Deborah Kass, artist, rebel, and raconteur, will be honored at the Jewish Museum’s 31st Annual Purim Ball at the Park Avenue Armory on February 22. Known for her mixed media, genre-blending interplay on visuals and language, Kass is not afraid of pointed social commentary. This bravery makes her work compelling, relevant, and uniquely urgent as a pioneer in the field of intersectionality. Her significance has been recognized accordingly with induction into the New York Foundation for the Arts Hall of Fame and inclusion in major museum collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Portrait Gallery, Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Modern Art, and the Jewish Museum. Her retrospective Deborah Kass: Before And Happily Ever After, was featured at The Andy Warhol Museum in 2012.

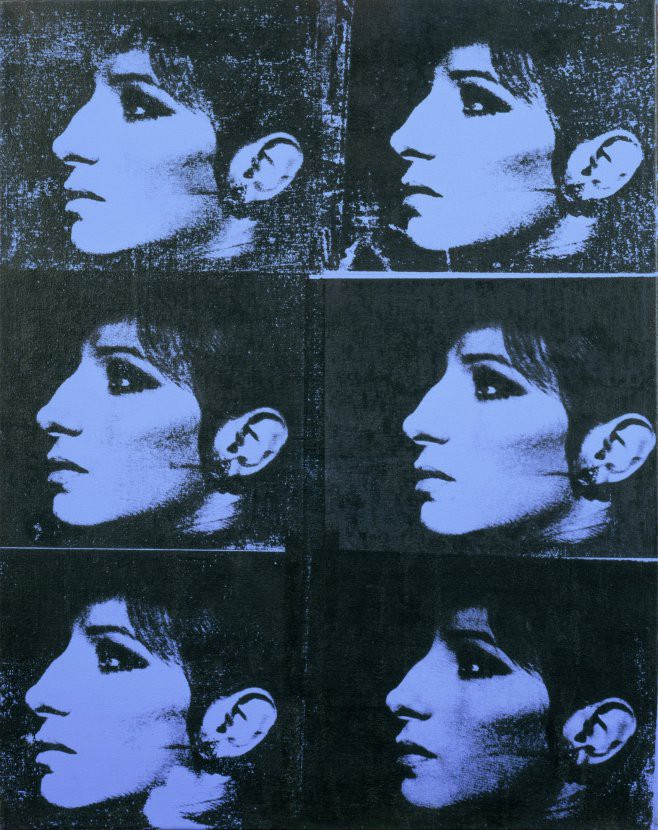

Deborah Kass, Six Blue Barbras (The Jewish Jackie Series), 1992. Screenprint and acrylic on canvas. 30 1/2 × 24 × 1 1/2 in. The Jewish Museum, New York. Gift of Seth Cohen, 2004–10

Among the artist’s work in the Jewish Museum collection include Six Blue Barbras (The Jewish Jackie Series) and Double Red Yentl Split (My Elvis), which examine her fascination with Barbra Streisand as an icon of Jewish womanhood. Exhibitions at the Jewish Museum which have featured her work include Too Jewish? Challenging Traditional Identities (1996); Art, Image and Warhol Connections (2008); and Shifting the Gaze: Painting and Feminism (2010), Her latest triumph, the OY/YO sculpture in Brooklyn Bridge Park, offered yet another example of her brilliant interplay with images and words. Kass’s “VOTE HILLARY” portrait of Donald Trump, an official fundraising print for the Hillary Clinton campaign, was featured on the cover of New York Magazine after the 2016 U.S. Presidential election.

Fierce, feisty, and as funny in person as her art is witty and provocative, Kass invited the Jewish Museum to her Brooklyn studio on the occasion of the Jewish Museum’s Purim Ball for a chat to reflect on her life and career. As she once told The New York Times, Kass is a “total, absolute, 100 percent provincial New Yorker” and celebrates her swagger with passionate opinions and unbridled sass. Her relationship with the Jewish Museum goes back more than twenty years, and a celebration of her body of work seems entirely appropriate for a woman who declared: “I wish we all had more Jewtude!”

When did you begin to identify as an artist?

I identified as an artist as young as four or five years old (Kass was born in 1952). I don’t even know where I got the idea. Most artists decide they are artists really young, but have no idea why — unless you grow up in the art world, and your parents are artists or collectors and you want to be one too. That was certainly not the case for anyone I knew. Of my generation, there are a remarkable amount of artists that came from New York suburbs and just couldn’t wait to leave and move to New York City. I drew all the time like most young artists do.

