-

Artworks

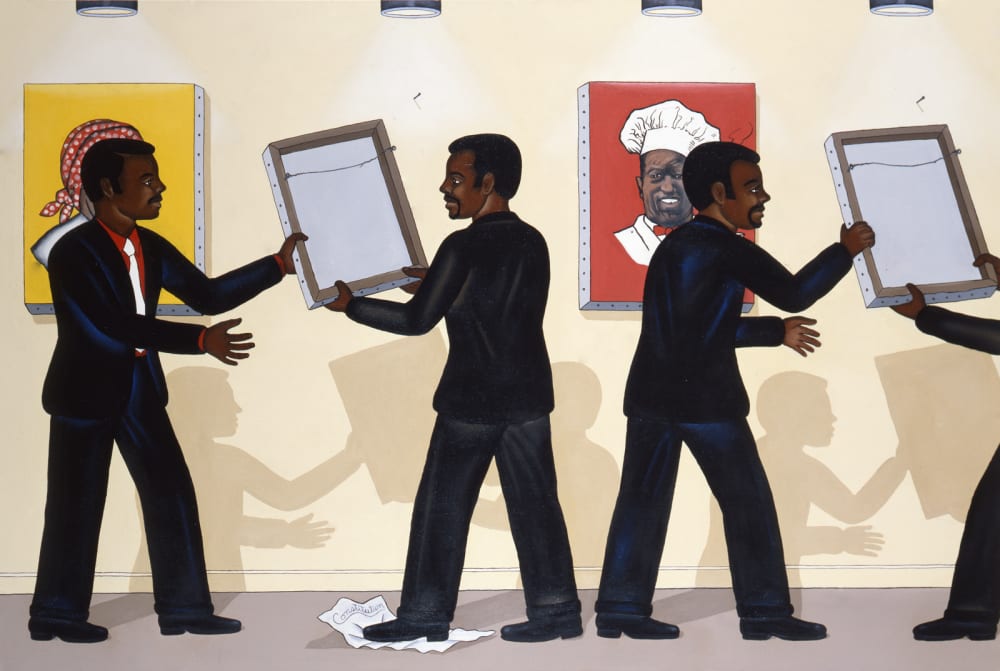

Roger Brown

Third World City Council Alderman Remove Pictures At An Exhibition Which They Find Offensive, 1988Oil on canvas48 x 72 x 2 in

121.9 x 182.9 x 5.1 cm7653Further images

Harold Washington was Chicago's first African American mayor, a major milestone that remains celebrated to this day. A polarizing figure known for his strong-arm political tactics, Washington's election in 1983...Harold Washington was Chicago's first African American mayor, a major milestone that remains celebrated to this day. A polarizing figure known for his strong-arm political tactics, Washington's election in 1983 saw major intracity political battles as various council members, aldermen, and other political figures were divided along lines with or against the new mayor. Washington regrettably died fairly young, only 65, just a few months after being elected to his second term in 1987.

A rumor circulated in the months following his death that doctors at Northwestern Memorial Hospital had found women's lingerie under Washington's suit when he had been brought to the coroner. David K. Nelson, a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) who primarily worked in satirical, iconoclastic figure painting, produced a painting based on the concept about six months later, in 1988. Titled Mirth & Girth, the painting was a full-body portrait of Washington in pink undergarments, including stockings and a garter belt, holding a pencil as per another rumor that he had died while reaching for a fallen pencil. The title was a reference to "Girth & Mirth," a club for overweight gay men.

On May 11, 1988, Mirth & Girth was displayed at a private exhibition in one of the school's main interior hallways. The painting was part of a set of six that Nelson was displaying in a judged three-day student fellowship exhibition held to showcase upcoming graduates. Within an hour of the show's opening, the painting drew negative criticism and the School began receiving angry phone calls and demands that the painting be removed. Within a single day, Alderman Bobby Rush put together a resolution threatening to cut all city funding to SAIC if they did not have the painting removed.

Leaving the Council meeting, the Aldermen went to SAIC to deliver the terms same-day. Aldermen Edward Jones and William C. Henry were the first aldermen to arrive from the City Council session. According to the federal lawsuit thereafter, Henry showed he had a gun, and then with Jones removed the now-hung painting from the wall and placed it on the floor, facing the wall. After they left, another student rehung the painting. Three other aldermen, Allan Streeter, Dorothy Tillman and Rush, arrived later. They took down the painting and attempted to remove it from the school, but were stopped by a school official. The aldermen then took the painting to the office of the school president Anthony Jones; at some point in the transpiring of the events, the painting's face received a five inch gash, likely slashed by one of the Aldermen.

