Miya Ando dips her paintbrush into a can of varnish, presses it against the edge to release excess, then oh-so-gently skims the bristles over a large block of charred redwood, carefully avoiding drips as she slowly rotates the wood. It’s sweltering and noisy outside her Queens, NY, studio on this summer day, but peaceful and cool inside. Ando hands me a brush and instructs me how to assist: with reverence. She tells me about her art as we work, like letting me in on a brilliant secret. “Wood graining is beautiful because it’s a recording of the age and the history of the material,” she says. “Each line shows you what it’s been through.” After we prep the blocks, a portion of each will be delicately coated with silver nitrate, which, she explains, will accentuate the grain by adding shimmering reflections to the striations and invite the viewer to ponder on the melding of disparate materials. The completed project is one of several of her pieces on view until March 29, 2020, at the Asia Society Texas Center in Houston.

The exhibition, “Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form,” is her response to the center’s architecture, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi. A principal theme throughout Ando’s work is time. She mixes natural materials — such as wood, metal and stone — in new ways to evoke the ever-changing nature of the world. This old-growth redwood is especially precious to her not only because it is a visible chronology, but also because it was sourced from naturally fallen trees from a forest on the other side of the country, in Santa Cruz, California, where she grew up. Thus it represents some of the earliest rings that make up her own life.

“I grew up on 25 acres of trees hundreds of years old, 300 feet tall,” she says. “They’ve seen it all.” Ando describes a childhood which alternated between being growing up in Northern California’s coastal forest and spending time in a Buddhist temple in Japan, where she learned about Buddhism from her grandfather, who was a priest. All of these facets of her personal history shape her aesthetic. “I incorporate my spiritual views into my practice,” she says. “Everything came from nothing, and everything goes back to nothing,” she explains, referring to her Buddhist philosophy. “It’s very egalitarian. Every single day, we all share that. I hope to make things that are a respite for people’s minds, and a contemplative environment that contributes to tranquility.”

This focus on temporality and tranquility can be seen in Ando’s response to Taniguchi’s building. The exhibition title, “Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form” derives from The Heart Sutra, a key text in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. In it, the Two Truths doctrine puts forth the concept that all parts of the universe are constantly in flux, and that nothing has a static state.

In the series Tides (Shou Sugi Ban), 2019, five redwood panels each with varying levels of silver nitrate, symbolize how the forces of gravity and planetary rotation affect water on Earth. The glimmering silver reflects a multiplicity of colors in the space as people pass, complementing both the architecture and the deep black of the charred wood.

