With MORE feel good paintings for feel bad times, Deborah Kass continues her dialogue with postwar pop culture. She discusses appropriation, being Jewish, lesbian, and ever passionate about painting with art historian Irving Sandler.

In 1992, I first saw pictures of multiple heads of Barbra Streisand in a grid that pirated Andy Warhol’s self-portraits outrageously. What was I to make of them? They were by a Deborah Kass, a name new to me. I could have walked away but I didn’t. Why would a younger artist appropriate the master appropriator? It had to be an homage. But why Streisand?

Because Streisand was a pop star. And it made sense to portray her in the style of the most celebrated pop painter. But wasn’t Streisand’s image Kass’s surrogate self-portrait? The in-your-face portrait of Streisand had to be a feminist statement. It introduced womankind, both Streisand as subject and Kass as artist (and would-be Streisand) into a style dominated by men. But Warhol was a particular kind of man. He was gay. And so, I thought, most likely was Kass. And that would make Streisand a lesbian icon. She is also Jewish, perhaps Too Jewish (the title of a subsequent show at the Jewish Museum of which Kass was the poster “girl.”)

Yes, Kass’s pictures were homages—to Warhol, to Streisand, to Barbra as a stand-in for Deborah, to gay artists male and female, to Jews, to both popular low culture and elitist high art—to all of the above.

Kass went on from Warhol and Streisand to appropriate the styles of Stella, Kelly and other artists she admired and to introduce texts sampled from popular culture, like Sondheim’s lyrics. But above all, Kass’s canvases are an homage to the art of painting.

(Irving Sandler and Deborah Kass at her studio in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn.)

Irving Sandler

Let’s begin with appropriation. You appropriate not only other artists’ styles, but also popular phrases. How did that come about?

Deborah Kass

Language seemed like a natural progression from using Warhol, who is so familiar to everyone. The texts come from Broadway shows or The Great American Songbook, also colloquialisms I grew up with, and some Yiddish.

IS

Why have you looked to popular culture for your texts?

DK

Because I’ve been completely molded by popular culture, the best stuff in postwar America. I’m nostalgic for it, for the optimism and influence our pop culture had on the entire world.

IS

But your borrowings are also from contemporary art. Looking around your studio, there’s Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Ad Reinhardt. They are counter to the popular element.

DK

I don’t feel like they’re counter. They’re all products of postwar America, our golden age that I’m so interested in revisiting as a tourist. I don’t think of high/low figures so much as categories since Pop. To me, at the time, the answer to formalism was simply content. Pop started it all.

IS

In the ’50s, to appropriate was a real no-no. However, once you go from Duchamp to Jasper Johns to Warhol, appropriation becomes not only a common thing to do, but possibly the central way of working in the era we call postmodernism. Does the idea of appropriation raise any problems for you?

DK

In my house there was only one kind of great art and it was jazz. There was this idea of “standards”: we’d listen to how “Sassy” [Sarah Vaughan],“Dizzy” Gillespie, “Prez” [Lester Young], “Bird” [Charlie Parker], “Trane” [John Coltrane], “Lady Day” [Billie Holiday], or Frank Sinatra do the same tune, all differently. So I grew up thinking that interpretation was completely within the realm of being a great artist.

IS

In my day, there was high and there was low, and never the twain shall meet. Pop broke down that barrier between the two.

DK

My generation grew up in the ’60s with Pop and formalism, so combining them seemed normal. It was one big bunch of information coming at you, and you created what you wanted out of that.

IS

The whole idea of the avant-garde seemed to collapse.

DK

When I went to college in 1970 conceptual art was huge, so to paint was a big no-no. I knew about CalArts when it started. There was a big ad in the New York Times, and I wanted to go because it seemed like the mythic Black Mountain I had read so much about. Well, my parents… there was no way I was going to California. Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh was far enough. I don’t regret it now, but it killed me then. The Christmas of my freshman year ten of us and two teachers—one of whom I was sleeping with, of course—drove two vans out to CalArts to see Allan Kaprow, whom the other teacher had studied with. We thought we knew what was going on. We were reading Jack Burnham, Norman O. Brown, Carlos Castañeda, and Arthur Janov.

IS

When everything became possible in the ’70s, if you no longer could “make it new” in the modernist sense, you still could remake it new in the postmodernist sense.

