterns,” said Mr. Little. He uses up to 100 different shades of color applied with eye droppers to the surface of these canvases. Then he masks off a grid of repeating shapes and pours white pigment over the entire piece, lifting the shapes when the upper layer dries. He never knows exactly what will be revealed in the resulting apertures.

Krista Schlueter for The New York Times

“Each one of these is like a universe in its own,” said Mr. Little, who’s always interested in imbuing his work with a certain optimism. “How can I make it musical? How can I make it playful and joyful? It harks back to Christmas toys and celebrations.” He’s experimenting with smaller versions of these white grids on oval canvases, set in diamond-shaped frames, for his first show next spring with Petzel Gallery in New York that is now representing him as well.

With a deep affinity for music, particularly the improvisation of jazz, Mr. Little is collaborating with the New York Choral Society on the presentation of Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts on Nov. 18 and 19 at The New School.

“James’s compositions have this rhythm and precision that reminds me of a musical score,” said Patrick Owens, the choral society’s executive director who knew Mr. Little’s work from his years showing at the June Kelly Gallery.

Mr. Owens invited the artist to use a huge projection screen behind some 120 vocalists and a 60-person orchestra that will perform movements of jazz, choral, gospel and symphonic music taken from Ellington’s three Sacred Concerts, ecumenical reflections on personal faith that were originally performed between 1965 and 1973. Mr. Little is sitting in on rehearsals, selecting more than two dozen paintings from across his career to project on the screen in conversation with the music.

“Painting is a solo act — I try to put the orchestra together pictorially,” said Mr. Little, who is embracing this first opportunity for artistic collaboration.

During the civil rights movement, many African Americans wanted Ellington to be more forthcoming, said Mr. Owens, but “he was very dedicated to his music as a force as opposed to actual protest.” Similarly, Mr. Little, who grew up in the very segregated environment of Memphis and was 16 when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated there, has committed to abstraction as “the best expression of my free will,” he said, despite pushback over the years from some for not engaging in social issues.

Adrienne Edwards, co-curator of the Whitney Biennial this year who was pointed toward Mr. Little by the artist David Hammons, called Mr. Little’s work “unapologetically minimalist,” adding: “It’s artists like him who are often overlooked because people tend toward sound bites or things that affirm their own beliefs.”

Charlie Rubin for The New York Times.

She was drawn to the soulfulness of Mr. Little’s work and his relationship to labor — “how ordinary things like bricklaying could be a space of imagination for him,” she said. Installed amid a cacophony of politically charged works in the biennial, Mr. Little’s black monochromes with two contrasting tones anchored a dark room with “ice-cold lighting that really allowed the blacks to dance on those black walls,” Ms. Edwards said. “They did a lot of work for us in that installation. There was a solemnness and space of reflection even in the chaos.”

Valerie Cassel Oliver, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, was struck by the ambience of Mr. Little’s black stars in that dark space. “One thinks of black paint as the absorption of light, but it’s just very much alive in his hands,” said Ms. Oliver, who has included a large painting by Mr. Little with polychrome stripes and zigzags in her traveling exhibition The Dirty South, on view now at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

Mr. Little’s black paintings “take Frank Stella to a whole different level,” she continued, referring to the older artist’s minimalist black monochromes from the late 1950s that were seen as groundbreaking. “James is carving a little niche for himself within that very long trajectory in the history of art. It’s familiar and yet it’s new territory. It extends what we understand as American modernism.”