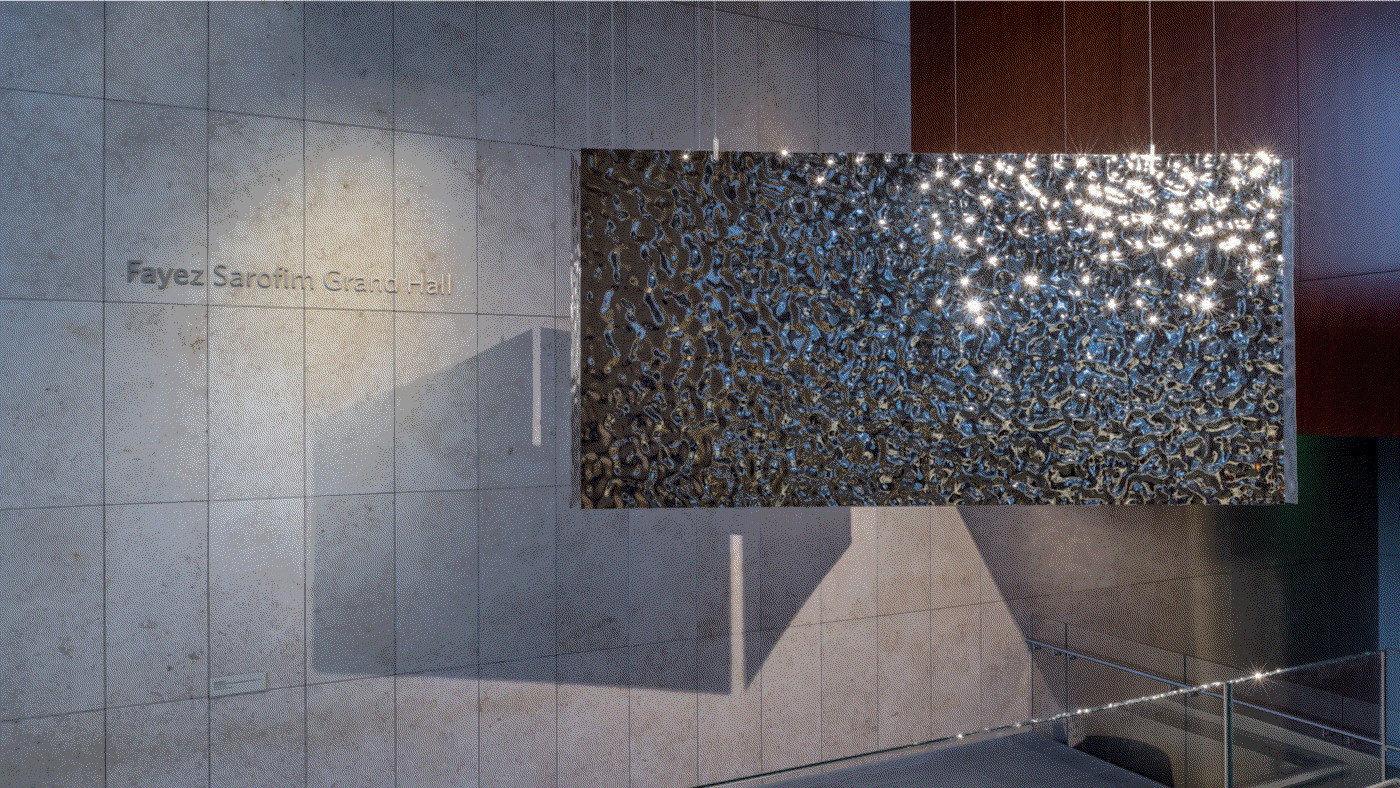

Mizukagami (The shadow of the moon reflected in water), 2019, are four large sheets of hammered stainless steel suspended from the ceiling, it’s surface reflecting light like ripples in water. As viewers walk past, the light refracts differently, emphasizing how perspective constantly shifts perception. Although the piece is made from strong industrial steel, its lightness of form and beauty gives one a sense of ethereal liquid. Ando is known for the original ways she manipulates and masters metal and loves working with paradox in the medium. “My ethos is a harmonizing of things that may not from initial perception have both qualities — delicate and hard, I’m interested in juxtaposition and perception” she explains.

The silver-black wooden cubes I assisted her with were studies for the work titled Ryōanji, 2019. The 15 blocks represent the Zen rock garden at the Ryōanji temple in Kyoto, Japan. The wood, in a state far from its original, was altered using a Japanese technique called shou sugi ban or yakisugi, which includes intentional charring and preserving. Ando explains: “I’m interested in elements and the combination of elements which become a kind of venn diagram — the work is neither silver nor wood, but something right in the middle. Not A nor B, but C. C is a place I like to traverse and investigate.”

Lastly, in Obon (Lee Ufan), 2019, phosphorescent stones comprise a rectangle, half inside the gallery, half out. Reminiscent of the Two Truths doctrine in their ever-changing glow, the stones were selected to reference the Japanese Obon Festival. Traditionally, people set glowing lanterns on the river to honor and guide their ancestors’ spirits at the festival’s conclusion.

In talking about how her Japanese heritage shapes her artistic outlook, Ando uses the example of conceptions of the galaxy. “In the English language we have the words “Milky Way.” In Japanese we have “the Silver River in Heaven” to describe the same concept. I prefer a Silver River because it makes you ponder. Whoa, there’s a river in the sky? And we are floating in it! How poetic, how interesting . . . that we are part of a tremendous, enormous river in space. I love the idea of the milky way being a river in the sky.” Ando’s innovative and contemplative exhibition at the Asia Society Texas Center in Houston pays homage to her lineage and the philosophy passed down through it. While personal, the works invite every single viewer to wonder. “For me, art is a dialogue,” Ando says. “It is not a soliloquy. I am saying something in the form of a visual object, but then the viewer comes and brings their own experiences and histories that they’ve accumulated in their encounters with the world. And they have a dialogue with that work. It occurs silently. It’s just this quiet, beautiful dialogue.”