DK

When I moved back to New York it was very clear to me that there was something new from a formalist point of view: a new, female subjectivity. It’s quite stunning to think about all the women who were painting in New York and all the men they’ve influenced. When you say Julian Schnabel, I think Joan Snyder. Ross Bleckner, I say Pat Steir. In Carroll Dunham, I see Elizabeth Murray.

Double Red Barbra, 1993, silkscreen, ink on canvas, diptych: 45 × 72 inches (each panel 45 × 36 inches).

IS

Let’s go back to content. The first works for which you became known are based on Warhol, but the subject is Barbra Streisand.

DK

The subject is me. (laughter_) I never know the difference between subject and content. Irving, really, this goes back to 1992. I should probably just pull something out of my archive to read to you. I’ll see if I can find something fairly articulate. (_Searches.) I’ll read you this from the winter of 1993, during my show of this work. Remember, it’s almost 20 years ago:

Barbra is the pop diva who changed my life as a Jewish girl growing up in suburban New York in the ‘60s. Her sense of herself, her ethnicity, glamour and her difference affirmed my own ambitions and identity. I identified with her completely. Andy and Barbra both stood outside mainstream America, she as a Jewish woman, he as a gay man. He subverted the macho myths of post-war US painting and invented Pop art. She gained control of her own Hollywood projects before any other female star and made the movie Yentl before queer theory ever hit a university. In my own work I replace Andy’s male homosexual desire with my own specificity, Jew love, female voice, and blatant lesbian diva worship.

IS

From the Streisand pictures you moved into a much more complex way of picture-making where you began to choose motifs from a variety of artists and incorporate their styles as a kind of collage.

DK

It was a solid ten years after I started the Warhol Project. The new work started in 2002.

IS

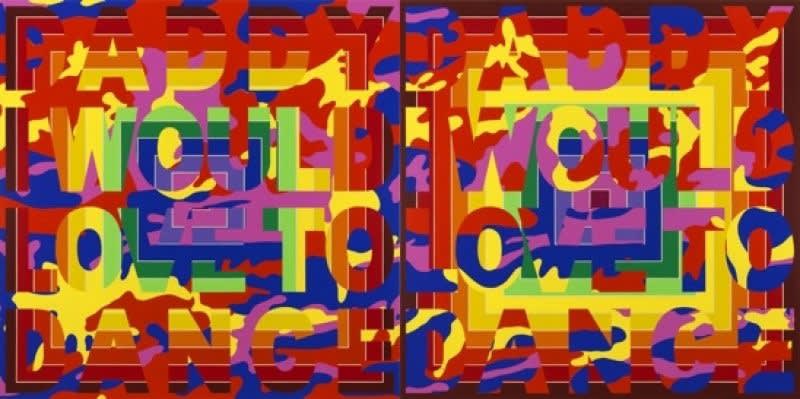

How do you choose which artists for which picture? In Frank’s Dilemma the camouflage comes from Andy’s camouflage paintings. Under the grid, and more or less concealed, are the concentric color images of Stella, and the text comes from where?

DK

The song “At The Ballet” from the musical A Chorus Line.

IS

Yes.

DK

The influence of Stella on me as a young artist was enormous––I saw his retrospective show at MoMA when I was in high school. I’d spent those years studying at the Arts Students League and prowling museums. Stella’s show convinced me I could be an artist because I understood what he was doing so clearly. Good thing, since I was already accepted at Carnegie. I have my diary from that day; I was sitting in the cafeteria of the sculpture garden, writing about the paintings and how the object itself, the supports, dictate the content coming in from the edges. I was so excited. I thought that if I could see the logic of each painting and the jumps between each new body of work, then I could actually do this with my life. He was utterly, profoundly important.

Desert Daddy, 2007, silkscreen, ink, and acrylic on canvas, 78 × 78 inches.

IS

You once mentioned that you wanted to find your way in between Stella and Warhol.

DK

I wondered how it was possible. Since college I’ve wanted to do a painting called Frank’s Dilemma. Decades later, I just came up with one. Ideas stir around forever. Later I wanted to figure out how to do something between Elizabeth Murray and Sherrie Levine. Or Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman.

IS

Does the text relate to Stella’s world?

DK

Well, Daddy I Would Love To Dance is the story of my life as an artist. It’s my absolute desire to participate—wanting to be part of history, wanting to talk to history, to dance with it. I’ve always seen art history as my community. In my mind these postwar artists are my friends. The line “Daddy I would love to dance” is the first female epiphany in A Chorus Line. The syntax is completely female. Little girls stood on their daddies’ feet and danced around the living room. That’s what the song is about, and that’s what me and art history is about.

