- X

- Tumblr

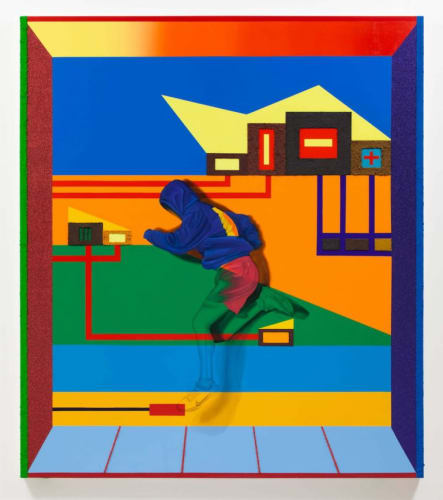

In 2019 I was introduced to Jamaal Peterman at his Pratt graduate thesis exhibition “The Greenbelt.”

Immediately, I asked about the title, rightly assuming it was a reference to the Prince George’s County, Maryland neighborhood. Having recently moved from Washington, D.C. to Brooklyn, New York, the works’ motifs caught my eye and reflected the changing landscape of both cities.

I saw the changes as a reflection of cultural and population shifts that have been informed by systemic inequities and access to capital and property ownership.

In Peterman’s works, the often-separated suburbs and cities are placed in relation. Thinking about the current state of D.C.’s Black population, one cannot help but consider Prince George’s County’s role.

The D.C. Black middle class’s exodus to Prince George’s County between the 1980s and 2000s left the city’s housing market and Black population vulnerable to corporate interests.

Peterman’s work focuses on the history of space both systemically informed and personally perused. In the era of diversity and inclusion, he adds nuance to many conversations about how Black life compares to that of other races. While systemic challenges inform Peterman’s work, they remain peripheral to the “in-house” discussions led by us and about us.

Jamaal and I spoke briefly about his recent exhibition and explored his practice and personal principles.

MG: Jamaal, I was introduced to your work with the Greenbelt series, referencing your childhood neighborhood of Greenbelt, Maryland. Can you describe Prince George’s, “P.G.” County for those who are not familiar?

JP: Prince Georges County is the richest Black county in America. It’s home to a subculture of music from Go-Go to house party music. The DMV is an acronym for D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. We use this term when describing Prince George’s County, and its abundance of multi-layered communities at various class levels of Black excellence. When using this reference, we talk about the entire scope of Maryland, not just the county.

MG: How does P.G. County inform your work? Is it a starting point, or do you think it will be a constant reference, even if implied?

JP: My practice is heavily informed by my environment. In Prince George’s County’s landscape, I have learned to value my self-identity, and cherish my community while seeing an abundance of economic growth. I have also seen the hardship and turmoil that have turned the most beautiful communities into the darkest neighborhoods. My life has been molded in the DMV, but it doesn’t define my outlook on progression. In my practice, I choose to record history as I see it. Not just my history, but also art history. I challenge myself and my practice to confront macro and micro relationships of class, sex, race, and gender. The DMV is a starting point for my viewers to know where I grew up, and the beginning of my ideology of African-American culture and a hierarchy system.

MG: I saw your recent exhibition at James Fuentes’ “Grunch in Bed.” May you connect the show to its title reference R. Buckminster Fuller’s Grunch of Giants (1983). What elements of the book are central to this body of work?

JP: The title of the exhibition refers to R. Buckminster Fuller’s allegorical final book, Grunch of Giants (1983), in which he argues that humanity would bA CONVERSATION BETWEEN JAMAAL PETERMAN AND MALEKE GLEE.e better off imagining its future beyond the unsustainable limitations and domination of the Gross Universal Cash Heist (GRUNCH) that we find ourselves within. With Grunch in Bed, I not only encode and decode the invisible forces that reproduce the landscape of our world; but also present alternative visions of this landscape by simultaneously interrupting and taking hold of the fundamental concepts of structure, visibility, information, flow, and time that the body must move through in order to transform it.

MG: What are you currently reading or researching as connected to your practice?

JP: I’m currently reading, “The New Great Depression: Winner and Losers in a Post-Pandemic World” by James Rickards. In fact, before I read James Rickards The New Great Depression, I read another one of his earlier books Aftermath which pushed me to read R. Buckminster Fuller’s allegorical final book, Grunch of Giants (1983). In my practice, I research a lot about economic growth and development. In doing so, I can easily break down the environment and its landscape all while understanding the impact it has on the Black and brown community. I have also learned how to assess my own financial growth and future wealth within this turbulent market. These current books have played a major role in my development. They have helped me answer questions, and give solutions on social development and economic hardships of race and class instead of just asking questions!

MG: Over the years, I have noticed your portraiture’s environment evolve from more abstracted orbs of luxury goods to abstracted cityscapes and suburbs. Can you talk about this evolution?

IJP: Early in my practice before getting accepted to graduate school at Pratt Institute, I painted various designer clothes and brands on canvases using the trompe l’oeil technique. At this stage, I used my own clothing for the material. In doing so, I wanted to reflect the social construct of the perceived value of materials/brand power on the canvas. My aim was to help people in my community understand the value of an artwork. Many people in the Black and brown community do not see the powerhouse of an asset artwork has on your financial portfolio. I choose to define and open people’s eyes to this element. I thought if I painted a hyper-realistic “LV bag” for instance, on canvas, then people would perceive this artwork with value. If you like the clothes and bags so much, why not buy the canvas with the item on it? You will help propel the artist, and create a new brand simultaneously while buying an asset that increases in value instead of a decrease in value after you put the item on. This idea had substance before I went to graduate school. Upon arrival to graduate school, I later realized my community had changed, and everybody knew why art was valuable. So, there was no need for that visual concept. I had to generate other ways to apply concepts with circumstance. How do I show class, value, and hierarchical systems of social development? I just went to another asset class, structures/ real estate, and the evolution started to take shape.

MG: I know you are a jack of many trades, including residential renovation. How does the work you do with your family inform your practice? As an outsider looking in, it appears that you are “practicing what you preach” quite literally. Not inferring that your work is preachy at all. I think some lessons and conversations are prompted and pursued by those with interest.

JP: The work I do with my family plays an essential role in my practice. My father likes to say, “practice what you preach.” I find that relation integral to creating informed and truthful work. I talk about Black wealth, family, economic development, and maintaining assets in our community. My paintings ring with this environment, so shouldn’t I participate in the practice to make it authentic and truthful? I think so!