A potent, urgent exhibition by Toronto-based multimedia artist Esmaa Mohamoud brings Black bodies into the white cube. To Play in the Face of Certain Defeat, on view at the Winnipeg Art Gallery until Oct. 16, challenges the historical invisibility of Blackness within institutional spaces by taking up room, physically and conceptually.

Mohamoud’s large-scale photos and big-impact sculptural pieces reference the visual iconography of sports, making for an accessible, immediate first impression. Sit with these works for a while, though, and they slowly unpack, revealing layers of charged and difficult meaning around class, gender, race and representation.

Mohamoud sees the seductive allure of athletics – she’s a sports fan herself – but she weaponizes it. The 29-year-old African Canadian artist, born in London, Ont., positions professional sports as a corporate extension of slavery in which the labour of competitive violence and performative masculinity is turned into entertainment.

Esmaa Mohamoud, One of the Boys (Black and White), 2019. Archival pigment prints, installation view at Museum London, 2019 (courtesy the artist)

The most striking works combine sports uniforms with ballgowns, mixing the conventional signifiers of male and female. One of the Boys consists of a series of large, vivid photographs, as well as two life-size, three-dimensional headless figures that are dressed in black and white. In the photos, Mohamoud starts with the intense colours and catchy team logos of basketball jerseys but morphs them into evening wear. These jerseys-turned-corsets, along with trailing skirts and luxe satins and velvets, are worn by masculine-presenting Black models. Their faces are sometimes turned away slightly, but sometimes encounter us directly; their bodies are powerful; their hands are posed in graceful, sometimes delicately eroticized poses. Decking out athletic male bodies in feminine debutante finery is both playful and provocative, questioning the confines of gender and sexuality, and the ways organized sports can reinforce and reduce them.

Esmaa Mohamoud, Glorious Bones, 2018-19. 46 repurposed football helmets, textiles, recycled tires and steel stands, installation view at Art Gallery of Hamilton, 2021 (courtesy the artist)

Mohamoud also repurposes sports equipment for subversive effect. In Chain Gang, a silver chain that runs taut from the floor to the ceiling is hung with sleek, silver-and-black Nike cleats, referencing the consumerist cachet of superstar athletes but also the shackles of prison work gangs. In Glorious Bones, football helmets are covered with African wax-print fabric and set atop black poles. The textiles are exuberantly beautiful, but the empty helmets feel ominous, evoking the toll contact sports can take on the body, particularly the head injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy associated with football.

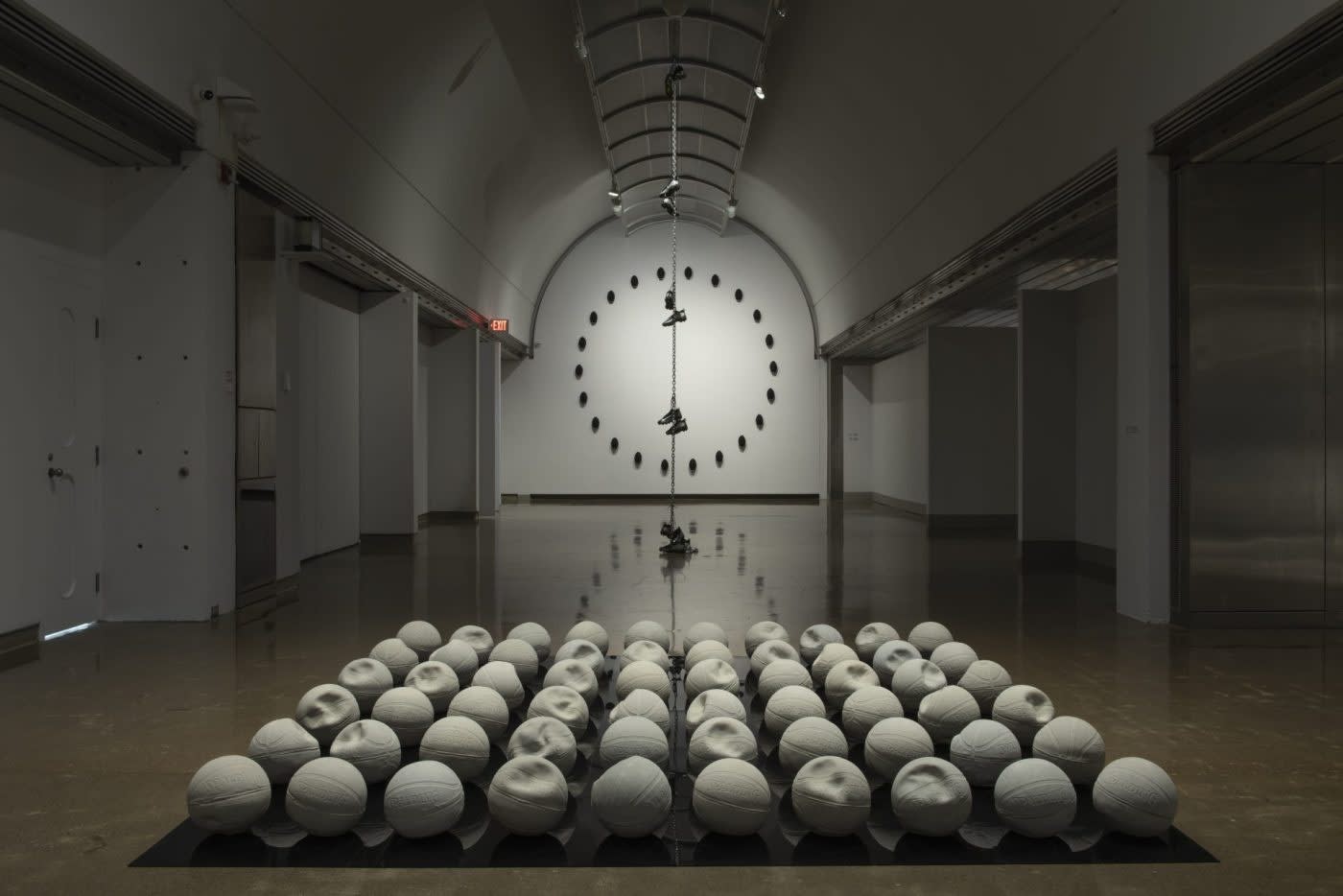

Esmaa Mohamoud, Heavy, Heavy (Hoop Dreams), 2016-19. 60 concrete basketballs and black acrylic, installation view at Museum London, 2019 (courtesy the artist)

In Heavy, Heavy (Hoop Dreams), what looks like dozens of dented, deflated Spalding basketballs rest on a surface that resembles a deep black reflecting pond. The chalk-coloured balls are cast in concrete, though, and are dead and weighty. Through this materiality, Mohamoud toys with illusion and reality, suggesting that pro sports, which seem like a promise of wealth and success for many young Black men, are actually an impossible mirage, a form of cruel hope.

Esmaa Mohamoud, Anything and Everything, Except Me, 2019. Vinyl text, installation view at Museum London, 2019 (courtesy the artist)

Paradoxically, one of the most crucial pieces in the exhibition is, at least initially, the hardest to see. Anything and Everything, Except Me is based on a quotation from Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me…. When they approach me, they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.” These words are placed on the floor near the gallery entrance in super-subtle reflective vinyl letters that likewise flicker between visibility and invisibility, depending on angle, light and maybe even viewer perception.

It’s a visual trick that’s also a perfect metaphor for Mohamoud’s transformative art.