IS

There is also your jazz experience and the idea in jazz of “covering.” Also, in current pop music the idea of “sampling” is so central and postmodernist.

DK

In the ’80s, I used the word sampling. I moved on to covering when I was covering Andy’s pop standards––Marilyn, Jackie, Liza, Liz––and interpreting them my own way.

IS

Point to what we’re talking about in the reproductions of pictures we’re looking at.

DK

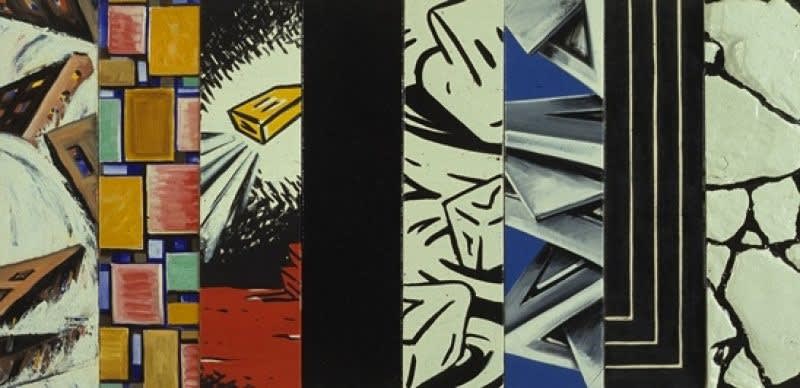

There’s sampling in this painting from 1989, titled Short Story II. The first panel is from an old landscape of mine, the first work I ever showed. Then, there’s a riff on ’20s and ’30s abstraction, which I love. Here’s Krazy Kat. This panel was actually a shiny, black stripe (paint with sand in it, I think.) That would be minimalism. Here are two more quotes from my earlier work. And then there’s, of course, Stella, and then Johns and Ashley Bickerton.

IS

In a way, you’ve moved from a collage of elements, which is more traditional, to a collage of different artists’ styles.

DK

My work changed when I realized that real life was not a gestalt. This realization came directly out of feminist, queer literary theory, and film criticism of the ’80s, along with critical theory on race. W. E. B. Du Bois’s “double consciousness of the oppressed,” for instance. The specificity of identity, all the multi-culti standards.

Short Story II, 1989, oil, acrylic, enamal, and molded plastic on canvas, 32 × 64 inches. Collection of Dan Cameron.

IS

What do you mean by gestalt?

DK

The idea of the unified picture plane. My life was certainly not a unified field, so that goal in a painting lost all interest to me. I’d spent my life trying to make a unified field, like Philip Guston, so that realization changed how I made a painting.

IS

When did you decide you wanted to be a painter, or an artist?

DK

For as long as I can remember, I wanted to be an artist. I have no idea where that came from; there was no interest whatsoever in my family or community. I thought being an artist was being a painter, but painting wasn’t cool when I went to school in the ’70s. Painting’s been dead since Duchamp––actually since 1906, when Cézanne died. That was the thinking then.

IS

The Russian Constructivists also claimed that they killed painting.

DK

It’s like saying the alphabet’s dead. Painting is just a medium. It’s what you do with it that matters. You don’t kill language because you don’t like what someone wrote. It’s food, it’s language, it doesn’t die, it just changes, and it’s to be used. To get hung up on the medium as the problem always seemed so dumb to me. It just seems limiting and silly. Bad thinking. Ultimately, with painters, it’s the pleasure principle that keeps us painting.

IS

But, at the same time, during your coming-of-age moment in the ’70s, you picked up on conceptual art, whose advocates proselytized strongly against painting. Aren’t you using language as a conceptual idea?

DK

Yeah. When I came to New York, painting was said to be dead, but so many people were painting: Elizabeth Murray, Pat Steir, Susan Rothenberg, Joan Snyder, and Mary Heilmann. The idea of being a painter looked great to me. Women were doing the best of it, and they were changing the subject in a way I recognized—it changed me totally.

IS

What was it in Murray’s painting that was important to you?