Alderman Tillman threatened to burn the painting in President Jones' office, but a Chicago Police Department lieutenant present with the aldermen, Lt. Raymond Patterson, advised against this. Instead, another unnamed alderman called CPD superintendent Leroy Martin. Martin telephoned Patterson in Jones' office and ordered Patterson to take the painting into police custody, telling Jones that the painting amounted to "incitement to riot". Patterson overrode this direct order, citing his own powers as the lieutenant on the scene and hung up on Martin. A CPD sergeant accompanied Rush, Streeter and Tillman to a waiting police car with the wrapped painting in hand.

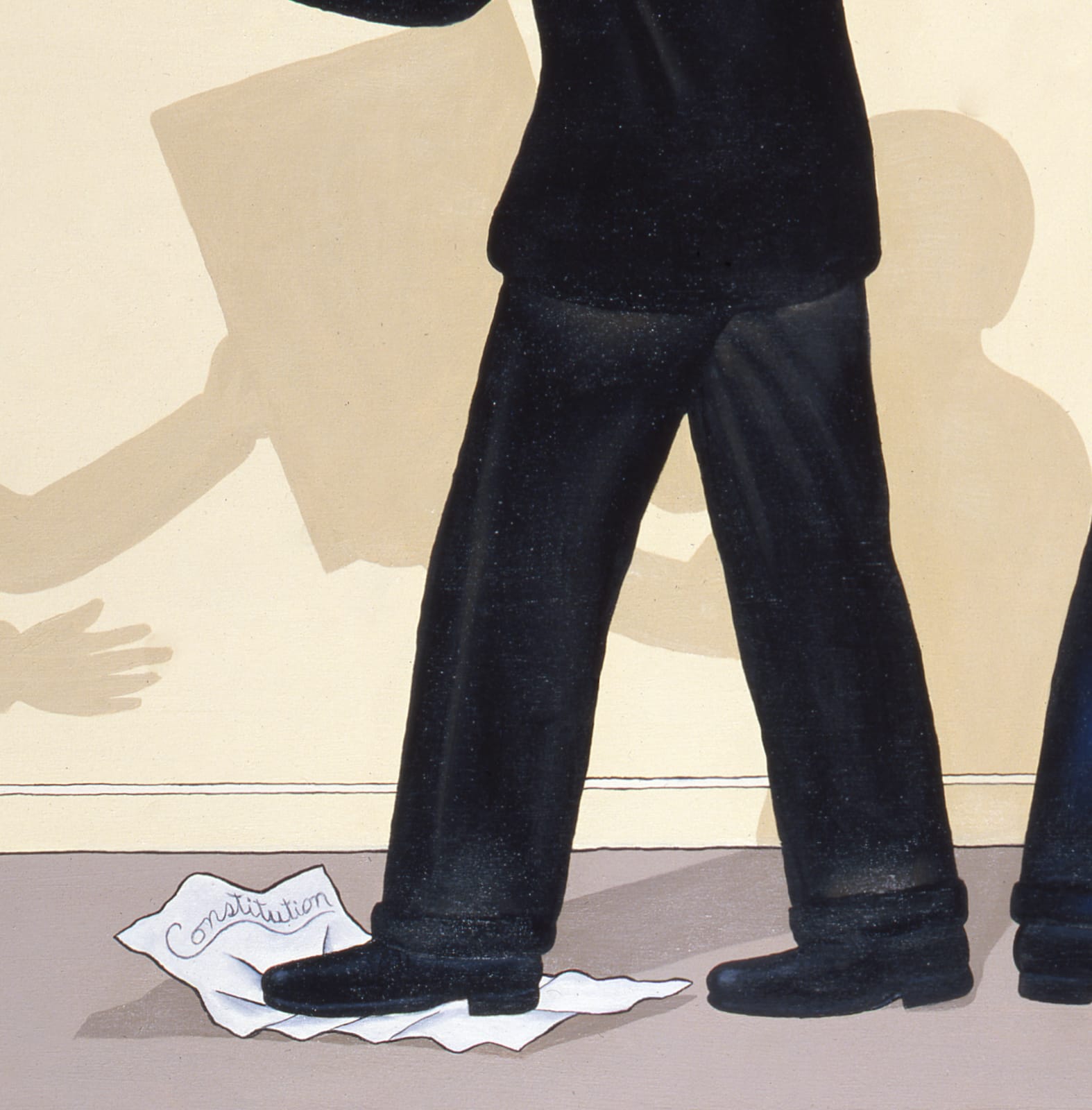

Nelson later sued the Aldermen with help of the ACLU. The suit claimed the removal of the painting violated Nelson's First Amendment right to freedom of expression, Fourth Amendment right to protection from unreasonable seizures, and Fourteenth amendment right against being deprived of property without a hearing. The suit would not be resolved for another six years, Nelson eventually settling the case in exchange for a pay out; the Aldermen, despite accruing several hundred thousand dollars in legal fees, marked the settlement as a victory, as they had not admitted on public record to any wrongdoing, and the criminal charges had been dropped.