What was your first experience of the Jewish Museum?

I was brought into the Jewish Museum by Norman Kleeblatt (the departing Susan and Elihu Rose Chief Curator). We met each other and found we were really kindred spirits. We were both on a search for how Jewishness fits into the idea of multiculturalism. It was in the early 90s, when thrilling intellectual work was going on: activism, ACT UP, queer, feminist, and Critical Race theories were brand new. This was what I was really involved with intellectually and aesthetically. When I met Norman, he was the first person I met who was also doing the same work as it could relate to Jewishness.

We were thinking about Jewishness within the context of post-modernism and identity politics, which thirty years ago was much more interesting. The children of my contemporaries went to college literally learning the intellectual framework being built back then, whereas people in my generation went to school learning the white male cannon: period. In literature and in art. My work addresses this generational intellectual dissonance.

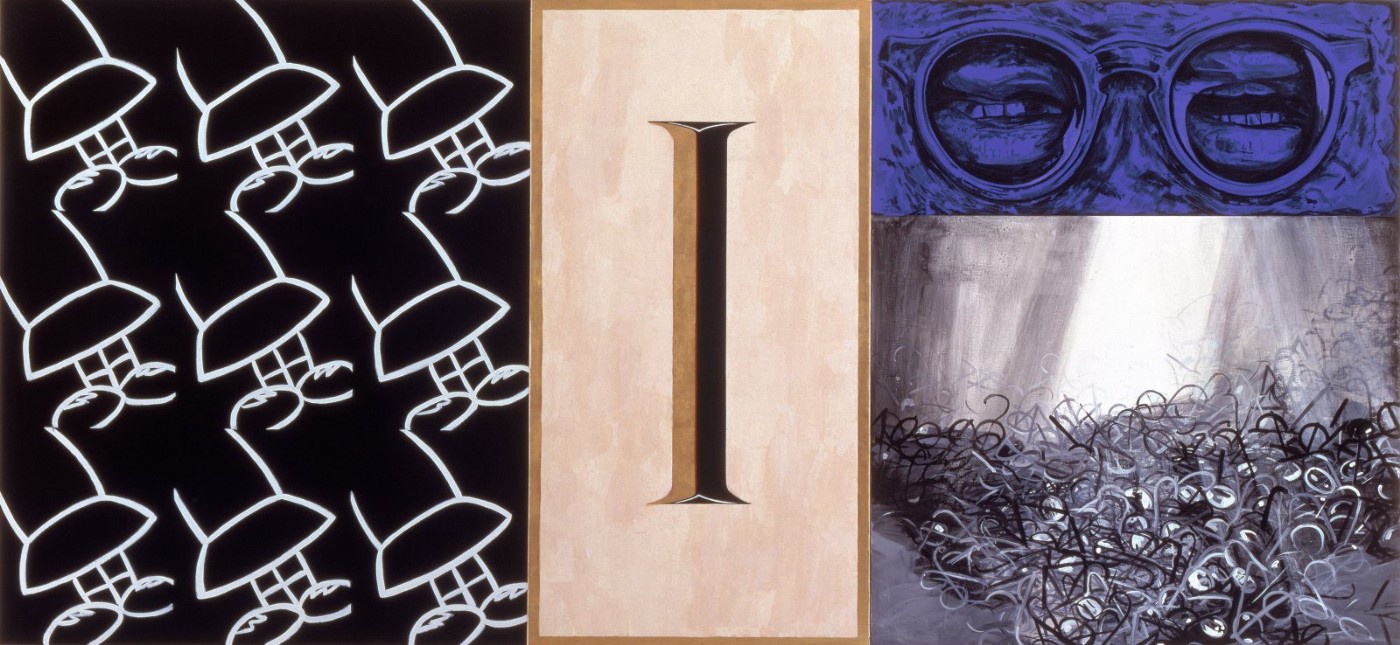

Deborah Kass, Double Red Yentl, Split (My Elvis), 1993. Screenprint and acrylic on canvas. 72 1/4 × 72 in. The Jewish Museum, New York. Purchase: Gift of Joan and Laurence Kleinman. 1993–120a-b

The image of Barbra Streisand figures prominently in your work. Particularly her image in Yentl, a movie she made based on a short story from Yiddish writer and Nobel Prize winner Issac Bashesvis Singer about a girl dressed as a boy so she can receive a Jewish education.