DK

When I saw Elizabeth Murray’s show at Paula Cooper in the mid-’70s the earth moved. I had been oblivious to feminism. In a proverbial thunderbolt moment, I realized that I and evidently everyone else assumed the subject position of all great art to be male. Suddenly, in her work, that all changed. The subject was female. And I mean “subject” as it came to be defined in the ’80s and ’90s—the speaking subject, the political subject. For the first time ever, I felt that I was the intended audience looking at a work of art. I saw my own reflection in a painting. This object had something to do with my experience of the world. In every sense of the word this was new. It was the intersection of New York School painting and feminism. I was never the same again.

IS

What was Carnegie like?

DK

Warhol went there [Carnegie-Mellon School of Art], so I went there. It was like most art schools in the early ’70s: total chaos. This is how crazy it was, here’s an actual assignment: our teacher got video cameras, and said, “We’re going to hitchhike to Lexington.” One of our coolest teachers, the one who had studied with Kaprow, was then in Lexington. We were stoned, we were tripping, and we had video cameras. We went from Pittsburgh to Lexington with our thumbs out on the road. A lot of those students would transfer to CalArts; a few people went to Denmark to do Primal Therapy. This was undergraduate school! I did a ton of acid, smoked a lot of pot. I was such a bad girl and, oh, I had the best time! I lived with my teacher for five years. It was my first serious relationship. If he was a woman, I’d probably still be with him. I learned everything I know about art from and with him—a lot of it tripping at the Carnegie, the Met, looking at Titian, Rembrandt, Cézanne, particularly Cézanne. It’s not a surprise I understood what Elizabeth was doing; we were coming from the exact same place, out of Cézanne.

IS

Then you came back to New York and entered the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program.

DK

It had been around for four or five years. I was in the Program when I was a junior. My father had just died a couple months before, so it was a traumatic time, to say the least. Basically they gave you a studio and you got to do your own thing. It was not rigid then; there was no over-riding agenda. We met with Philip Glass; Alan Shields, such a fantastically great hippy-dippy artist; and Barry Le Va…

IS

What were you doing then?

DK

Painting. Actually, I did an appropriated painting then, called Ophelia’s Death after Delacroix. It’s a copy of this eight-by-ten-inch Delacroix sketch that I made six feet by eight feet. I’ve had the appropriation urge for a long time; it’s who I am. I remember David Diao coming into the show of student work at the Whitney and literally hitting his head against the wall. He was so freaked out by this painting. That’s the first and last time I showed at the Whitney.

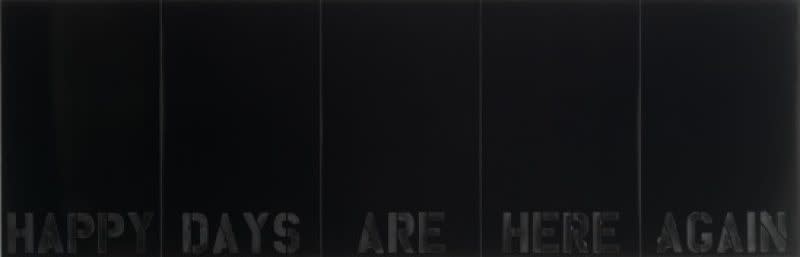

Happy Days, 2009, oil and enamel on linen, 26 × 80 inches.

IS

Talk about the impact of feminism. What was your initial attitude toward it?

DK

I didn’t think anything about the fact that there were no women in Janson’s History of Artor in my art history survey in college. I just assumed that, okay, there was Georgia O’Keeffe, there would be me. I didn’t even see it as an issue. Youth! I was not influenced by feminism because there were no women teachers, let alone feminists. Women’s studies had not been invented yet. And I didn’t go to CalArts.

IS

When did feminism become an issue for you?

DK

When the men in my generation started showing: Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Eric Fischl… There were simply no women painters getting any attention. I was so shocked by it. I thought feminism had cured the art world.

IS

It’s more complex than that. Elizabeth Murray was making ballsy pictures.

DK

She’s part of that generation that comes right before mine, the one that started showing in the ’70s. The economy changed in the ’80s and so did the art world. The guys my age were ready for it. I knew Julian from the Whitney Program and, man, was he ready! He blew my mind. The Pictures artists––Kruger, Levine, and Sherman––all of whose influence on my work cannot be overstated, were reacting against the mythology of the great male artist and originality. Painting was seen as embodying that. I was reacting against it too, but by making paintings about those same issues. There were feminist critics who believed painting to be so “overdetermined” that a woman shouldn’t even do it. Now, finally, over the next two years, I’m in a bunch of shows like the one at the Neuberger Museum entitled The Deconstructive Impulse: Women Artists Reconfigure the Signs of Power. It’s literally the first time a painter has been included in shows about appropriation. How can you talk about representation, value, power, and not take on painting? Yet at that time you couldn’t deconstruct painting politically, the way advertising and media were being deconstructed. The fact they wouldn’t bring those issues into painting was political and financial. Maybe that’s the answer.