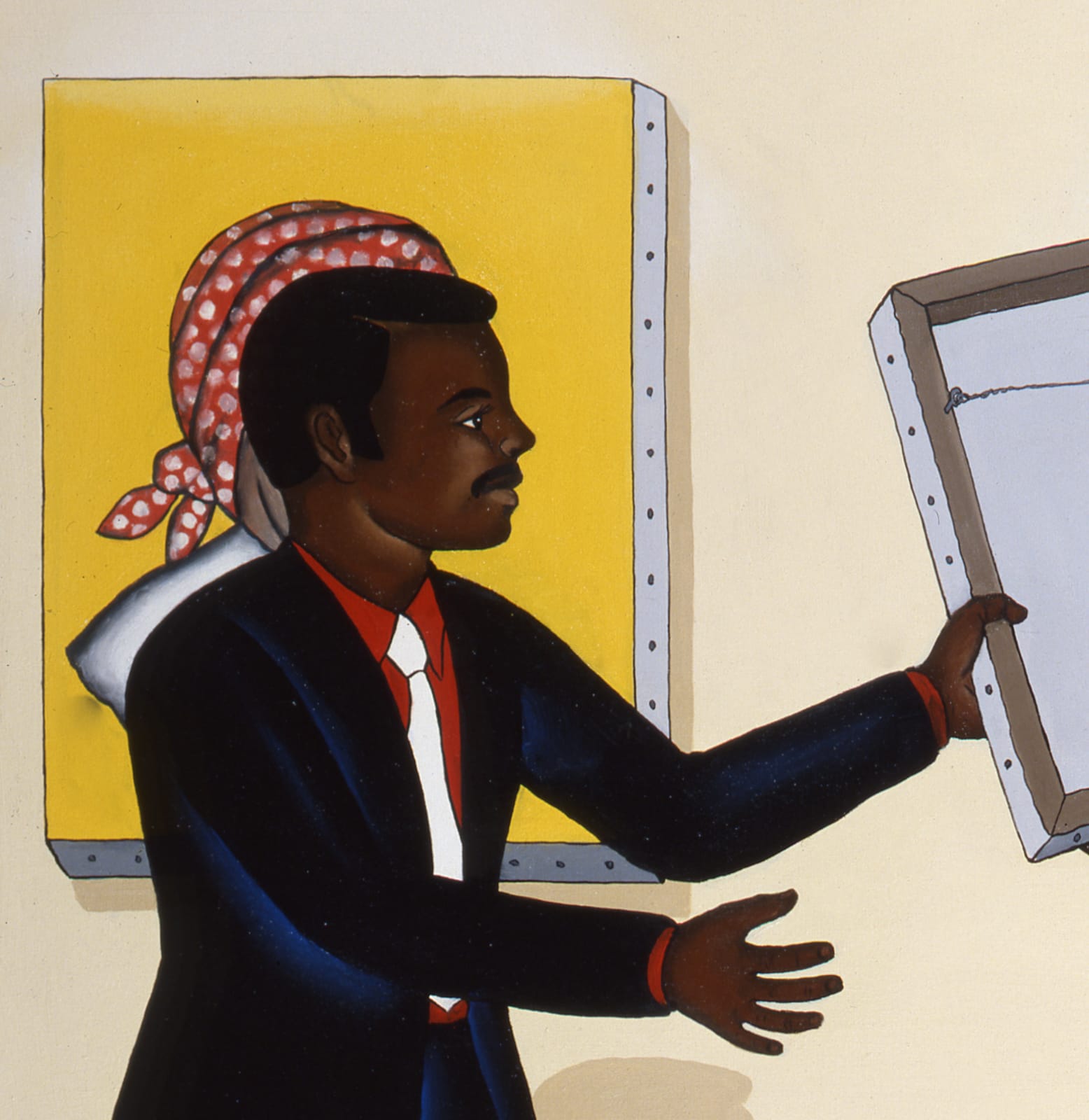

Roger Brown, greatly disturbed by the events that had transpired at his own alma mater, painted this theatrical approximately of the events the same year that they had transpired. Taking some artistic liberty by having four Aldermen moving two paintings, the rhythmic structure of the painting is as much or more Brown's own symbolic take on the situation, rather than a journalistic documentation of the specific event.2of 2