Seeing Barbra Streisand as a 13-year old from Long Island whose parents were from Queens, the Bronx, via Lower East Side, was very powerful. When she came on the scene, it was exactly the time I became aware of the outside world in a bigger way beyond the movies I had been watching and the music I listened to. When Barbra Streisand hit the scene, this girl was so radical and revolutionary. The way she looked, her pride, and her sense of self — she didn’t look like anybody I had seen in the movies of the 30–50s that replayed endlessly on TV late into the night. Barbra looked like people I knew, sounded like people I knew. Barbra didn’t change her name, didn’t change her nose. My friends’ older sisters were getting nose jobs at this point. That Barbra didn’t was a really big deal. And her sense of herself and of her difference as the source of glamour and power — being this proud Jewess was very radical.

What a fantastic role model for an ambitious young artist! She was revolutionary by virtue of simply being herself. When you identify a piece of the world and feel it has something to do with you, it is really a creative, pro-active experience. When you see your reflection in the world for the first time, it is life altering. Looking at Barbra, her unambivalent, glorious self-regard as a woman and a Jew, I realized I hadn’t seen anyone like her, like me, in popular culture before. That is major, and that is powerful. And that also points to work to be done.

Your social media presence speaks not only to your work, but also the work to be done. How do you feel about utilizing that space as a creative person, do you see yourself as a voice for radicalism?

I don’t know how many people would call me radical…. What’s radical and what’s radical enough is a qualitative judgement. Social media is simply an extension of my work — another kind of expression. Believe it or not, I’m pretty careful about what I post, even though I can be a prodigious post-er. I’ve made a point of not doing anything too personal. My topics are popular culture and politics. That is what I care about.

How did OY/YO come about?

I was at the Museum of Modern Art, saw Ed Ruscha’s OOF, and my brain just said “OY!” and I painted it. Then my friend said, “Oh look, it says YO in the reflection.” I learned quite a bit about creativity from Andy Warhol, how you make things, and how to spin ideas out. I turned to my friend, as Andy would have, and asked: Should I paint that? And she said, “Yeah!” So, I painted YO! There’s an OY painting and a YO painting. It seemed obvious it should be a 3-D object so you could see both words at once. Then I got the extraordinary opportunity to make it monumental.

When the OY/YO sculpture was installed in Brooklyn Bridge Park I knew it was an instant icon. It was so big, so yellow. It looked like the love child of “I Love New York” and (Robert Indiana’s) “Love.” To me, it was also a mash up of art history (minimalism and pop) and intersectionality. It hit every note I ever wanted to hit in my work, on a level and scale I never anticipated. I was blown away. It was, in a word, bashert! (Yiddish for “meant to be.”)

It became the wedding destination photo for so many different communities in our city of immigrants and strivers. I saw African-American, Asian, Latino, and Indian wedding parties doing photo shoots constantly. It was a trip. I was never there without at least one professional wedding shoot. Schools, class photos — from kindergarten through grad school — community groups, Hillary Clinton campaigners, and Quinceañeras! I was there when there was a very carefully staged proposal! There was even a group of young Hasidic girls taking a photo there. I am quite sure it was the first time they had ever seen their reflections in a contemporary work of art.

What direction do you see the evolution of Jewish art and culture moving towards?

Hopefully pride and celebration. Historically, internalized ambivalence is a real feature of Jewish consciousness. When Norman’s exhibition Too Jewish? opened at the Jewish Museum it was a big deal and people freaked out about it. The exhibition was really controversial for older people who grew up during the trauma of World War II. I have thought about the reaction to Too Jewish and my work a lot over the years. I came to understand it was ambivalence born of fear — that they were taught by ancient and recent historical trauma that in order to survive you do not draw attention to yourself as a Jew. For post-war assimilating American Jews, being Jewish was an uncomfortable combination of both embarrassment and pride.

For many younger people that has simply not been part of their lived experience. They have a different, unambivalent relationship to Jewishness, but there are no guarantees that the safety they have experienced is permanent, as we are seeing with the increase in hate crimes against Jews, Muslims, African-Americans, immigrants, and women across the country.

That said, there is a new generation embracing their “Jewtude.”

They are the future.