IS

Yeah, but, on the other hand, you’re in somewhat of a contradiction here because these women painters did make an impact.

DK

Irving, they made their impact in a decade when people were looking for women. It was the ’70s, feminism’s second wave. Recessions and women artists always go together. I’m talking early ’80s and beyond, when the market shifted out of recession into the Dynasty days of Reaganomics. The highly visible painters were all men and they made fortunes. Women did photography, which was a marginal market then, which Sherman, Kruger, and Louise Lawler completely reinvigorated.

IS

Jump ahead. You now teach at Yale, and you teach women. What is the status of feminism today? What do your students think of it?

DK

I am at Yale as a Senior Critic. I go to studios. Since I have no class, there’s never a minion. I have some guilt about encouraging women there. It’s an entirely supportive atmosphere and I worry about what they will be facing when they enter the real world.

IS

You are a lesbian woman. Did that make any difference in your career?

DK

It was a bad business decision to not be attached to a man. I had no idea about the difference in money, security, and status, about how much all that matters in the art world. I was very naïve. Without a man, a woman, straight or gay, is vulnerable in ways I never could have imagined.

IS

Looking around the studio, I see that you’ve painted one of your most complex paintings, the one that refers to Warhol and Stella: Frank’s Dilemma. Many of these other recent paintings have become considerably more elemental. You appear to be looking to Ellsworth Kelly. The styles you appropriate are those of male artists.

DK

History is populated by men. When I was kid looking around MoMA, not seeing women didn’t stop me from falling in love with Cézanne or Guston or Kelly or Andy. All I can say is that I hope that my own subjectivity comes through. When I stopped being Andy and turned 50, I decided everything that comes next is icing on the cake, and that I could promiscuously indulge all my greatest loves—painting, language, politics, the American Songbook—and have serious fun.

Double Double Yentl (My Elvis), 1992, silkscreen and acrylic on canvas, two panels 72 × 72 inches each. Collection of Norton Family Foundation.

IS

How old do you think “old” is? You’re talking to a very ancient person.

DK

Well, I felt very old then. Now 50 seems young. I did a lot of drawings for a year and this body of work is what happened. It’s pretty old fashioned, really. Kelly has been part of my thinking for so long. The fields of flat gorgeous color in the new work are sheer pleasure—heaven to me.

IS

You were in the Too Jewish? show at the Jewish Museum in 1996.

DK

I was the poster girl, literally. That was something. The work in that show, My Elvis (1992-1997), The Jewish Jackie Series (1992), and Sandy Koufax (1995), addressed a missing part of the multicultural dialogue: Jewishness. Given the Holocaust, I find the omission alarming. Why this particular ethnicity is so problematic in the New York art world is a whole other interview. Being a famous Jewish artist affected my career more than being a lesbian, not in a good way. The things very important Jewish consultants and collectors said to me! Some were furious with me and they felt completely entitled to tell me. The self-hatred was astounding. It was the absolute antithesis of the pride that black collectors have about black artists. Who knew?

IS

Then you didn’t have a show in New York for what… 12 years? Why?

DK

Maybe that’s why. José Freire, my dealer, closed in 1995. He owns Team Gallery now. I had a couple of offers, but I felt I deserved a promotion. Despite the success of both of the Warhol shows, no next-level gallery asked.

IS

No way!

DK

Yes, way. When I negotiated a sale of Double Double Yentl (1992) to Peter Norton, I thought maybe I didn’t need a dealer for a while. Not being visible for so long may have been a mistake, but I didn’t want to show more Warhol work in New York. I wanted to wait until I had something new to show. If a great dealer had come along, I would have gone there, but a great dealer didn’t come along until Paul Kasmin in 2006.

IS

Have artists whose styles you’ve appropriated ever said anything to you about it?

