In 2010, artist Jeffrey Gibson cut the canvas of his paintings off their stretchers, shoved them into a garbage bag, dragged them down to his local laundromat in Brooklyn, and threw them into the washing machine. When I learned this, my first thought—after horror—was: why? My second thought was, did he put it on the "heavy load" setting? That second question we may never know the answer to, but that compulsion of Gibson's was the beginning of a new era of his work. One that embraced the "making" aspect of creation. And today, the fruits of the queer indigenous artist's impulsive decision are on display over at the Seattle Art Museum, at his show Like a Hammer.

Gibson, who's a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and is half Cherokee, fully embraces the idea of being a "maker." It doesn't have the constraints that weaving, painting, sculpting, filming, adorning, shooting have. “Make,” a word that means to “to bring something into existence,” is ambiguous, fluid enough to encompass the various work that Gibson does, from punching bags to paintings, sculpting to dancing, beading to stitching, honoring the kind of artistic work done in indigenous cultures as well. This distinction is especially important within a field intent on sidelining work that seems to fall into the craft category.

You'll also notice that a large portion of his work contains lyrics from songs that he grew up listening to (keep your eyes peeled for a James Baldwin quote!). Gibson frequently combines and layers pop culture with traditional methods, addressing the supposed impossibility of them both being together. During his time working at The Field Museum in Chicago while he was in school, indigenous work often wouldn't be shown that was deemed too modern to be considered a "real authentic artifact." These were the pieces Gibson felt represented him the most. And so his practice is largely informed by the "in-betweenness" of the fixed points of identity. And there it blossoms.

"Burn For You"

There are several of these genderless medium-sized figures throughout the show. They are made of wool that's been stitched together from blankets and stuffed with the recycled ragstock and sandbags from the insides of punching bags. The figures are then placed inside a rawhide suit with a rod stuck in the back that gives them the ability to stand up.

"Burn For You"—which I'm pretty sure is named after the John Farnham song—is covered in tin cones, or jingles, which come from Jingle Dance dresses that are worn during powwow. They were originally made of rolled tobacco and snuff lids but were then adopted by powwow dancers to put on their clothes; when moved they make a tinny sound. Now, these jingles are mass-produced in Taiwan by the millions with the explicit purpose to be used in powwows. The figure is also adorned with red nylon fringe and beads, which come from powwow regalia, with a crystal placed in the center of where the figure's face should be.

Gibson combined these traditional materials with an aesthetic that could also fit in with the club kid scene. The artist cited Leigh Bowery, a performance artist from the 1980s who established iconic club night Taboo in London, and Commes des Garçons as major influences in the shaping and fashioning of these figures. My first association, however was to the nkisi nkondi, a power figure from the Kongo people. Made of wood and carved in the likeness of a human, the figure houses a spirit. Nails and pegs were driven into them to activate the spirit inside to defend the righteous and destroy evildoers. Gibson's own medium-sized figures activated me in the same way—but less about good and evil, and more about whether the cheap H&M dress was really something I should be wearing. I think I understand what it was trying to tell me.

"ALL FOR ONE, ONE FOR ALL"

Two large figures occupy the middle galleries of the exhibition. Coming to Gibson in a series of dreams that lasted for two months, the same female figure would visit him, taking him to another plane where they traveled together. This figure would never show him her face and had a very pushy vibe. He took it as a lesson. “I was asking for sympathy and she refused to give it to me," he told us. "And she was basically telling me that I didn’t need it. That I had everything that I needed.” The sentence beaded on the back of her cloak, underneath all that nylon fringe says "ALL FOR ONE, ONE FOR ALL." She represents community.

When I saw the press photos before the exhibition, I was sure that the heads were made of those luchador masks—boy was I wrong. The heads are in fact his take on Mississippian effigy pots, made of high-fire ceramic with the glaze forever caught mid-drip down the side. There are holes where the eyes and mouth should be, melting in a way that looks like complete agony—the history of pain and conflict inflicted upon indigenous bodies apparent. The main body is held up by tipi poles, with a log from the Hudson River supporting it. The figure almost seems to be dragging itself out from something—dreams maybe. Or perhaps the river.

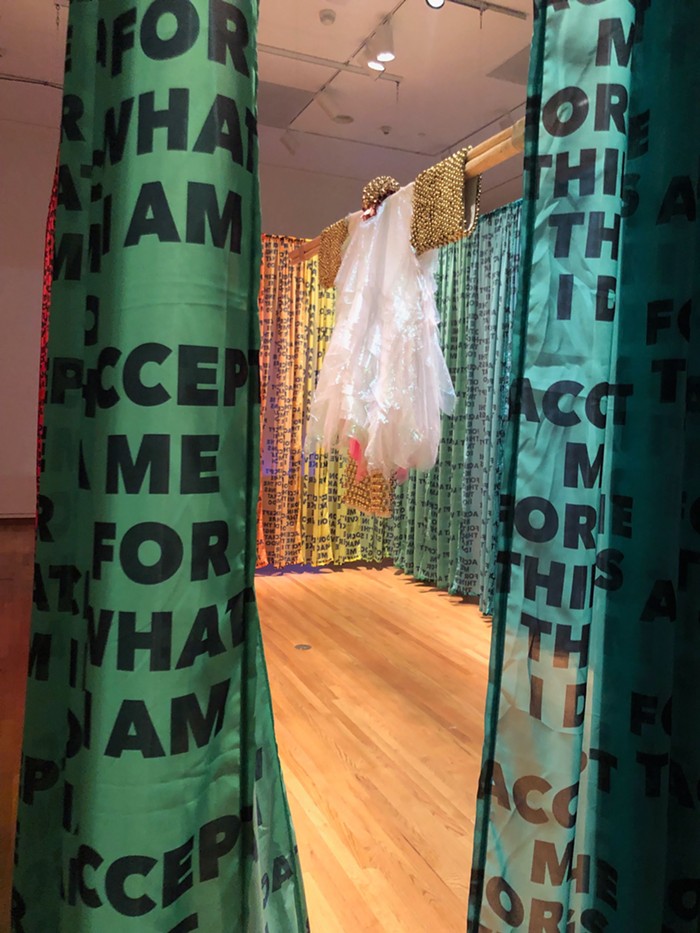

"DON'T MAKE ME OVER"

This piece occupies a small gallery in the back of the exhibition—the show's ending point. It's composed of rainbow colored fabric panels that come together to create a kind of room that flutters in the breeze our bodies create in the space. The panels—which are covered in lyrics from Dionne Warwick's iconic 1962 song "Don't Make Me Over"—conceal an iridescent dress made of chiffon organza and thousands of bells that's hung from two tipi poles in the middle of this makeshift room. A video of Gibson dancing, singing, and playing instruments while wearing the dress in the space is projected onto one of the walls.

The garment itself is transformative. Covered in thousands of bells that ring at the slightest of movements, his presence while wearing this dress is literally impossible to silence. Society often doesn't know how to accept queer indigenous men, but Gibson can move however he pleases in "DONT MAKE ME OVER." It's a performance and existence that the audience is not privy to. It can only be glimpsed through a slit in the corner of the space or seen through a video after the fact.

Gibson's Like a Hammer feels overwhelming in the moment. There are so many things! Art talks, and Gibson's work includes many voices speaking all at once, through song lyrics, materials, videos, sounds, colors. If you listen to all of them, you'll feel like you're inside of Gibson's head. It's a vibrant place to be.

Like a Hammer is at the Seattle Art Museum through May 12.