DK

When I started with the Warhol work, Roberta Bernstein came into the studio and said, “Andy would have loved this.” When I met Robert Rosenblum, he said the exact same thing. God, I love art historians. Live artists are another story we don’t need to get into. Kelly owns a piece of mine, so I hope he is sympathetic. I’m just hoping that the live artists I love so much take the work as the compliment that it is.

IS

When is your next show scheduled?

DK

September.

IS

But the body of work is—

DK

I know, pretty much done. I’ve got a giant 21-foot painting coming and hopefully that probably will unleash some more.

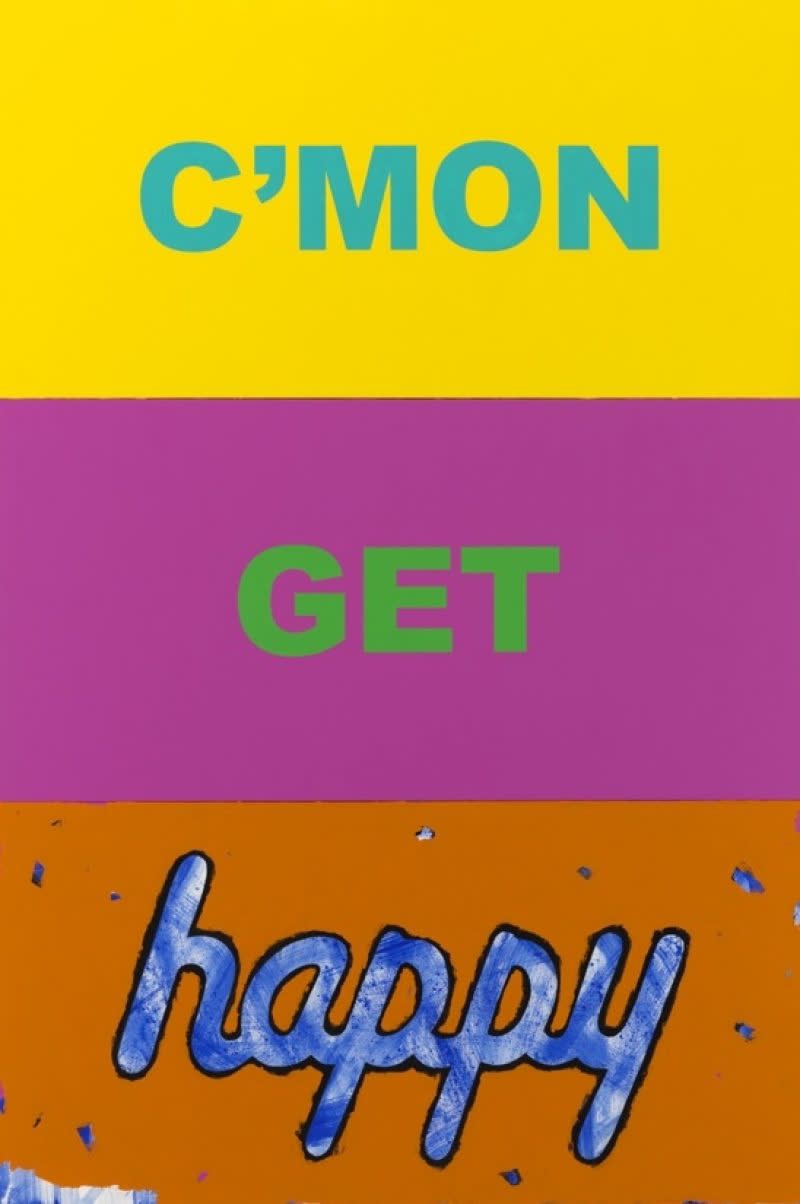

C'mon Get Happy, 2010, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 × 48 inches.

IS

You consider yourself a political artist?

DK

Yes.

IS

But your texts are not political.

DK

They can be read in a completely political way. Working with Warhol gave me an understanding of the relationship between seduction and subversion. In terms of politics, the paintings for the feel good paintings for feel bad times show came directly out of my loathing of the Bush administration. Every single word I used could be read both emotionally and politically. When I started, the first words I drew were “Sing Out Louise.” Everything is political, even that. Other titles are Nobody Puts Baby in the Corner, Let the Sun Shine In. Politics is utterly emotional, that’s clear. The new show is called MORE feel good paintings for feel bad times. This work is equally political but it’s much sadder. We’ve hired a new guy to fix the world, but it might not be fixable. The anxiety over the possibility of complete annihilation presents the ultimate existential dilemma. (Frank’s Dilemma ain’t nothing compared to that.) I guess that’s how the Abstract Expressionists felt after World War II, genocide, the atomic bomb, and during the cold war. Stunning to be in that same place now. Art should change to reflect it.

DK

At least two of these paintings will be Sondheim lyrics.

IS

Why Sondheim?

DK

He’s the last great Broadway composer and lyricist. This year he turned 80. Sondheim is looming very large. He’s sublime. No one deals with the complexities of modern life the way Sondheim does, with alienation, irony. This is what you do when you’re an artist; you talk about the human condition. I know it’s corny, but I hope these new paintings of mine do. If they do it by using other people’s words and other people’s styles, it’s fine with me.

IS

This is your personal take, the formative basis of your art.

DK

Part of the Sondheim attachment is to the despair. I don’t want to feel hopeless, but I do. The state of the world is beyond ironic. And the oil spill…

IS

Everything.

DK

I thought at 16, in 1968, the world was mine to change. I thought we changed it. God, were we wrong.

IS

We didn’t discuss the American dimension of your work.

DK

Not only American. (laughter) New York! It’s utterly provincial. It was the time when New York was the center of everything. It’s the nostalgia for the idea of greatness, for the ability to think and live ambitiously. The idea that you could change the world ends up looking so incredibly innocent. Even sweet.

IS

It does now, but it didn’t then, and it led to some great art being made.

DK

Yes. The suburbs were such an embarrassment to my generation. So bourgeois! All we wanted to do was be in New York and be intellectuals and make culture. At least I did.

IS

It wasn’t that different for my generation. It was more possibly out of necessity that we were bohemians.

DK

Oh, it was necessity. I lived on West Broadway for 25 years. I used to say, “Ah, West Broadway: the Boulevard of Broken Dreams.”

IS

We used to call it The Battle of West Broadway.

DK

Did you see Red? Did you like it?

IS

I did. As theater it’s wonderful; the acting is terrific. The rhetoric is dignified, somewhat over-dramatic and a touch pompous, but fair enough. I lived through the time of Red. I did eight interviews with Mark Rothko for a book on him I did. We met fairly frequently. Rothko would not have encountered the kind of young artist in the play in 1958; it’d be more likely in the mid-’60s or later.

DK

I’ve a hard time with the great man thing, in case you didn’t notice.

IS

Well, so did this young artist. The playwright really tracked down a huge amount of information. There was at least one thing that I thought only I knew.

DK

Really?

IS

At one point Rothko says to the young artist, “You’re fired.” The kid is really taken aback and says, “Why, why?” Rothko answers, “You’re too close to my generation. Stick with your generation.” This actually happened to Al Held. He and Mark had a pleasant lunch together, and after it was over Al said to Mark, “Let’s do this again.” Mark said, “No.” Al was crushed. Rothko then told Al what he says to the young man in the play. Al later said that Mark was right.

DK

These stories are so important, Irving. I am loving your memoir! Rothko freaked me out as a kid; I thought, There’s no way I’m ever going to be this spiritual.

IS

I didn’t think of his painting as spiritual. It struck me as existential. Is the spiritual reading too Jewish?

DK

Wow. You’re right; Rothko is definitely existential. My first love, Stella, was totally material.

IS

It took me time to appreciate Stella. When I first saw his black paintings I thought that if what he was doing was art, then everything I stood for had to be something else. I remember leaving a Stella lecture in 1960 with Robert Goldwater, a great art historian and my mentor, who was married to Louise Bourgeois. He turned to me and he said, “That man is not an artist, he’s a juvenile delinquent.” When agreed then. Warhol was beyond the pale of art. But I changed my mind.

Frank's Dilemma, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 78 × 159 inches.

DK

What about Johns?

IS

He was and is a beautiful painter, no doubt about that. But his subject—American flags, for instance—put us off back in the ’50s. His was often disparaged as neo-Dada, the new anti-art.

DK

I just saw that great flag painting by Johns at Acquavella Galleries uptown. I felt like I was looking at an animated Willem DeKooning that just kept changing. You could look at that painting forever and keep seeing new things. No way to see it all at once. Vivian Gornick hated the work. She basically called it “gay,” without using that word.

IS

I first ran into this kind of idea in Susan Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp’.” The term comes from gay argot and it implied that pop art was somehow a gay style.

DK

Another reason to use Andy.